This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

I am fascinated by people who mix modalities, who are always on the lookout for hidden meanings, and who have a real commitment to the truth and mutual understanding. The artist Jayne Riew ticks those boxes. Riew, who has a graduate degree in English literature, has worked in a variety of visual media, from painting to printmaking to photography. In recent years she has produced three main projects that combine text and image to explore questions of emotion, motivation and meaning that may interest readers of my column. Below I'll briefly describe each of these projects and then present a discussion I had with Riew about her process and motivation.

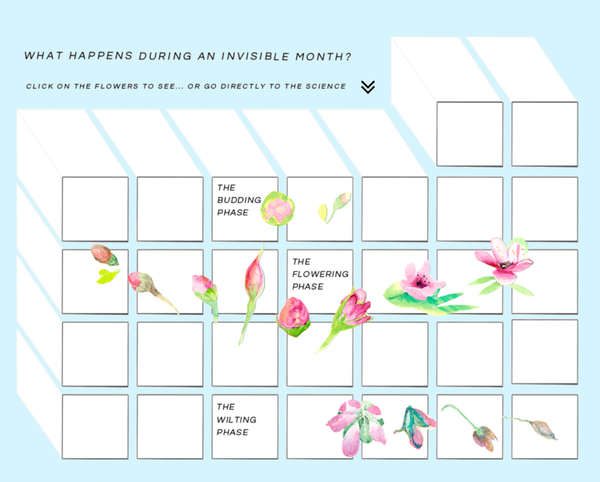

1) The Invisible Month

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

An illustrated guide through a young woman’s reproductive month to show how hormones affect work, sexuality, and mood.

Jayne illustrates the phases of the “invisible month” using iconic images of women in art. She offers signposts along the way suggesting how to optimize success and self-care.

Credit: Jayne Riew

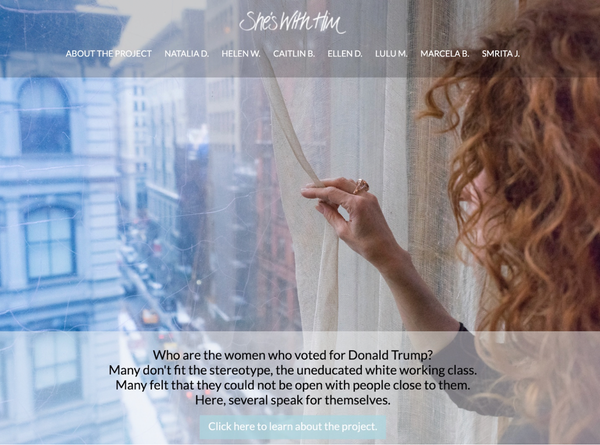

2) She’s With Him (ShesWithHim.com)

A photo essay

After the 2016 presidential election, it was estimated that 42% of women had voted for Donald Trump. Jayne guessed that female Trump supporters knew they had to keep their voting intentions hidden, not just from pollsters, but from people close to them. This portrait essay features seven women who did not conform to stereotypes about Trump voters, and who shared their positions and motivations.

Credit: Jayne Riew

3) Twisting Ladders (TwistingLadders.com)

A photo essay

This is a portrait essay looking at how people respond when presented with unexpected information about their origins after taking a genetic test. Twenty volunteer subjects share how they grappled with the news of a child, parent, or sibling.

Credit: Jayne Riew

Your work is deeply psychological. Do you consider yourself a psychological artist?

Decades ago during grad school in literature, I would look for human motivation in all my interpretations. During those years of close reading I realized that the most fraught moments in every good story are rooted in the unseen or unspoken. What we hide from ourselves, what we hide from public view. When I moved to visual art, I still wanted to explore human behavior and choices, and how we see ourselves and the world. Art can serve many functions, including self-awareness and growth.

Between my lives in literature and art, I got to know the field of positive psychology and the power of intuition. My project, The Invisible Month, is an illustrated tour showing how young women are nudged from within. It's further invisible because sometimes the reasons for our actions are hidden even from us. The suggestion is that if women know what’s happening inside, then they can better engage with the challenges of life, at the very least by controlling the timing of some of those challenges.

Your first two projects waded into some potentially controversial areas. Evolutionary psychology applied to women’s behavior, and empathy applied to Trump voters. Did you face any blowback?

The Invisible Month drew criticism from some people who objected to anyone saying that women are variable in their inclinations and aptitudes. And to think-- it was presented with handpainted flowers, so imagine the freakout if I had expressed the idea directly in an op-ed or journal article! I purposely styled it to be approachable, friendly and inviting. First the eye opens, then the heart and the mind follow. That was my hope, anyway. The risk was greater when presenting portraits of Trump voters. Sure enough, I got some nasty emails. The thing is, although I voted for Hillary, it disheartened me to see women demonizing other women who voted differently. In She’s With Him, I wanted to suggest that social harmony starts with women. We are the natural nurturers, empathizers, and maintainers of relationships. That’s one of the reasons portrait photography compels. Portraiture has the power to help people humanize strangers.

And yet your work is informed by science, even bolstered by it. Is that accurate to say?

Absolutely. Whether we are makers of art or consumers of it, art helps us feel wonder. Things that you can't necessarily put into words. While I appreciate the world of science and reason, I don't live there. Often I have intuitions or premonitions that I don’t understand, but turning to science often makes it sensical.

With the Invisible Month, my process could not have been more accidental: from month to month, I kept noticing patterns in my own behavior. One day I looked it up on Google Scholar. Then I fell down a rabbit hole because there were all these studies explaining why I wanted to binge on donuts three days before my period, or was a total workhorse for the two weeks after my period, or felt overcome by lust for the same few days every mid-month. Then it occurred to me, shouldn’t this be common knowledge-- how female reproductive hormones fly under the radar of consciousness?

Increasingly we live in a world where so many phenomena can be explained by the experts. Yet sometimes it is only visual art that can help us "see" what can't be expressed by words alone. A lot of people were unsettled by The Invisible Month because they felt I was saying that if a woman says no to a request of any kind, just ask her again in two weeks and she'll say yes. No, it's much more complicated and subtle than that. But to get to the subtlety you have to be willing to be more whimsical, imaginative. That's why the project is mostly hand-drawn paintings of flowers over the course of life. But if I'd had the space and the resources, I would have made the project an immersive installation where people feel infinitesimal and compelled by the irresistible forces of nature as they’re hurried through the life stage of a flower.

In your DNA photo essay, Twisting Ladders, how did people deal with finding out that they weren’t who they thought they were, at least, genetically speaking?

To me the most thrilling, odd, and beautiful thing about this technology is that it can make family out of total strangers. Of course, accepting that family is a choice, one that might upset members of one’s current family. Whom we choose to love, whom we'll let into our lives, whom we resist, and whom we welcome. That is life itself.

But the really touching thing is how my volunteers all exhibited a host of strategies for accommodating their news: acceptance of the past, curiosity, hope for the future, prayer, life satisfaction, gratitude, self-compassion, compassion, and growth mindset.

My volunteers, when it was revealed to them that they had siblings, or a parent or a child with whom it was possible to unite, weren’t fixated on how this rocked their sense of self. And even when it was relevant, they didn’t pause for long on the racial or historic significances. Instead, the question that was paramount was, how will this new relationship guide my life moving forward?

What drives you to create? You don’t sell your artwork, you don’t seek out commissions, you just put it out there. What’s at the heart of your work?

The one thing I've designed for mass production is a meditation box called Be Still. It has the dimensions of a small laptop but when you open it, there's a thin layer of sand and a stylus. You write something, then close the lid and shake it. And then the inscription is gone. The idea is: behold the moment, let it pass, move on. There's power in the witnessing. My favorite moments in art and literature are the fanciful, because fancy gets at what's true. It gives us access to aha moments that aren't available to us otherwise. One of my favorite ideas is from Milton, who explains why Satan is restless. Satan is driven to hell because he's never able to find a still point in a turning world. That is at the heart of all my work. My photo essays and The Invisible Month share this inquiry: hey you, are you really paying attention? In a way we are all like cameras, hunting for focus. There’s so much out there in the picture plane of our worlds, all competing for our attention, we get distracted.

What can portrait photography teach people about life?

Portrait photography is empathy. It's about how well you sense another person. Sometimes I feel like we've forgotten how to take time to get to know others in a meaningful way. That takes care and consideration. Everyone is busy with this and that. But there is something so arresting about seeing another person well. To me a good portrait is a reminder to take time. People come first.

What is the best advice you've ever gotten as an artist?

The best advice I ever got as an artist was given to me not by a fellow artist but by a scientist. A woman. A mother. The UCSB psychologist Leda Cosmides told me over dinner when I had a two year old son, "Enmesh yourself in his subjectivity." At first I thought, here we go, another scientist using the lexicon of the laboratory. But then I thought about it. And she is so right. And it was more poetic, more succinct, and more idiot-proof than anything anyone has ever said to me since about parenting or portrait-making.

I had this friend long ago whose five year old granddaughter said while touching her face, "Grandmother, I love your designs." She was talking about the lines that crisscross the face of an elderly person. I long to have that kind of beginner's mind, to start every project with no preconceptions or evaluations. But it's hard. I'm almost 50 and I have expectations. For example, for this last photo essay, I did all this reading beforehand on modern identity. When I started the actual interviews--once I had enmeshed myself in the subjectivity of others-- I realized people weren’t interested in identity. They were deep in the throes of connecting with others, and their sense of self remained steadfastly intact.