This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

LEGOs may have been around since 1949, but their popularity is far from fading. The changing tastes of electronics-focused kids with household tablets and gaming consoles almost left the brand bankrupt ten years ago, but LEGO has since rebounded and even struggled to keep up with production demands in recent years. Rather than seeing the hands-on plastic bricks as a competitor for consumer electronics, robotics kits have provided a chance to bring building, programming, and problem solving together. Combine that with some friends and a competitive spirit, and you’ve got STEM programming that kids are itching to give up weekends or summer days to take part in. Between FIRST LEGO League, VEX Robotics competitions, and other programs, hundreds of thousands of kids and teens are taking part each year.

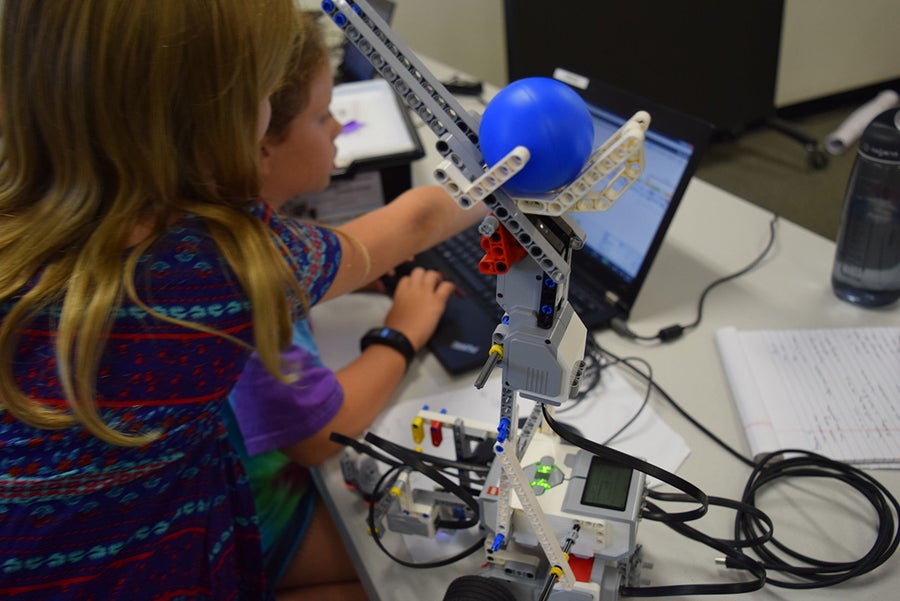

Credit: Amanda Baker

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute’s Center for Initiatives in Pre-College Education (CIPCE) has been running a variety of engineering and robotics camps for years. This year’s Jr. LEGO EV3 Robotics Engineering Academy gave 8-10-year-olds a chance to build a robot based on the LEGO EV3 software. Each pair of students started with a programmable motor and box of parts, but they had to work out the solutions to a series of challenges themselves. Most of the kids had experience building with LEGOs at home, but many had no programming experience before starting the week-long camp. By the time I visited on Wednesday, the students were building and adapting codes for the various sensors on their robots with ease. Ella (10) was surprised that they started with coding on the very first day. When I asked whether she felt like she had learned less than she would have if they had taken more time to introduce the basics, she had to sit and think. “No, really I don’t,” Ella said. “This way I knew what I was trying to do with it, so all the pieces made sense right as I learned them.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The challenges were quite involved, requiring a suite of sensors to follow lines, avoid prohibited areas of the board, steer around obstacles, and aim projectiles. Phillip and Josiah (both 9) had particular trouble with getting their robot to travel along a squiggly path marked on the ground. “Oh man, we spent hours getting that to work,” Phillip said. But it was clear that the hours they spent were a point of pride, not embarrassment. When asked which parts they would pick out for future students to work with, many of the students named the parts that they personally had struggled with the most. Dylan (8) put it bluntly: “Because that part was really hard for us, and challenges are supposed to be hard.”

Credit: Amanda Baker

In addition to the progressive set of challenges, students felt that they had learned from the partnerships themselves. Most of the students had only met their partners at the start of the week, but they already had a clear sense of their collective strengths and weaknesses. John (8) and Cody (9) came in with notably different skill sets. “Cody had way more programming experience,” John explained. “Like, he can just totally make things work.” Cody jumped in to return the praise, “And John can build things just like that! He knew how to make a catapult right away,” Cody said. Practically finishing each other’s sentences, the new partners were clearly enjoying working together. When Kevin Allen, one of the facilitators, asked what they would do if they had to switch roles the next day, the boys both looked dismayed. Mr. Allen then suggested that perhaps they could teach each other their skills, and John and Cody immediately started sharing their work.

While the students took a clear lead in their own projects, the facilitators took many opportunities to poke holes and push the teams to think more deeply about their decisions. One pair was struggling to get a catapult to hit a target and were about to move some pieces on their robot. A facilitator asked them to think about the effects of changing design versus code this late in the game. Any changes in the physical robot, they realized, might affect some of the code that was already working. With two days remaining at the camp, I was impressed at the depth of understanding on display on day three. Braden (10) slipped naturally into analogies when explaining the team robot: “These wires here bring information to the motor, like nerves bringing information to the brain.” Meanwhile, Alex (8) was troubleshooting some conflicting loops in their program.

Credit: Amanda Baker

All of the pairs had succeeded so quickly with the initial challenges that the facilitators had to add new levels on the fly. Even experienced groups like CIPCE leave room to accommodate for the shifting baselines in technical ability and creative confidence in students each year. We can only hope that other STEM and STEAM programs are stepping up to take advantage of this growth and push students even further nationwide.