This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Lots of people get worked up about orchids, the apogee, or something near it, of floral extravagance. They are plants whose flowers are so potent they can produce lust bordering on obsession. Their seeds, on the other hand, produce disdain. “Dust seeds,” botanists and fanciers alike scoff. Rarely has anyone bothered to take a closer look.

Over the last four decades, a team of German scientists finally did. Four years ago they published the first-ever monograph of orchid seeds, which documents their understated beauty and sometimes surprising complexity with thousands of scanning electron micrographs. Their findings demonstrate that orchid seeds are not as wholly uninteresting as their size suggests.

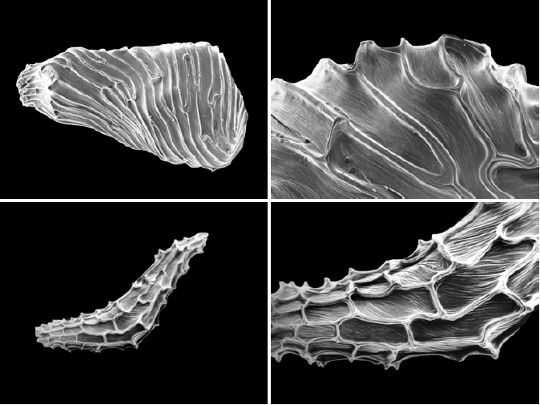

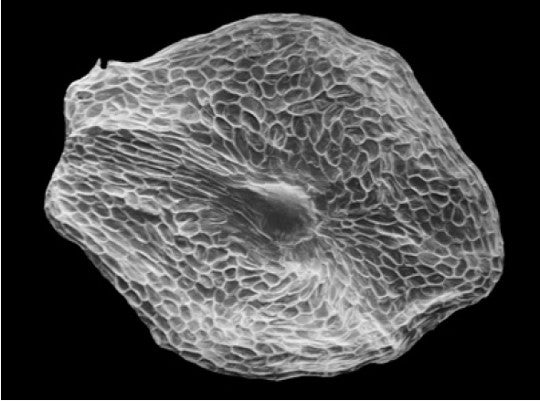

Even the simplest and smallest have a beautiful textured balloon-like coat that hides the miniscule embryo inside an air-filled cavity:

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

.jpg?w=540)

Special scanning electron microscope technique reveals the air-filled interior and simple embryo. Credit: Barthlott et al. 2014

The cells that construct the seed coat are so truly tiny that you can see (and count!) them. The ridges between them can give the seed a sculpted look.

Credit: Barthlott et al. 2014

An orchid named Vanilla is the source of vanilla extract and vanilla "beans". The seeds of Vanilla and its kin have a flattened blade to help them sail away on the wind, like the wing of a maple seed.

Seed of Epistephium parviflorum, a Vanilla relative. Credit: Barthlott et al. 2014

Something like this thing is what you're eating any time you eat vanilla bean ice cream. These are the tiny black specks.

Another species, Microcoelia obovata, produces seeds covered in tiny hooks. Their object is to secure a home on the bark of new twig, the preferred home of the epiphytic plants.

Seed coat of Microcoelia obovata. Credit: Barthlott et al. 2014

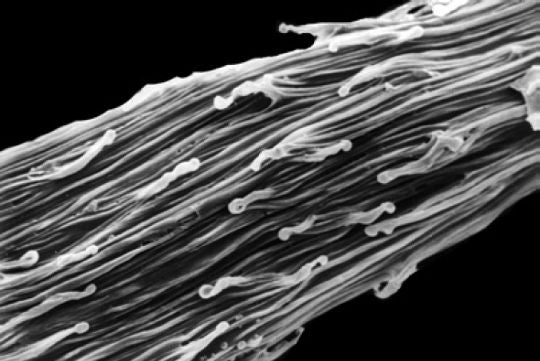

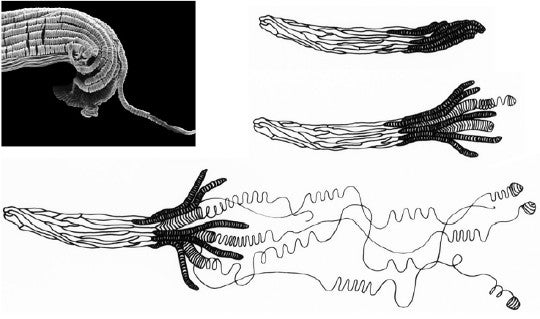

But the orchid Chiloschista lunifera has taken this tactic right up to 11.

Chiloschista lunifera. Credit: Barthlott et al. 2014

The seed coat cells on one end of the seed possess helical wall thickenings. When wetted, they unspool in a tangle that performs the same job as the hooks on Microcoelia .

Chiloschista is interesting for another reason. Although its seeds are elaborate, the plant itself has opted to forgo that most basic of plant organs: the leaf. It's a bundle of green stem-like aerial roots that miraculously sprouts yellow flowers.

This orchid brought to you by Snidely Whiplash. Credit: Naoki Takebayashi Flickr(CC-BY-SA 2.0)

So why are orchid seeds so miniscule? Answering that question requires a short tour of the plants' unconventional reproductive system.

Orchids are renowned for their extravagantly sculpted, pigmented, and perfumed flowers (although I love orchids, frippery is the word that comes to mind) and keen interest in alternative plant lifestyles (like giving up leaves and living in trees).

One of those alternatives is a reproductive system referred to “lottery pollination”. The grand prize in the lottery is a packet called a pollinium. The pollinium is the plant equivalent of the animal spermatophore – a big package of sperm, or in orchids’ case, pollen (and since pollen makes sperm, it’s a fine distinction in my mind.)

Pollinium indicated by arrow. Contents indicated by, er, conveniently convergent shape. Credit: Esculapio Wikimedia(CC BY-SA 3.0)

When a pollinator visits an orchid flower, the pollinium has evolved to detach and stick to them, with often comical results.

If all goes according to plan, that pollinator will visit another orchid of the same species. The pollinium will stick to this flower’s strategically-placed stigma. And then all the pollen stuffed inside the pollinium will fertilize all the thousands of awaiting eggs inside a new orchid fruit. You win big, or you win nothing.

As a result of this system, some orchids are going to waiting a long time for fertilization to happen, and consequently, their unfertilized flowers are some of the longest-lasting in the business. They can stay fresh-looking for a month or more, one reason they are so prized as houseplants.

In some ways, an orchid is like a salmon: it makes scores of offspring and doesn’t invest much in any of them. The result is tiny seeds. Most are less than a millimeter across and some are as tiny as the largest fungal spores – just 100 micrometers across.

What’s inside is spartan too. A seed is a plant embryo supplied with a food care package called endosperm to help the embryo get started. In plants like wheat and corn, the endosperm persists in the mature seed and is the source of white flour. (Whole wheat flour also includes the high-fiber seed coat, or bran, and the nutritious plant embryo, or germ).

Orchid seeds almost always lack endosperm. No sack lunch for you, kiddo. Instead, the seeds must find a special fungus with which to partner and germinate, and it is this fungus that supplies a baby orchid with startup food.

In addition, the mother plant boots the seeds out of the nest when the embryos inside are still only a few cells big. In other seeds, the embryos are usually so well developed you can see a tiny version of an adult plant in there, as anyone who’s ever looked inside a peanut has noticed. Orchid embryos are microscopic blobs.

As a result, an orchid seed is stripped down like a broke poker player. There’s an embryo. There’s a seed coat. And that’s about it. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t interesting, beautiful -- or helpless. They have what they need to get the job done.

Reference