This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Growing up, my brother and I spent many summer days at my grandparent's house. Sometimes, my grandma would bring out a 1960s Westinghouse record player that belonged to my aunt and let us play records from artists we had never heard of. While dancing to Lesley Gore and Smokey Robinson served up hours of fun, the admonition to never touch the needle on the record player always left me slightly on edge. I inherited this same record player and remain nervous and curious about its needle, which now produces static and popping noises whenever a record is played. Finding an article on phonographic needles in Scientific American has led me to appreciate the history behind the point.

At the time of this article’s publication, July 5, 1919, the phonograph had only been a household item for 10 to 15 years. While it was still considered a novel invention, persons such as F.D. Hall of Chicago began looking for ways to improve upon it—specifically its sound quality. The phonograph made “tinny” and “harsh sounds,” and was also described as being “unduly loud.” Further, the metal needle often wore down the records after a short while.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Ruminating on these matters, F.D. Hall asked himself, “Might not something be done at once to better the connection between the soundbox and the record? The tone must somewhow be improved; could it not be done by substituting, for the metal stylus, some fibrous substance of less natural harshness?” His first thought was wood, but after experimenting with several types he was instead led to a grass—bamboo. Bamboo was ideal for a needle because of its tough cellular composition and smooth, glossy exterior.

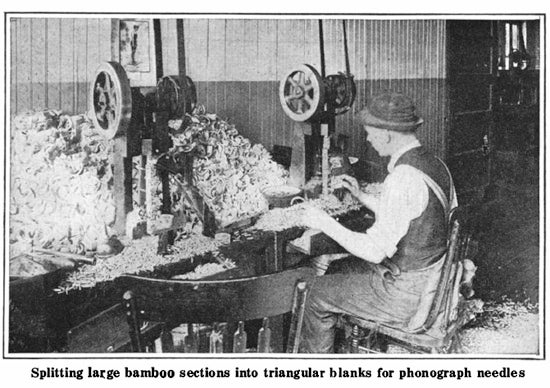

Bamboo poles that were used in the patented manufacturing process had to be 20 feet long, 2 ½ to 3 ½ inches wide, and could not have any exterior damage when they arrived from across the ocean. The poles were then sawed into 1-inch sections that were subsequently split in half.

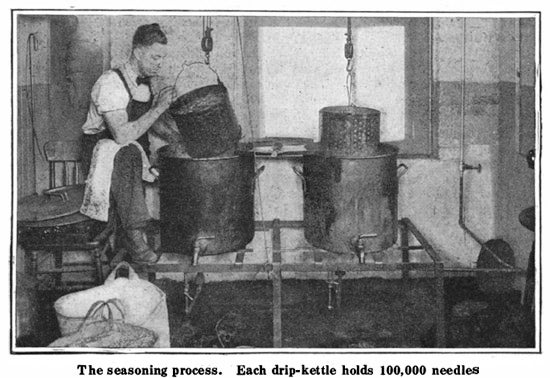

These halves were further split into crude needles by a machine that split 125 to 180 per minute. During this process, the inner part of the shoot was detached, leaving only the hard outer shell. Next, the sap within the cells of the bamboo had to be removed and replaced with essential oils and waxes to help protect it from moisture. Then, the needles were placed into a drip kettle and lowered into a “scientifically prepared mixture” heated to 340 degrees Fahrenheit.

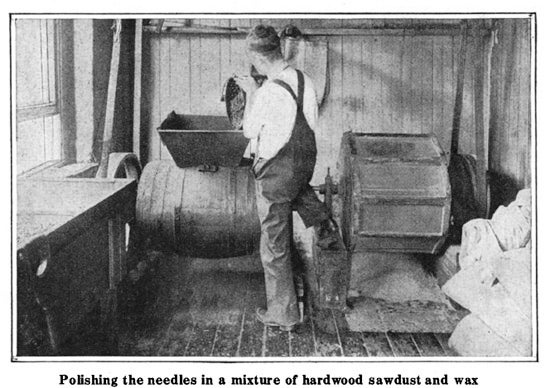

Next, needles were placed in tumbling barrels full of coarse hardwood sawdust in order to be cooled and polished.

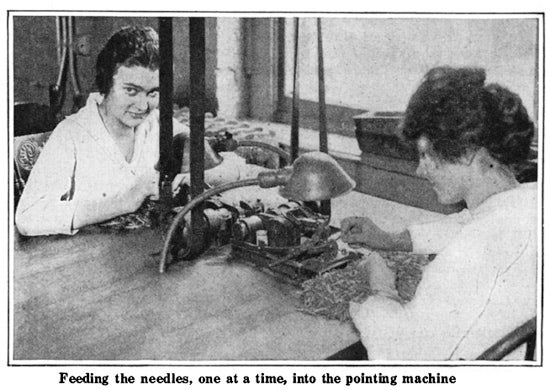

After this, the needles were pointed by hand.

“The prism-shaped pieces are inserted into a triangular bushing on a cutting machine of original design, placed so as to insure a perfect point running out to the cortex side of the bamboo.” Lastly, the needles were inspected, counted, and packed for shipping.

Other materials used for phonograph needles over the years have been diamond, sapphire, steel, copper, tungsten, and cactus needles. Today, most are made with diamond. While bamboo needles are no longer used, you can actually find and purchase them online. Bamboo needles may be a great way to get that authentic vintage sound and are the perfect way to impress your audiophile friends.