This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

The 2018 National Science Olympiad Tournament just ended. Thousands of kids and teens from around the country came together to take exams, calibrate their precision machines, and embrace challenges that would intimidate many college students. And now that the medals have been given out and the photos taken, a large number of those competitors will graduate. Years ago – back when I was a competitor – most people who graduated would move on. A few stayed involved, becoming coaches or event supervisors. But like so many sports and other teams, most legacies ended with high school. Recently, past competitors have started to realize that they have more in common than just memories. They are an alumni network, and they are bringing together the enthusiasm they once had for competition in a new role as active Science Olympiad alumni.

Science Olympiad (at least from the seventh grade on) reflects an almost sports-like model of competition that the “Olympic” aspect of its name would suggest. Each competition features 23 events that are spread across the 15-member teams. Competitors cross-train to handle different events, which span the academic spectrum and rotate each year to better reflect the cutting edge of science in each field. Just like a track athlete might train to do triple jump, long jump, and the 100-meter dash, a Science Olympiad competitor might be training for the genetics, forensics, and experimental design events in a given year. The tournament season can include local invitational events as well as the regional, state, and national tournaments for qualifying teams. As the season progresses, teams might get to move on from competitions held at local school districts to distant college campuses.

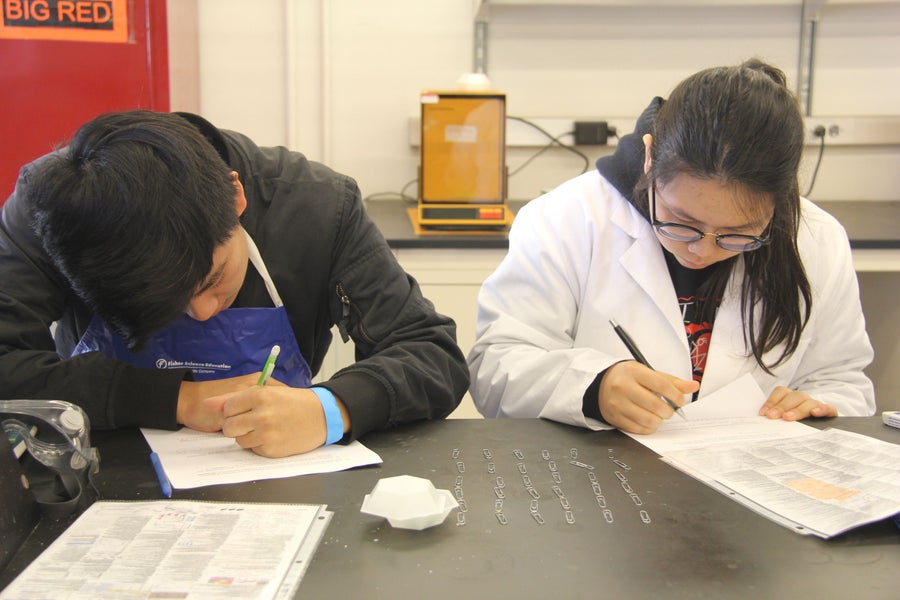

Credit: Golden Gate Science Olympiad

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Though the number of tournaments might not vary much between teams that make it to nationals and those that don’t progress beyond the regional event, the experiences associated with such events can vary a lot. Invitational tournaments are critical for preparing teams for the regional event. Invitational events may be the first time that teams see what it is like to handle three events in a row, see whether the binder they have compiled for resources is organized enough to use in real time, or calibrate their machines on the clock and with their competitors watching. Invitationals play a critical role in helping teams to make decisions about how to redistribute their members, redesign machines, or close academic gaps before the qualifying competitions. But invitationals are also a lot of work to run. The school districts that host events often have to depend on parents and teachers to volunteer their time to coordinate 23 events in a single day. Coaches are often called upon to write exams or run events to bring everything together. Because everyone knows how important invitationals are, people put in a lot of work to coordinate more than 150 around the country.

Once competitors make it to the regional, state, or national competitions, they see something a bit different. As a first-generation college student, my own regional, state, and national competitions marked the first, second, and third times I had ever set foot on a college campus. I got to walk among academic buildings with pretentious names, say I was heading over to the student union, and walk on a quad. At each level the exams were more sophisticated, the day felt more organized, and the competitors were more formidable. Teams that make it to Nationals face exams written by the national event supervisors and are supported by an army of volunteers. Some alumni remembered the effect that those later competitions had on them, and they wished that more students could have those experiences. Though the traditional tournament structure does funnel the most competitive teams to face off against each other, a standout student on a less-competitive team may not get the chance to see how they would fare against competitors from a top-tier team. Some alumni saw a chance to change that, and the college invitational was born.

Science Olympiad alumni on college campuses have started forming clubs and non-profits. They have lobbied their university leadership to provide venues to host competitions. The ‘About’ pages of many alumni groups have some version of a commitment to using their experience and resources to run a truly exemplary tournament. College invitationals bring together teams from a broad swath to complete with people they might not traditionally reach. The attendees might include a mix of top-tier teams that have traveled to square off against their out-of-state rivals and local teams that typically don’t make it past the regional stage. Standout students might get to see how they stack up against national winners. Exams are often written by past national medal winners or university faculty. Many alumni groups even strive to run the 23 events on the official national schedule for the year – a feat of labor.

Credit: Golden Gate Science Olympiad

The ever-growing list now includes tournaments run by alumni at schools like MIT, the University of Michigan, Dartmouth, UC Berkeley, Rice, the University of Georgia, Stanford, Cornell, Harvard, the University of Texas at Austin, Princeton, the University of Pennsylvania, Yale, and the University of Chicago. Jenny Kopach, Executive Director and Senior Vice President for Marketing and Communications for Science Olympiad, said it is almost like a competition to see who can launch the next and run the best invitational for their area – and each year more students are getting the chance to compete at a polished tournament on a college campus.

These tournaments also enable alumni to provide resources they wish their younger selves had had. Some invitationals provide teams that attend not only with rankings, but with full exams and answers to aid in training. Some provide the raw scores for all teams – letting students see how their mechanical events fared, not just how they ranked. Some campuses have rallied the faculty and are giving teams a chance to meet university professors. Some have obtained financial support to waive or reduce fees so that any team that can reach the campus can compete. Alumni even take the coaching experience into account, with a few events supplying enough volunteers – sometimes alumni flying in on their own dime – that the coaches can focus on their own teams.

So, as I congratulate this year’s winning teams – Troy High School from Fullerton, California (Back-to-Back Champs!) for Division C and Solon Middle School from Solon, OH (my own alma mater) for Division B – I am looking forward to seeing what those graduating seniors decide to do. I have been inspired by the way that so many alumni have created a new arena to provide elite tournament experiences, networking opportunities, and college exposure to a wider population of students. Far from simply re-living high school glory days, these alumni are trying to share the glory with more students than before. I am looking forward to being surprised by what they can accomplish again.

Note: I have participated in Science Olympiad in the past, both as a Competitor and National Event Supervisor.