This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

A treehopper ponders the big wide world from the inside of a house. Photo by Kalliopi Monoyios (Sci Am blogger for Symbiartic!) Used with permission.

Chances are you have never heard of a gall midge or a book louse. But odds are also good, at least if you live on the mid-Atlantic seaboard, that they know about you. That’s because you’re roommates. Nearly 100% of 50 houses surveyed in and around Raleigh, North Carolina, contained these insects.

That was the surprising conclusion of a new study by entomologists at North Carolina State University -- including Sci Am guest blogger Rob Dunn -- that aimed to document the insects, spiders, and other arthropods of a random sample of homes.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The scientists sought to probe a largely uninvestigated yet very personal frontier: the tiny animals that dwell with us. Although scientists have intensively studied pests, almost nothing has been done to survey everyone else -- and everyone else turns out to be the silent majority. Unnoticed and overlooked by humans, we don’t know if these other animals are helping, hurting, or having no impact whatsoever on us, nor do we even know who they are and how many of them there are.

To remedy that problem, the scientists randomly selected 50 free-standing homes from a list of volunteers who had filled out a survey about their residence and its residents. All 50 dwellings were within a 30-mile radius of the center of Raleigh, and the homes ranged in age from seven to 94 years old. Entomologists combed through all rooms except attics and crawl spaces; for reasons of safety, only a two meter radius from the entrance of such spaces was examined. Oddly, the safety reasons cited were heat and confinement, not the presence of an army of hella scary creepy-crawlies.

Stand back, ma’am. I’m an entomologist.

The team collected every visible insect inside each room with forceps, vacuums, or nets, looking under and behind furniture, around baseboards, ceilings, and on shelves and any openly accessible surface. They did not, however, open drawers, cabinets, or look inside walls or under heavy furniture. They did pluck the victims from spider webs. All confiscated insects were promptly soused in 95% ethanol.

After scouring the literature to identify all their specimens to family, they compiled their data in tables. Most people like to think they are living in a relatively sterile, and at least mostly animal-free (small pets and children excepted) environment. However, the data contained in these tables belie those beliefs.

First, the prevalence of insects in homes was surprising, the authors said. Nearly every room contained insect occupants. And the diversity was enormous. All together, the scientists found at least 579 different species. Each home contained an average of 93.14 physically distinguishable species from 61.84 arthropod families, ranging from 32-211 species and 24-128 families. Given the somewhat superficial approach to insect sampling (drawers, cabinets, wall-interiors, and attics being well-known insect haunts), the true number of species in each house was likely higher. Bigger homes generally had more species, an unsurprising correlation.

Given that this survey was limited to homes in a 30-mile radius of Raleigh, North Carolina, the true diversity of insects found in homes in the United States, not to mention the globe, must be staggering.

Because so much past research on insects in homes has centered on structure- or health-threatening pests, the authors expected them to be among the most commonly encountered arthropods. Instead, they found a relative lack. Pests were found; cockroaches were sighted in 82% of homes, though most were non-pest species (the pestiferous German and American cockroaches were found in only 6% of homes each). Scavenging carpet beetles were found in 100% of homes; in some instances, dog kibble became carpet beetle kibble, along with dead insects and nail clippings, but the larvae of these pests usually eat natural fibers and feathers found in clothing, upholstery, or carpet, dust, and lint.

Termites were found in 28% of homes, clothes moths in 60%, fleas in 10%, and mosquitoes in 82%. No doubt to homeowners’ great relief, bed bugs were not found anywhere. Dust mites were found in 76% of homes, which may not seem surprising until you think about how ubiquitous they are considered to be and what other insects were found in 100% or near 100% of homes: springtails in 88%, book lice in 98%, gall midges in 100%, dark-winged fungus gnats in 96% (by contrast, fruit flies were only in 66%), and ants and cobweb spiders in 100% (okay, last two maybe not a surprise).

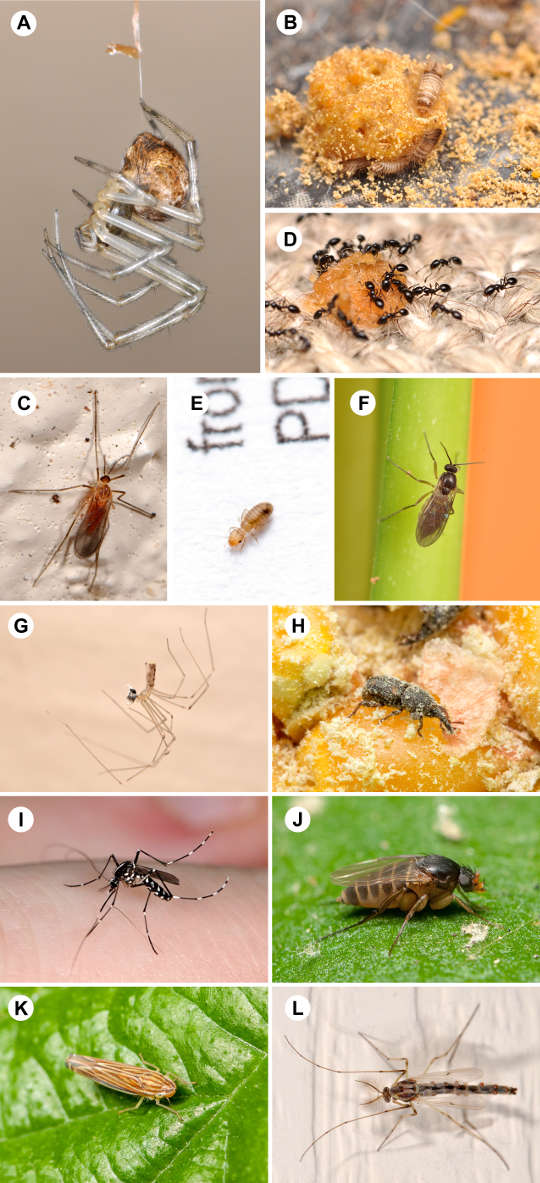

The most frequently collected arthropod families from homes in this study. (A) cobweb spiders (100% of homes) (B) carpet beetles (100%) (C) gall midges (100%) (D) ants (100%) (E) book lice (98%) (F) dark0-winged fungus gnats (96%) (G) cellar spiders (84%) (H) weevils (82%) (I) scuttle flies (82%) (J) scuttle flies (82%) (K) leafhoppers (82%) (L) non-biting midges (80%). Fig. 4 from Bertone et al. 2016. Photos by Matthew A. Bertone.

By now you may be wondering, all right, I’ve made it this far. Are you ever going to tell me what a gall midge or a book louse is?

Gall midges are tiny, delicate flies – usually only two or three millimeters long, but often smaller than a millimeter. Their home is on or near plants. They have long antennae and, interestingly, hairy wings. Perhaps all the hairs act as drag strips that help the elfin insects float on the breeze.

By Unknown - http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/6825#/summary, Public Domain

As larvae, gall midges suck plant juices and cause tumors called galls to form on their hosts. Some gall midges prey on or parasitize other crop pests like thrips, whiteflies, aphids, spider mites, or scale insects. Despite the fact they were found inside each and every home in this study, a recent compilation of city-dwelling insects and arachnids failed to list them in a roster 2,000 species long.

No respect.

Legs 'till Tuesday: a gall midge. By Alvesgaspar - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

What were they doing in all these houses? We’ll get back to that in a minute.

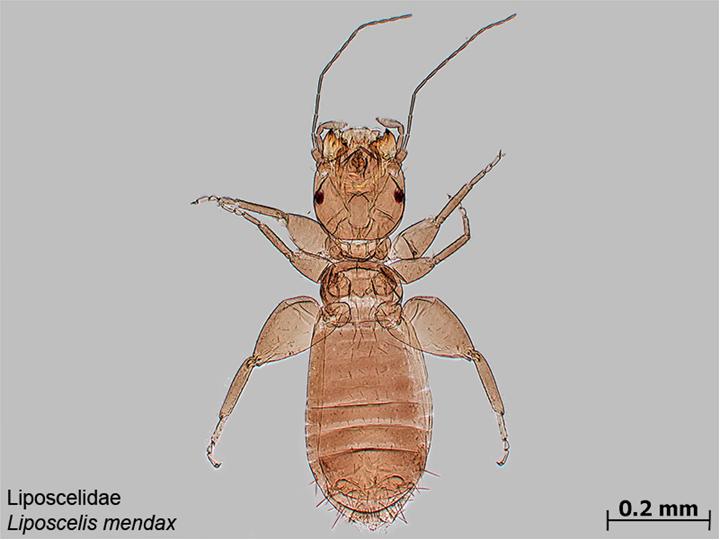

Book lice are close relatives of the body and hair lice that have plagued humans for millennia. They are tiny – less than a sixteenth of an inch long – and wingless. Also kind of cute. It's those little beady eyes.

A book louse. Fig. 4E from Bertone et al. 2016. Photo by Matthew A. Bertone.

By MAF Plant Health & Environment Laboratory - http://www.padil.gov.au/maf-border/pest/main/141694, CC BY 3.0 au

However, instead of sucking blood or munching skin, book lice eat the mold that grows on household detritus, wallpaper paste, potted plant soil, or stored grains. As you can imagine, this is an insect that thrives in the same humid climates that yield soggy cereal and moldy books -- hence the name.

In contrast to these common but obscure insects, dust mites, allergens of great fame, were present in about three-quarters of dwellings. As expected, more mites tended to be found in carpets (carpets trap food and moisture, and shield and insulate mites), but the most mites of all were found in a wood-floored home, proving hardwood is no guarantee. Humidity and vacuuming habits may play a role, the authors suggested, or gaps in floorboards could act as dust mite nature preserves. For those of us without dust mite allergies, however, dust mites are likely the best, lowest maintenance pets we’ll ever have. They’re so quiet you’ll never even know they’re there, and you already clean up after them every time you vacuum or sweep. So what if you need a microscope to play with your pets?

Many more surprising denizens made cameos in the survey, including earwigs, jumping bristletails, death watch beetles, assassin bugs, silken fungus beetles, fireflies, blow flies, phantom midges, freeloader flies (near the couch?), fungus gnats, goblin spiders, stone centipedes, and woodlice. Parasitoid wasps that attack the insects found in homes were also found, including one that attacks blattid cockroach egg cases. That one was commonly found in homes along with its host, and must be a welcome guest were its human companions to know of it.

Many of the unexpected species seemed to have flown, wandered, or drifted in from outdoors and either become trapped or expired before they could escape. In effect, houses may act like passive samplers of the “air plankton”(love!) – a menagerie of tiny semi-drifting airborne animals like gall midges. In this way many of the animals found in homes may be more a reflection of the outdoors than the indoors.

For instance, leafhoppers, like many plant pests, are more or less botanical mosquitoes; they make a living piercing and sucking the juices from plants, and as such must have little interest in the interiors of all but the leafiest homes. Yet they were found in 82% of homes in this survey. On the other hand, there was a surprising lack of moths and butterflies given their abundance out of doors. They made up only 2% of the average diversity in a room.

[Some species were surprising because they are rare anywhere, ant-loving crickets being but one example found in homes infested with ants.

By Gunther Tschuch - Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5

Another rare surprise was primitive beetles from the order Archostemata, which resemble Earth's first beetles.

One house contained a "rarely-seen" larval beaded lacewing, a parasite of termite nests. They emit a chemical that paralyzes termites, allowing them to dine upon them.

Adult beaded lacewing -- a thing of weird beauty. By Lucinda Gibson, Museum Victoria - http://www.padil.gov.au/barrow-island/pest/main/137029/10013, CC BY 3.0 au

A few other lurid curiosities: flesh flies emerged from a rodent killed by a house cat in one home, while centipedes that prey on other insects, and spitting spiders – which can shoot sticky silk-laced venom a centimeter away to grab prey – were found in others.

Our civilized habits have also reduced some insects’ abundance while boosting others’. The advent of indoor plumbing has reduced (but not eliminated!) dung beetles in our homes. But it has also provided new horizons for drain-dwelling moth flies, who are likely more common now. House flies, German cockroaches, and fruit flies have piggybacked on our spread to launch themselves to worldwide success. The German cockroach doesn’t even have wild populations anymore.

Some of the most common insects in our homes gained that status because they’ve been rooming with us since we lived in caves – literally. Of the pest species found in this study, many have been recovered from archaeological sites: grain weevils; carpet, grain, cigarette and drugstore beetles; and house flies. Bed bugs evolved from a species found in bats, and were most likely picked up during our cave-dwelling days. Disease-transmitting kissing bugs may have been acquired the same way at least 26,000 years ago.One of the first known works of cave art depicts a camel cricket -- a group of insects found in 58% of the homes in this survey.

These insects have been with us a long time, and – understandably -- appear to have no intention of dropping the acquaintance. Yet it appears, at least based on this limited sample, that the majority of insects found in our homes cause us no harm, headaches or unsightly welts, and probably didn’t even want to end up there in the first place.

Reference

Bertone, Matthew A., Misha Leong, Keith M. Bayless, Tara LF Malow, Robert R. Dunn, and Michelle D. Trautwein. "Arthropods of the great indoors: characterizing diversity inside urban and suburban homes."PeerJ 4 (2016): e1582.