This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Wartime food shortages in Germany in the winter of 1916–1917 were terrible. The civilian population called it the “turnip winter,” a bitter nickname, given the indignity of having to eat turnips, normally considered to be food fit only for cattle. Alexander Watson in his book Ring of Steel noted that “Germany teetered on the brink of starvation during the second half of the war.” The blockade on imports and exports imposed by the British (and enforced by the Royal Navy) at the start of the war in 1914 is mostly to blame. Some scholars argue that food was scarce but not critically so, but there’s an interesting statistic in a 2003 article by William Van der Kloot that shows the lack of food for people and cattle alike: the average weight of cattle at slaughter dropped from a prewar high of about 550 pounds to a low in 1918 of about 300 pounds.

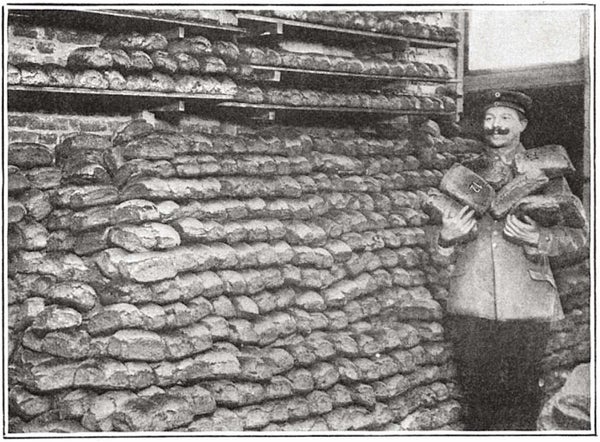

Against that background, there’s the hopelessly optimistic article from Scientific American written by American citizen, Albert K. Dawson, in Germany (while the U.S. was still neutral) and published 100 years ago today: “Economic Conditions in Germany (part II): A Great National Bread Trust.” There is a charming vignette to begin the tale:

“‘Your bread card please,’ says the waiter and at the same time deftly withdraws the plate of bread for which I am reaching. ‘All right,’ I say, ‘In a minute; let's have one of those rolls.’ ‘Card first,’ says he and moves the plate still farther back. Then follows a search which usually ends in my finding that I have left my bread card at home or in my other coat. This I explain at length, but to no avail. The waiters cannot be coaxed, frightened or bribed. Like the Chinaman who says, ‘No tickie, no washee,’ they stand firm on the rule, ‘No ticket, no bread.’ When relations with the determined waiter reach the point where the average American feels like taking the matter up with our Ambassador, it usually follows that the portly German across the table interrupts with ‘Pardon, mein Herr, but I see you are an American and do not understand our system. May I put my card at your disposal?’ And with a courtly gesture, like one offering another a cigarette, he hands his card across the table. I have gone through this performance not once, but dozens of times, and I have found that, if I argue long enough and loud enough, someone will always come around and offer me his bread card. From this the waiter detaches one of the 25-gram checks for which he then gives me one roll or one slice of bread.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

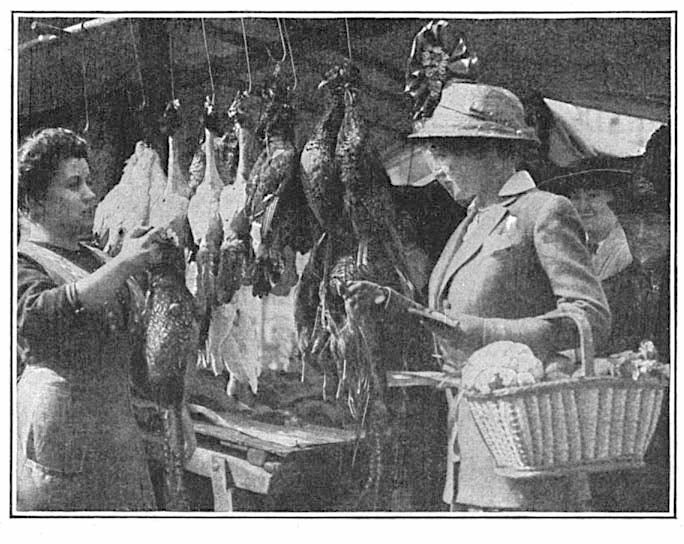

A meat market in Berlin, 1917: “game is cheaper than poultry.” The winter of 1916-1917 was called the “turnip winter” as starving civilians ate food normally fed to cattle. Credit: Scientific American, January 27, 1917

"Such are the workings of the German food system; there is enough for everyone and to insure each one's getting his share the card system is used. The price is fixed by law and the amount any one person can buy at one time is limited to his immediate need, thus making speculation out of the question.”

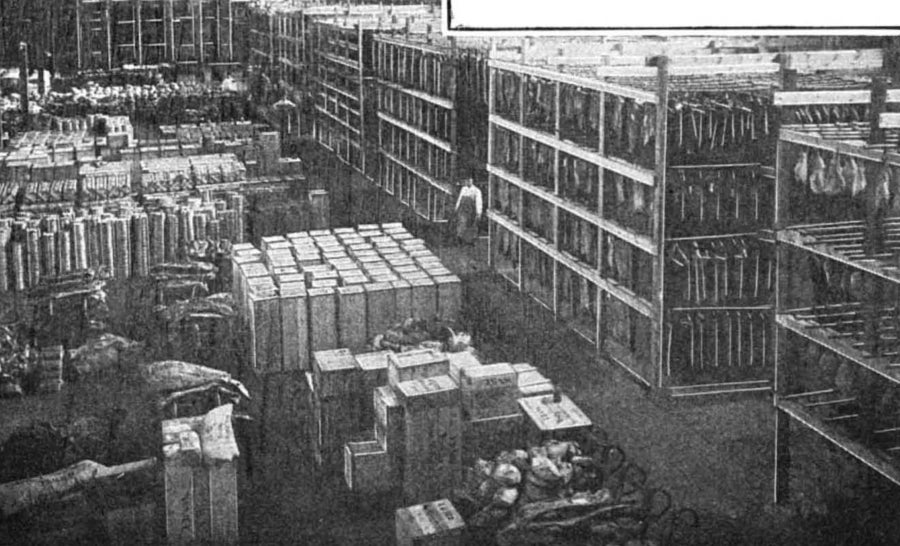

More descriptions and photographs by the author follow, of warehouses overflowing with food, and he “reveals” a government policy that sounds very thoughtful—except that nobody thought of it:

“At the beginning of the war, as a measure of precaution, the German government required every city of more than five thousand to put away in storage meat in some form to the value of eleven marks per head of population. This means that there is a reserve supply of meat stored away amounting to about thirteen pounds for every person in Germany. (About eighty-five per cent of the population lives in cities of over 5,000 and at the time these supplies were laid in 11 marks would buy fifteen or sixteen pounds of meat). This fact is not generally known. even to the mass of the Germans. I have never seen it published in any of their newspapers.

"The government has probably passed out word to the censor to keep it quiet so as not to cause public discontent. The above figures were given me by one of the men who is in the Central Department, which did most of the buying for the cities. Furthermore, this tremendous reserve was all bought outside of Germany so as not to disturb the home market. In order to convince me of these facts, he gave me letters which allowed me to visit the great warehouses and cold storage plants of the principal cities, where I could see for myself. I did not have time to visit them all; but the amount of meat I saw in storage was beyond belief. It comes in every form: Salted, smoked, dried, canned, pickled and frozen. One single cold storage plant just outside of Berlin contained 6,000,000 pounds of frozen meat which had been in storage since October, 1914.

"These warehouses are guarded night and day like the national treasury, and it was only with much formality and showing of passes that I was allowed to go in at all. Usually photographs were not permitted; but I was fortunate in finding an old friend in charge of this department in Hamburg, so there I was allowed to make photographs.

A warehouse in Hamburg, 1917, filled with “reserve provisions”—but it is not stated what provisions, or for whom, or for how many. Credit: Scientific American, January 27, 1917

"This particular municipality has not confined itself to the 11 marks per head prescribed by law; but, with the foresight of a great commercial city, she has laid away several million marks worth of other provisions. According to the guide books, Hamburg has 62 miles of warehouse docks. I did not look into every one, but I saw enough to convince me that Hamburg would be the last city to suffer from hunger.”

Perhaps Hamburg was the last city to suffer from hunger, but the meat ration in 1916 was a third of what it was prewar, and Erik Sass of Mental Floss noted that in August 1916 “the major port city of Hamburg was rocked as hungry workers rioted” and Dr. Helen Boak notes, “In August 1916 a group of soldiers’ wives wrote to the Hamburg Senate demanding its support for a peace settlement: ‘we want to have our husbands and sons back from the war and we don’t want to starve any more.’” Six million pounds of meat would have fed the German army for two days on the reduced rations of 1916. It is a ridiculous fantasy to suggest that the government had the foresight to buy up foreign meat stocks to prepare for a long war when those in charge of the government were convinced the war would be short and sharp and wouldn’t last long enough for hunger and starvation to become the problem that it was. My view from 2017 is that the article is attempting to use a gullible journalist to suggest that the British blockade was ineffective, and therefore not worth enforcing, when in reality, the effects on the civilian population of Germany—especially the poor—were severe enough to cause at least 400,000 deaths from starvation.

External Sources:

Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I. Alexander Watson. Basic Books, 2014.

“Ernest Starling’s Analysis of the Energy Balance of the German People During the Blockade, 1914–19.” William Van Der Kloot In Notes and Records: The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science, Vol. 57, No. 2, May 22, 2003. http://rsnr.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/57/2/185

“WWI Centennial: Starvation Stalks Europe.” Erik Sass in the online magazine Mental Floss, August 24, 2016.

http://mentalfloss.com/article/85224/wwi-centennial-starvation-stalks-europe

[Sass, by the way, writes an exceptionally well researched weekly post about events in World War One exactly 100 years earlier]

“Food and the First World War in Germany.” Dr. Helen Boak on the website Everyday Lives in War from the University of Hertfordshire, April 29, 2015. Quoted from “Der Krieg der Frauen 1914-1918: Zur Innenansicht des Ersten Weltkriegs in Deutschland” by Ute Daniel, in Keiner fühlt sich hier mehr als Mensch…’. Erlebnis und Wirkung des Ersten Weltkriegs” edited by Gerhard Hirschfeld et al. (Essen: 1993), p. 131.

https://everydaylivesinwar.herts.ac.uk/?p=435

-

The views expressed are those of the author and are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

Our full archive of the war, called Scientific American Chronicles: World War I, has many articles from 1914–1918 on economic aspects of the First World War. It is available for purchase at www.scientificamerican.com/products/world-war-i/