This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

The issue presents two innovations from a century ago: both of them are armored vehicles. But one variety was (and is) only somewhat useful, and the other type has been winning battles for a century.

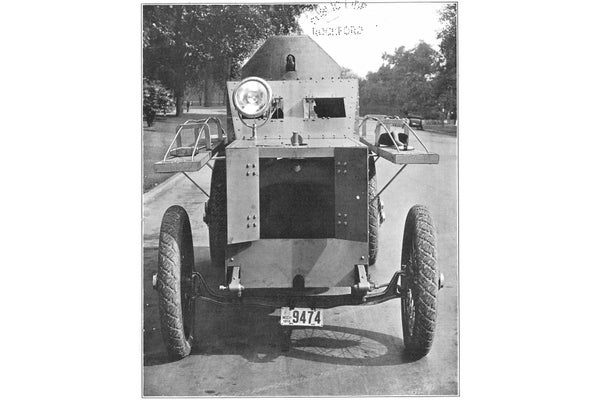

The cover image on this issue of Scientific American presents the first armored vehicle made for the United States: the King Armored Car. Two experimental units were built in 1915 and eight were ordered by the U.S. Marine Corps in 1916. They were not used in World War I, but some saw service later in Haiti and Santo Domingo. The concept was sound, and in fact a variety of armored cars had occasionally been employed for a decade in other countries. But such vehicles are limited by the need to travel on wheels: they need functional roads or city streets, or flat, dry ground. The writer of 100 years ago was sanguine on the usefulness of armored cars on the Western Front:

“With the destruction of everything resembling a road in the neighborhood of the fighting lines, the light armored automobile was put out of the running, as its ability to negotiate rough ground is decidedly limited, and it could by no means surmount shell craters, much less jump trenches.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The armored car was more useful in other theaters of operation:

“On the Eastern front, however, the operations were of a more open character, and soon we heard of the excellent service the armored car was doing there, where in some cases Russian cars broke through the opposing lines, and, opening an attack from the rear, contributed largely to important successes. Then came the Egyptian [Mesopotamian] campaign, and here again, in open country, the armored automobile played an important and valuable part in breaking up scattered bands of opponents, maintaining telegraph lines and carrying dispatches through long stretches of hostile country.”

This particular armored car, however, has the same drawbacks as most early models: the chassis was a civilian car made by King, with light plate armor bolted on and a turret added. The additional weight made the machine heavy, cumbersome and unbalanced.

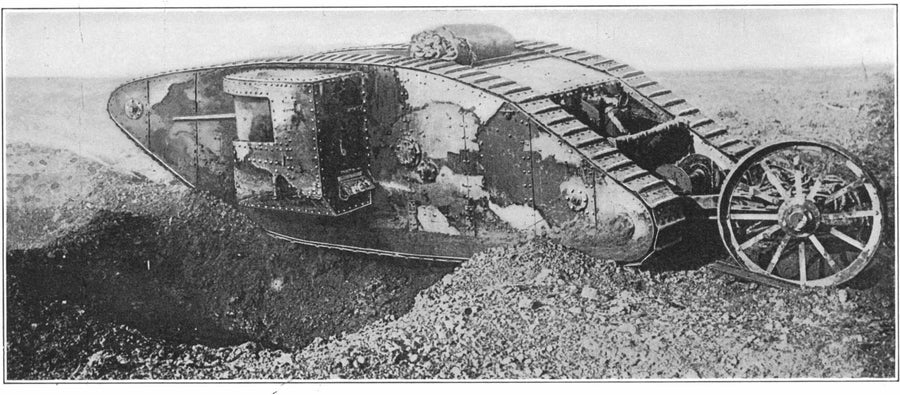

British tank used in the Battle of the Somme, 1916, painted in camouflage colors. Even the most primitive early tanks could be highly useful. Credit: Scientific American Supplement, January 6, 1917

The other armored vehicle in the issue is a tank: in this case a British Mark I “male” tank (armed with machine guns and 6-pounder guns). The specific tank pictured may have been used in the battle of Flers-Courcelette during the Somme offensive in 1916. The concept had been alive for centuries, but it was only in 1916 that a workable version, powered by an internal-combustion engine and driven on a continuous linked tread instead of wheels, gave the machine the ability to crawl over any terrain, carrying soldiers and heavy weapons with relative safety into the thick of the fighting. That ability has made this invention decisive in land battles for a century (and has been sometimes useful for tyrants keen on suppressing dissent). In 2016 the tank is still useful but is now more vulnerable to newly designed and highly sophisticated anti-tank weapons.

Back in 1916, there was some skepticism in the earliest press reports:

“ ‘I watched the great things maneuver about the field, grotesque and unspeakable; and at each new antic which they performed, each new capacity which they developed, one could do nothing but sit down and laugh till one's sides ached. Were they only a preposterous joke or were they a serious contribution to modern warfare?...’ ”

But the article also contains a very neat summation of the value of armored, tracked, heavily armed vehicles:

“More recently, one of the most sensational developments of the war was disclosed by the unexpected advent of the British Land Ships, as they are officially rated, but more popularly known as the ‘tanks,’ and thus was the armored car reincarnated in a surprising, but vastly more powerful and effective form, for it is not only capable of being operated over what has heretofore been considered impossible surfaces, but it is also proof against the attacks of anything short of powerful field guns, and is itself armed with heavier and more efficient weapons than any of its more agile predecessors.”

This particular tank, according to the Imperial War Museum in Britain, was “a hulk”, meaning it either broke down or was partially destroyed and abandoned. The photograph was taken by Lieut. William Ivor Castle, who worked as one of Canada’s official war photographers from August 1916 to June 1917, when he was wounded (gassed) near the Somme.

A Note on Camouflage

In 2016 we are well used to “disruptive pattern material” or “camouflage”; a century ago, such details apparently needed an explanation:

“Most of the variegated effects are the result of the system of ‘protective painting’ which, has heen adopted, for all of the tanks are irregularly painted in browns, greens and yellows that harmonize with the landscape and make them difficult of detection at a short distance. This method of deceptive coloring, by the way, is by no means new, but has been extensively applied to field guns and other exposed objects in the field.”

-

Our full archive of the war, called Scientific American Chronicles: World War I, has many articles from 1914–1918 on technical developments in the First World War. It is available for purchase at www.scientificamerican.com/products/world-war-i/