This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Tanks were first used in battle on September 15, 1916, in the latter stages of the Somme offensive, at the battle of Flers-Courcelette. There were a small number of machines and after a few had broken down or become lost, perhaps 27 reached the German front lines. A few of these tanks were successful enough in attacking the German trenches to show that such inventions could break the deadlock of trench warfare.

The previous week’s issue of September 30, 1916, had talked about the new weapon:

“Strange tales are coming to us from the battlefields of northern France. We would almost believe that our old friend Baron Münchausen had come to life had ont the extraordinary developments of the present war prepared us to accept the wildest yarns as possible. War correspondents have been telling us of a huge British machine that hurdles trenches and shell-holes, that prefers to smash through a tree rather than pass around it...of course, these stories have been colored by the highly-stimulated imagination of writers, but, after making due allowances, the fabulous antics of these new juggernauts come within the limits of possibility.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

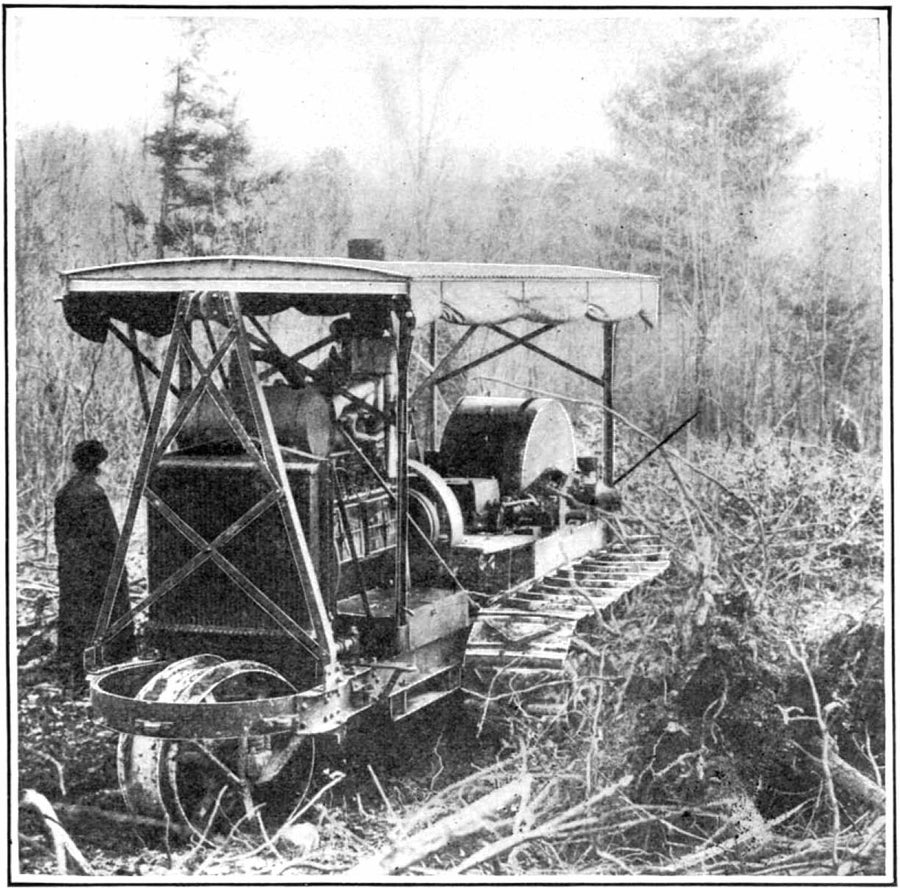

A civilian tractor, using tracks to crush over and through scrub, shows how the editors in 1916 thought the new tanks would be propelled. Credit: Scientific American, October 7, 1916

But censorship of new, successful weapons was strict: few military or civilians knew what these machines looked like: the new weapons were not even yet called “tanks”: In the discussions of the article in the October 7, 1916, issue they were referred to as “armored armadillos” and “armored tractors”:

“Now, as to the form, size, weight and power of the armored tractors used by the British in the present Somme offensive, it is to be noted that no definite information has been allowed to pass the censor regarding these features; so that what we have to say in this regard is a matter of mere speculation.”

The article went on to attempt to synthesize what little was known about such machines. Armored cars, first envisioned by Leonardo da Vinci as far back as 1487, were built and used in the earliest months of the First World War. But wheeled vehicles were limited—they could only travel on roads or hard, dry, flat ground (for instance, the deserts of the Middle East). The most useful armed and armored fighting vehicle is one that can go across the same ground that infantry needs to cover; a tank does so with the use of treads around its wheels.

It was well-known by 1916 that heavy tractors with treads could cross the roughest of ground. One of the images shown in the article is a civilian tractor crushing its way through scrub (possibly in the Everglades?). Scientific American had already published an article on military testing of treaded vehicles titled “The ‘Caterpillar’ Tractor” on May 16, 1908, and another article on March 6, 1909, titled “A Gasoline Caterpillar Traction Engine” that discussed that mode of locomotion over broken ground. It would have been easy to extrapolate what was known about the use of tracks on tractors to assume that the armored machine in question would run on some kind of tread system. (Incidentally, the ancestor of the very successful company that today makes Caterpillar earth-moving equipment first applied for their trademark in 1910, after these issues were published.)

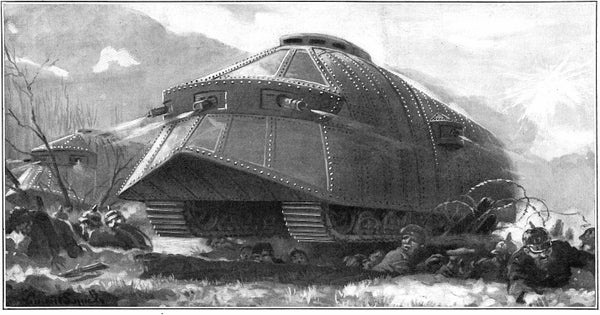

The armored exterior that we show has hints of the illustration from “The Land Ironclads,” a short fictional story about tanks in trench warfare written by H. G. Wells and published in the Strand magazine in December 1903. But the exterior form of the new tanks in this particular issue seems largely based on a design submitted to the British government—and rejected: “We present drawings of a design for a military tractor for use against the trenches, which was made in response to a request from Great Britain to a Western firm, for plans of a machine suited to the purpose. These plans were submitted to the Naval Munitions Board in London.”

Pian and section of an “armored tractor” design, submitted to the British government and rejected. The engine here looks quite miniscule. Credit: Scientific American, October 7, 1916

The article wraps up with assessments (or just propaganda, really) by the Germans and the British, and speculation on the future of warfare that accurately predicts the massed-tank battles two decades later in the Second World War:

“What part these machines are destined to play in the later stages of the war is a matter of pure speculation. The British speak of them as a great success; Berlin, naturally, describes them as being a complete failure—unwieldy, slow, and liable to break down. If they are successful, Germany is certain to come back with something of the same kind; and, if so, we may see squadrons of these mechanical armadillos maneuvering against each other in the open field—truly a sight for the gods.”

In upcoming entries from the Archive, we’ll have some more information and images of British and French tanks that were developed and deployed in 1916.

-

Our full archive of the war, called Scientific American Chronicles: World War I, has many articles from 1914–1918 on the technology of warfare on the Western Front in the First World War. It is available for purchase at www.scientificamerican.com/products/world-war-i/