This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Credit: Prestel Publishing

I began flower gardening two years ago and discovered, to my surprise, that is is one of the most deeply satisfying, therapeutic activities I have ever tried.

These are some of the many zinnias I grew from seed started in roasting pans on my deck last year:

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

"Thumbelina" zinnias, which were supposed to get no higher than 15". My tallest hit 4 feet. Credit: Jennifer Frazer

I couldn't keep the two-tailed swallowtails and painted ladies off those flowers with a leaf blower. They were DETERMINED.

"Persian Carpet" and "Candy Mix" zinnias. Credit: Jennifer Frazer

Grow zinnias. If there's another flower that's as easy, rewarding, or as big of a butterfly trap, I'd like to see it.

Gardening has been a natural history gold mine. I've watched, enraptured, as a spider snatch a honeybee from mid-air and wrap it up in silk. Last year my Autumn Joy sedums hosted both a large colony of aphids -- along with ladybug eggs, larvae, and adults who feasted on the all-you-can-eat buffet.

Oh, and there was my five-foot garden bullsnake and rabbit-deterrence system Reggie, who crawled in off the prairie from time to time.

Reggie on patrol among the California poppies. Credit: Jennifer Frazer

If you care about biodiversity, a flower garden is a highly concrete thing that you personally can do to help preserve it. And now that I've done it, I understand why gardening is also a monk-approved, artist-approved, and physician-approved activity. It is one of the best hobbies you can do for both yourself and the planet.

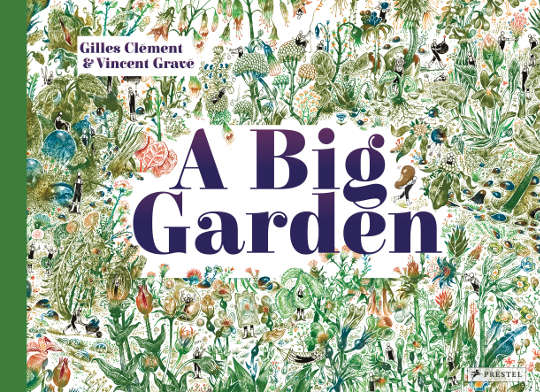

So it was with pleasure that I opened a review copy of A Big Garden (Prestel, $24.95)by Gilles Clément and Vincent Gravé, a book originally published in France and designed to pique children’s interest in this venerable and worthy activity.

The art is the show stealer here. Printed gloriously large-scale – A Big Garden is a BIG book, measuring 12" by 16 1/2" – it studies the garden month-by-month with a style that owes a great deal to the great early Dutch master of the bizarre, psychedelic, and whimsical, Hieronymous Bosch. It is wildly imaginative.

A tiny section of the artwork May in "A Big Garden". Illustration by Vincent Gravé. Credit: Prestel Publishing

Among my favorite books to look at as a child was a picture dictionary that named all the parts of a ship, a shopping mall, or a grocery store. Similarly, A Big Garden asks you to observe for yourself the smallest details -- both real and imagined -- in a garden passing through the seasons. As with Bosch works, studying the minutiae pays dividends. You might spot a morel mushroom rocket ship or a remote-controlled ladybug or a skiing sheep or a flock of bandit penguins.

That said, A Big Garden is a book with textual flaws. The ideas wander and the chapters lack cohesion. The writing itself is often weak and poorly translated. Some of the ideas are also deeply, deeply weird. However, weirdness is not in of itself a flaw – kids love weird, and trying to figure out what in the heck the author was thinking of and how it relates to the art and to gardening could provide both entertainment and exposure to the art of literary analysis.

This book performs one other valuable service. The latest edition of the Oxford Junior Dictionary omitted the words acorn, cygnet, heron, ivy, and nectar, replaced with blog, chatroom, and celebrity (and yes, I realize the irony of complaining about this on a blog). Little by little, children are becoming divorced from the natural world. Fewer and fewer are allowed to play outside unattended, even in places where they have access to nature. Without that time to explore and bond with nature, they often lose the visceral love of the natural world that is essential if we are to have any hope of protecting and preserving it.

The children also lose access to something deeper and more fundamental -- anxiety relief, learning, and creativity. A garden may be a space that parents feel more comfortable letting their children explore, and in which children can reap many of the benefits that come with plant, insect, and animal face time.

A Big Garden is not for everyone. But for those who enjoy science and art, who like having their minds stretched, and who like all things small and whimsical, it is certainly worth a look.