This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

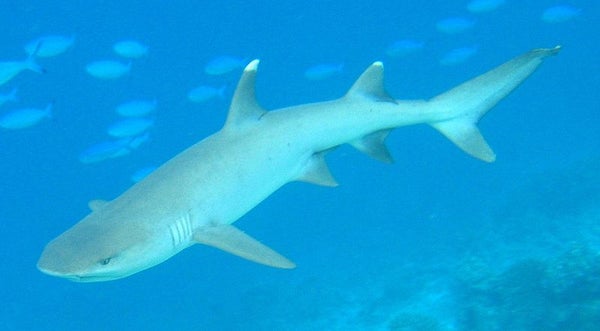

Whitetip reef shark in Fihalhohi, Maldives. Credit: Jan Derk Wikimedia Public Domain

Following last week’s news that the world’s oldest living vertebrate is the Methuselah-esque Greenland shark, another interesting shark-related tidbit recently popped up in the scientific literature: the ominous background music that inevitably accompanies sharks on screen damages their image with viewers, according to a new study in PLOS ONE.

Although many humans have wished for their own awesome soundtrack to follow them around wherever they go, sharks may feel differently. Though having a bada** reputation no doubt instills the proper respect among fish, the effect on humans can be considerably less desirable: reduced support for shark conservation and more attacks on sharks by humans (shark killings famously spiked after Jaws hit theaters). Waaaaaaaaay more than they ever attack us.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

That’s bad, because sharks, like wolves and bears and any number of other predators, play an important role in nature. Yet their numbers have dwindled due to overfishing, the wasteful and destructive practice of finning them for shark-fin soup, and damage to their habitat. As a result, a quarter of shark species are considered “Threatened” by International Union for the Conservation of Nature(IUCN) criteria.

Yet as much as sharks need help, money for helping them has not been as forthcoming as money for marine mammals and turtles. It is hard to convince the public that sharks need and deserve their support.

People also consistently overestimate the risk of shark attacks. In Australia, a study of 766 adults found that as a group they estimated there were seven to nine fatal and 20 to 30 non-fatal shark bites each year. In reality, the numbers are an average of 1.1 and 9.3 for all of Australia from 1990 to 2010. This is part of a general tendency for humans to overestimate the probability of rare events that are easy and horrifying to imagine – plane crashes being another premier example. Vivid portrayals of sharks in movies and documentaries are part of what makes them so easy to imagine.

The role of the music in those portrayals may also have been underestimated, the authors said. Although nearly everyone associates the foreboding Jaws theme with sharks, the music in less overtly threatening nature documentaries may also play a role in shaping people’s attitudes, and in turn, their likelihood of supporting shark conservation.

It would not be the first time that background music has been found to alter people’s perceptions without them even realizing it. For instance, even wine can be made to taste like the music accompanying the tasting. One study found that when a “zingy and fresh” soundtrack played, tasters were more likely to rate the wine as having that property than “mellow and soft”. Yet the same wine was significantly more “mellow and soft” when music appropriate to that idea was playing. Très intérressant.

In this study, scientists exposed human subjects to 60-second clips from shark documentaries set to “ominous” music, “uplifting” music, or no music. The clip used was from the “Ocean World” episode of the BBC documentary “Blue Planet”, which I’ve personally watched and greatly enjoyed. It’s high-quality nature documentary-making at its finest.

Here is what I believe to be the clip (starting at about 2:20), along with music similar to that used in the study, which was chosen off the "Blue Planet" soundtrack because it so closely resembled what you hear here. I don't think the subjects of the study got to hear David Attenborough, though.

Wow. Now that I listen closely, you can hear that the music even uses percussion to mimic what sounds to me like a heartbeat – a pounding heart being a well-known harbinger of fear.

If you want to listen to the actual music used in the study, it is 1:45 to 2:45 of this track. If you listen to the whole track, it quite nicely encapsulates the authors’ point:

The “uplifiting” musical clip was 1:41 to 2:41 from Track 1 of the Blue Planet soundtrack, which you can listen to here:

Unsurprisingly, the group that watched the clip accompanied by the “ominous” music rated sharks worse than the other two groups after watching the clips. As another control, the scientists asked other volunteers to listen to the music alone without images of sharks accompanying them. Their ratings of sharks did not differ from each other.

However, there was no difference in the willingness to donate to shark conservation measures as a result of any treatment, except in one of their three experiments. In this version, there was a slight benefit to conservation from watching the clip with the uplifiting music, but no detrimental effect of watching the ominous music compared to silence. So perhaps even if documentaries make us fear sharks more, we can think more objectively about them when it comes to choosing to help protect them.

Nonetheless, the authors urged readers to contemplate that nature documentaries are often viewed as “objective” sources of information, yet they may be unintentionally biasing viewers against sharks in ways that could have serious repercussions. It certainly seems like a point worthy of consideration.

Last March I was snorkelling off the beach next to the power plant on the west end of Oahu, near the seafloor hot water discharge. It attracts fish. We’d seen a few big fish, but nothing huge, and we started to swim toward a reef nearer to shore. Suddenly my brain alerted me to a big fish moving my way. After a further few seconds my brain further alerted me that this fish was a shark, which generated a jolt of fear. Though 20 or 30 feet below the surface, it was swimming right toward me.

But I could also see a white tip on the shark’s tail. Through prior research for my open-ocean night dive, I knew it was most likely a whitetip reef shark. Generally, these sharks are docile and harmless. I was able to watch the shark swim toward, me, then to my left, then behind me. Fear gave way to awe, excitement, and privilege. The shark was maybe five feet long. And it was wild. And I was swimming with it.

Shark attacks on humans are exceedingly rare. Yet we kill them by the millions - possibly hundreds of millions -- each year. As I and probably countless others can testify, getting the opportunity to swim with one is much more likely to be magical than dangerous.

So if sharks’ current soundtrack is not working for them, obviously they need a new one. I polled Twitter for suggestions. May fave so far? Theme from Seinfeld. Any others?

Reference

Nosal, Andrew P., Elizabeth A. Keenan, Philip A. Hastings, and Ayelet Gneezy. "The effect of background music in shark documentaries on viewers' perceptions of sharks." PLoS one 11, no. 8 (2016): e0159279.