This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Parents and teachers who are searching for ways to engage kids with local environmental issues might look to their community parks or science museums for opportunities. But what about art? Environmental issues can often be overwhelming or disheartening for members of the public, and art offers an innovative way to promote interest that can lead to deeper engagement down the line. This approach presents a particular opportunity for younger audiences, combining activities they love – like coloring, building, and crafts – with the basics of environmental issues.

Early environmental movements in the US tended to focus on very local and tangible issues – stopping the pollution of water or getting smog out of the air. Climate change has shifted the focus to more global threats, which has the dual effect of making the problem seem insurmountable and making the apparent threat more abstract. Research societies and environmental groups are again turning their focus more locally. They are hoping to promote a sense of environmental stewardship: the sense of responsibility to use conservation and sustainability practices to protect the natural environment. This sense of responsibility relies on the development of personal buy-in, something that often depends on an emotional connection for long-term staying power. Art has the potential to cultivate that emotional connection.

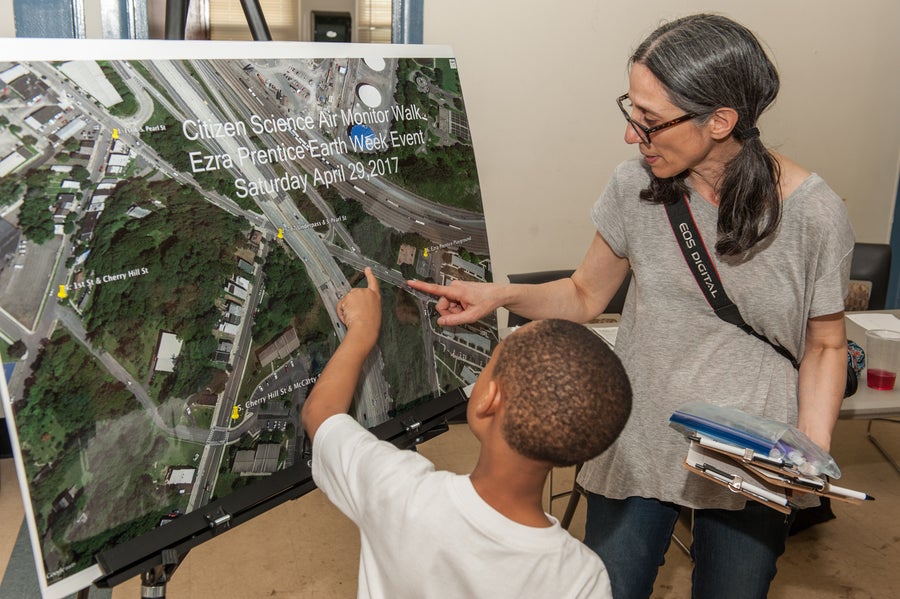

Mapping Rover data with a young citizen scientist. Credit: Ray Felix, Courtesy of Maria Michails, 2017

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute PhD student Maria Michails has been using art to facilitate public engagement with environmental issues for years. Her earlier works were designed for galleries and sought to create a bridge between audiences and concepts of environmental risk. The exhibits highlighted agricultural water usage or petrochemicals and depended on the physical effort of audience members on bicycle gears or hand carts for the display. The Petri Series focused on benzene projected microscopic colored stains of cancer cells as aesthetic elements, as one might use photographs or paintings. But the beautiful images depicted cancer. Such a stark emotional connection opened a door for further engagement with the petrochemical threat itself.

Gallery exhibits had provided a unique forum to expose audiences to new ideas, but Michails wanted to engage the audience as more than observers. This led her to a community meeting held by the Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) and a discussion that revealed some important shared goals. The DEC has a long history of community education and science outreach, as well as important expertise about the most critical environmental risks facing a given region. Michails has her own experience connecting with audiences through socially engaged art. The subsequent project presented a chance for Michails to engage the participants through art and the DEC to recruit potential participants as citizen scientists for their air quality study.

Air quality monitoring rovers. Credit: Ray Felix,Courtesy of Maria Michails, 2017

While science outreach has always been a balancing act to find the right type and level of content for a target audience, socially engaged art contributes an additional layer to identifying the right medium. With a target audience of late elementary students to early middle schoolers, the final format for this project ended up being hands on, had a clear creative aspect, and gave the students a chance to interact with some interesting technology: rovers. Young participants were given the chance to decorate and customize remote controlled vehicles equipped with air-quality sensors. The idea was that first taking the time to design and decorate the rovers would increase the sense of ownership that the kids felt they had in the activity. The custom rovers then drove through the neighborhood taking measurements and giving the kids a chance to collect air quality data. This provided the unique opportunity for real-time feedback about the air quality around them. Looking at data may not be compelling for middle schoolers, but watching an instrument spike as a car drives by can elicit a genuine “whoa!” Ultimately the students had a chance to display their rovers and data.

Citizen Science Rover Walk with community members of Ezra Prentice Homes, South End Albany, NY. Credit: Ray Felix, Courtesy of Maria Michails, 2017

As with any STEM outreach, the hope is that the experience will provide something that lasts longer than the duration of the activity itself – new content knowledge, new skills, new perspective, or even new questions. For Michails, the last piece was the most important. While it is rewarding to see young people excited while they are decorating or taking measurements, a sense of environmental stewardship will keep them asking questions long after they head home. Perhaps art can help forge some of the connections that will keep people coming back and thinking about the environment around them as something they want to protect as their own. Future collaborations will certainly help us find out.