This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

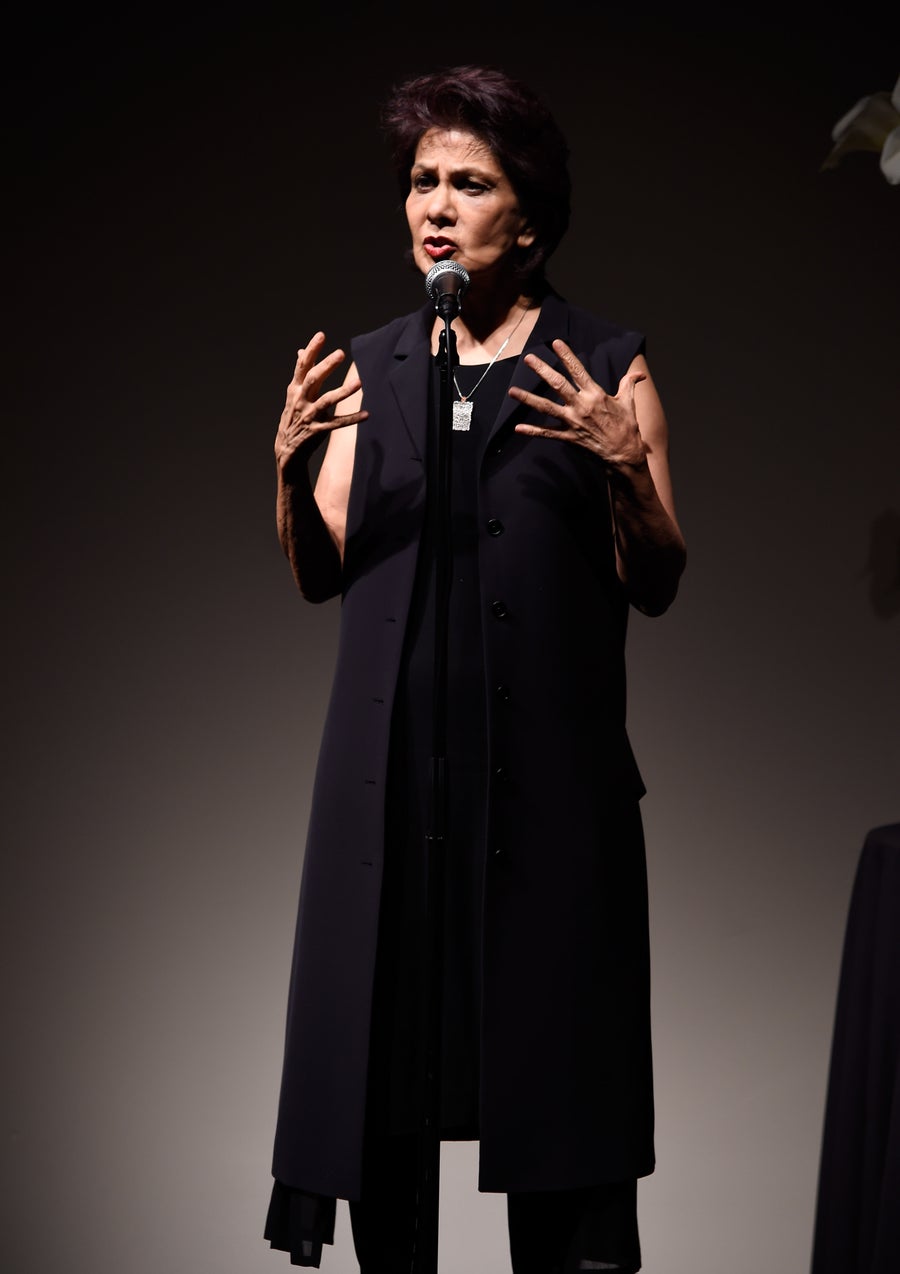

Azra Raza, an oncologist at Columbia, has watched too many people die from cancer. They include her patients and her husband, also a cancer specialist. She has poured her frustration into a new book, The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last.

“No one is winning the war on cancer,” Raza says. Claims of progress are “mostly hype, the same rhetoric from the same self-important voices for the past half century.” Her book details the excruciating suffering endured by her husband and others during largely futile treatment. She proposes a radical “new strategy” that switches from treating cancer to preventing it from occurring.

Oncologist Siddhartha Mukherjee, author of the 2010 bestseller The Emperor of All Maladies (which I wrote about here) calls First Cell a “powerfully written and far-reaching book that will change the conversation around cancer for decades to come.” I, too, admire Raza’s passion and eloquence, but I fear her “new strategy” would make a bad problem worse.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Raza is certainly right that cancer medicine needs reforming. As she says, it makes a mockery of the ancient physicians’ dictum, “First, do no harm.” Treatment of her specialty, acute myeloid leukemia, “has not evolved much in fifty years, nor has it for most of the common types of cancer. With minor variations, a protocol of surgery, chemotherapy and radiation—the slash-poison-burn approach to treating cancer—remains unchanged. It is an embarrassment.”

Raza excoriates research that tests potential cancer drugs on cultured cells and on mice and other animals, which are poor proxies for humans. Ninety-five percent of drugs that show promise in animal and in-vitro research fail in clinical trials, and the remaining five percent extend patients’ lives by a few months, “at best.”

Between 2004 and 2014, the FDA approved 72 new anticancer drugs, which prolong survival for an average of 2.1 months. As many as 70 percent of approved drugs turn out to be harmful. “How good are the solutions we offer,” Raza asks, “if we constantly have to ask ourselves whether the cancer or the treatment we prescribe will kill the patient?” Good question.

There are success stories, Raza acknowledges, especially when it comes to chronic myeloid leukemia, certain bone-marrow and lymphoid cancers and childhood cancers. But these are exceptions “among a litany of failures.” Immune therapies, which have generated excitement lately, “help very few patients” and cause “very severe side effects.” In as many as 30 percent of patients treated with immune therapies, tumors grow faster.

The American cancer industry touts drops in mortality over the past few decades. But according to Raza, the reductions stem primarily from the decline of smoking rather than advances in treatment. She points out in a recent Wall Street Journal essay that “overall cancer death rates are not dramatically different from what they were in the 1930s, before they rose along with cigarette use.”

Then there are surging costs. Cancer medicine has become a “monstrous business enterprise” in the U.S., Raza says. Bills totaled $125 billion in 2010 and are expected to rise to $156 billion next year. (Another recent paper cites a figure of $175 billion.) More than 40 percent of people diagnosed with cancer lose their life savings within two years, according to one study.

So what is Raza’s solution? Instead of treating cancer, she proposes, we should prevent it from occurring in the first place. That means detecting potentially cancerous cells early--really early, when they first emerge--and eradicating them before they spread. Under Raza’s plan, “everyone from birth to death is screened for the first appearance of cancer cells in the body.”

Ideally, devices implanted in us at birth would monitor our blood for cancer biomarkers and “send signals in a timely manner so that confirmation, validation and treatment could swiftly follow.” Researchers are already developing the technologies required to fulfill her vision, Raza says. “Liquid biopsies” plus big data and machine learning will “revolutionize the way we diagnose and prevent rather than treat cancer in the future.”

The problem with this scheme is that—as I’ve pointed out repeatedly--early detection doesn’t work. A 2015 review of screening methods for cancer and other diseases found that none extend life, when all causes of mortality are taken into account. Studies have revealed that mammograms and tests for prostate cancer have led to massive overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

Ironically, Siddhartha Mukherjee, whose praise runs across the cover of First Cell, has revealed the flaws with early detection and prevention. In a 2017 New Yorker article, “Cancer’s Invasion Equation,” Mukherjee points out that many healthy people harbor cancerous cells and tumors. Autopsies have revealed that people who die of other causes often had cancer in the breast, prostate and thyroid. For reasons that are poorly understood, cancer cells only overcome the immune system and become life-threatening in certain people at certain times.

This means that many people who test positive for cancer get treatment that they don’t need. For every man whose life is saved by a test for prostate cancer, from 30 to 100 men receive unnecessary surgery, radiation and chemotherapy. In Japan, an aggressive thyroid-cancer screening program boosted rates of diagnosis and treatment, but “the rate at which people died from thyroid cancer remained unchanged,” Mukherjee writes.

These findings show the limits of the “early-detection paradigm,” he explains. “Suppose we could install tiny sensors in people which would regularly scan their blood to find circulating tumor cells, conducting an ongoing ‘liquid biopsy.’ We’d be catching cancers earlier than ever before. But… we might also end up overtreating more cancers than ever before.”

Azra Raza. Credit: Kevin Mazur Getty Images

Mukherjee raised these concerns with Raza last month in a public conversation in New York, which I attended. When Mukherjee worried that her plan might lead to more overtreatment and higher costs, Raza expressed confidence that competition among biotech firms will improve the accuracy of tests and drive down costs. “Capitalism,” she said, will make her plan work.

Actually, free-markets forces have given us second-rate health care with sky-high costs, and excessive testing is a big part of the problem. As a recent critique of cancer screening in the European Journal of Clinical Investigation states, “Screening is big business: more screening means more patients, more clinical revenue to diagnostic and clinical departments, and more survivors in need of care and follow‐up.” Raza’s plan would make screening a much, much bigger business without necessarily improving our health. Not to mention issues related to privacy.

I sympathize with Raza’s yearning for a new approach to cancer. Cancer has killed people dear to me, too. But cradle-to-coffin testing is not the answer. So what’s my solution? In a recent column, I advocate a “gentle,” less aggressive approach to cancer, entailing much less testing and treatment.

Gentle cancer medicine “can only take root if we consumers demand it, and stop insisting on getting dubious tests and treatments,” I wrote. “We may never cure cancer, which results from the collision of our complex biology with entropy. But if we can curtail our fear and greed, our cancer care will surely improve.” I stand by that statement. Physicians should heed their own creed: First, do no harm.

Further Reading:

Meta-Post: Posts on Mental Illness

Meta-Post: Posts on Brain Implants

Dear "Skeptics," Bash Homeopathy and Bigfoot Less, Mammograms and War More

See also my free online book Mind-Body Problems