This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

No matter how far human society progresses, there will always be criminal acts of violence. While many of the crimes have stayed the same, methods of self-defense looked a little different one hundred and fifty-four years ago.

The 1857 issue of Scientific American featured an invention aimed at preventing strangulation, the Anti-Garrote Collar. Garrote, a word with Spanish origins, refers to the act of strangling or to the tool used to strangle someone. According to the article, the crime went something like this: “Mr. Garroter steps softy up behind his victim, and chokes him with the rope, while Messrs. Accomplices abstract his portmonnaie [wallet], his watch, gold studs, gold sleeve buttons, horn-handled jack-knife, wooden pocket combs, quill toothpicks, short lead pencil, a choice recipe copied from the Scientific American, and all other ornaments which people worth garroting are supposed to always carry about them.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

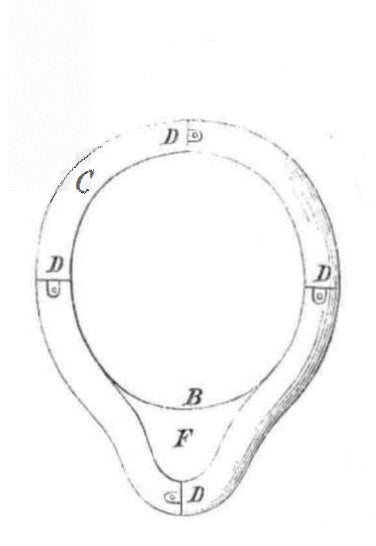

Protection from these attacks was thought to require some form of collar, and previous attempts to fashion something included a collar with projecting iron prongs and one that housed a backwards-facing pistol that would discharge in this face of the attacker who came from behind when pressure was applied to the front of the neck. Mr. C. Colne of Philadelphia invented this particular collar made of thin iron and consisting of upper (A) and lower (A’) parts. A groove (B) ran around the middle of the collar and opened in the front to a knife blade (F) that would cut the garroting rope when it was placed about the neck. The collar folded over at the top (C) and protruded at the chin (E) in order to hide the blade. It consisted of four separate pieces (D) that were hooked together and could be “taken apart and carried in the pocket to be put on when required.” The article fails to mention specific “required” situations, but I would guess they included walking alone through dark alleyways and publicly reading a copy of Scientific American.

The anti-garrote collar seemed to make up in efficiency what it lacked in comfort. It was said to be “probably as comfortable as the stiff stove-pipe hats which we so long have suffered.” That may be why self-defense techniques have changed over the years…that and the perpetual loss of neckties caused by forgetting to remove the collar when dressing.