This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Americans are casting their votes today in what will be a momentous election. It has been a long and emotionally draining ten months where we as a country have had to come to terms with some hard truths about our neighbors' views on race and sex and class. We live in a time where sharing our opinions has never been easier, but the price of sharing those opinions has been general divisiveness in households and between good friends and colleagues. If anything, this election has perhaps caused us to consider the people in our networks and question the integrity of those connections.

Before the coming of social media, yard signs were one of the ways support for candidates manifested. The destruction of these signs has also been a means of protest. The American history of the political yard sign may date back to 1824 when John Quincy Adams had signs printed for his presidential run. Our current wireframe version seems to have originated in the sixties. However, the legacy of this kind of political propaganda is much older.

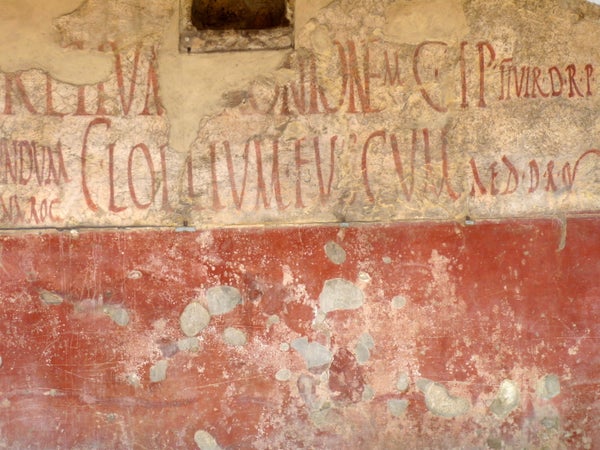

Ancient Romans have left us with a few excellent examples of using posters to publicize viewpoints that were important to them. The outer walls of the houses uncovered at Pompeii, for example, are covered in scribbles that serve as house signs, inventories, notices of markets days, rentals, and missing animals or items. The front of the home of an important citizen advertised public games that the family would sponsor, likely a testament to their wealth and status.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Roman graffiti also tells us about municipal politics. The simplest notices were only one or two words in Latin (e.g., Casellius aedile) or just a name. Others were decidedly more complex. They specified qualifications and were suggestive of broader endorsements:

"I beg you vote for C. Julius Polybius for aedile. He makes good bread."

"I beg you vote for C. Gavius Rufus for duumvir. He is useful to the state. Vesonius Primus recommends him." (M. Vesonius Primus has been identified as living in the so-called House of Orpheus. He ran the fullery next door and so would have been a person of some significance.)

"I beg you to vote for M. Pupius Rufus for duumvir with judicial authority; he deserves public office. Mustius the fuller supports him and whitewashes (here), the sole writer without the other members of his guild."

"Primus and his household support Cn. Helvius Sabinus for aedile."

"The fruit sellers incorporated together with Helvius Vestalis recommend M. Holconius Priscus for duumvir with judicial authority."

You get the idea. So widespread was the practice of public notices that some Romans inscribed hexes on their walls. For example, on a monument near Rome an inscription reads, "Inscriber, I beg of you to pass this monument by--if ever any candidate's name shall be written on this monument, I hope that he will be defeated and never carry an office!" Clearly, we have the Romans to thank for the "Post No Bills" stamps that adorn the barriers around construction sites.

The jury is out on whether lawn signs have a real impact on voters (see here, here, and here), but at a minimum they allow people to take a stand on an issue or person that they feel represents them. They can give people the courage to go public with an unpopular opinion and give others something to respond to in the public theater of participation, whether that means a sign of their own or stealing or destroying someone else's sign. In this regard, lawn signs continue a tradition that we can see traces of in ancient Rome. It sets the stage for public discussion and disagreement. And if nothing else, they tell you a little bit about your neighbors

Have something to say? Comments have been disabled on Anthropology in Practice, but you can always join the community on Facebook.

--

Referenced:

Brewster, E.H. (1944). "Poster Politics in Ancient Rome and in Later Italy." The Classical Journal, Vol. 39(8): 466-483.

--

You might also like:

Why did pirates fly the Jolly Roger?

Unmasking the truth in caricature

Our public affair with food porn

Tracing the Trickle-down in Roman Recycling

--

Image Credit: Mirko Tobias Scafer