This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

This article in Scientific American from 100 years ago today takes a look at the vast number of prisoners interned in Germany and Austria-Hungary.

The information on the prison camps is interesting, but the propaganda presented by the article is fascinating. The treatment of prisoners became a central theme in the propaganda of all sides fighting in the war: enemy conduct that could be portrayed as awful or uncivilized lent weight to a posture of moral rectitude. As Heather Jones pointed out, “belligerents fiercely defended their prisoner of war treatment policies throughout the conflict” [see bibliography below].

It’s quite a pleasant article: being a prisoner doesn’t seem so bad. But the well-ordered prison camps presented here only emerged after a year of warfare: the original belief had been that the war would be over quickly, and the scale of the fighting, and the vast number of prisoners that resulted, were not anticipated. Early camps were haphazard and disease-ridden affairs, and it took a couple of years for the camp system to start working decently. And of course there’s no mention of the camps near the front lines where prisoners under harsh discipline were forced to work on military fortifications. In the article there’s a healthy dose of stereotypes of the day, including a nod to the popular idea that Russians were backward, dirty peasants. There’s a broad hint that Germany favorably viewed the religion of Islam (a frequent theme in German propaganda, given that of the 400 million people under the sway of the British Empire, perhaps a quarter were Muslim and were actively courted by the Central Powers).

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The author was a well-known photographer, Albert K. Dawson, who was quite well-known for his images from the battlefields of World War One. Perhaps he was less practiced as a journalist. The article presents the idea that “Under international law a prisoner of war cannot be obliged to work” and says that those that worked did so to escape boredom and to earn a tobacco allowance. Yet by 1917, with so many men taken from fields and factories to fight in the army, prisoners of war such as those depicted in these images were being treated as a vital component of the domestic labor force. The historian Alexander Watson has recently pointed out [see bibliography below] that in Germany “by August 1916 [prisoners] accounted for around 14 per cent of workers in the Ruhr coal industry” and by the end of the war “1.5 million prisoners were spread across 750,000 German farms and firms.”

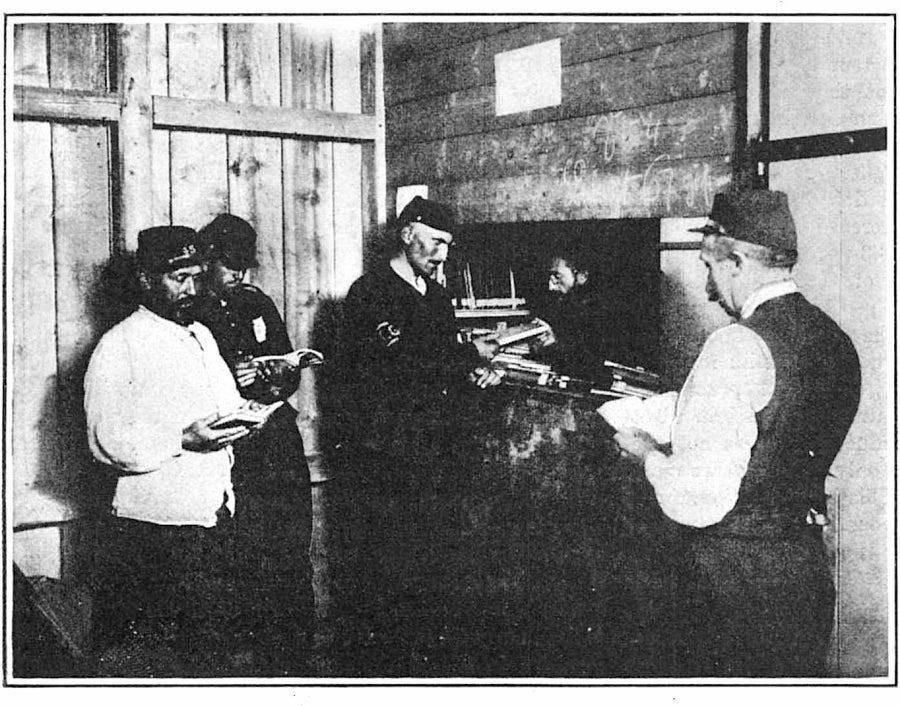

The library at the POW camp, 1917. The books are “received in their packages from home.” It all sounds quite civilized. Credit: Scientific American, January 20, 1917

Here’s some of what we said a century ago:

“Over three million prisoners are in the hands of Germany and her allies at present. This means more than the population of Indiana. It also means more men to feed, clothe, guard and care for than are found in the entire Dominion of Canada. Add to this the fact that they are not all of one race or language, but represent every race from the Equator to the Arctic and speak every language in current use to-day. Complicate this still further by having them of different religious beliefs and you will get some idea of Germany's problem of what to do with her prisoners of war. The Russian prisoners comprise the largest single group, and number about a million and a half. They are the most tractable of prisoners, simple-minded and obedient, accustomed to plain food and hard work, and to be counted as an asset rather than a liability to Germany, for they are doing most of her farm work at present. Without this Russian labor Germany could never have harvested her crops this year. They are sent out in parties of twenty-five or thirty to each village with one guard to look after them; They live with the villagers and seem to get on very well. Many of them have already married German peasant girls and it is said that fully half a million of them will remain permanently in Germany when the war is over.”

“Next in number come the Frenchmen, always good natured and smiling and according to the German authorities the easiest prisoners to handle. Among them are found skilled laborers, mechanics and professional men but not so many farmers.”

“The prison near Berlin where a large number of these odds and ends of humanity are cared for has been dubbed “The Royal Zoo.’ ”

“Under international law a prisoner of war cannot be obliged to work; but there is nothing to prevent his captor from inducing him to work by a reward of some sort. Thus we find thousands of French and English working in the shops and factories of Germany; as much, perhaps, to escape the ennui of prison life as for the small pay and tobacco allowance they receive. They are very careful not to work on any product which could be used as a material of war. Thus we find them building highways and public works, working in book binderies, factories making agricultural instruments, furniture and toys, and in establishments making women's clothing and shoes; but never making anything which could be used or worn by the men in the field.”

“Running water for washing and drinking is supplied each barrack and there is always a common bath house and laundry for the entire camp. This has shower baths, tubs and hot water and the men can go at any time to bathe and wash their clothes. The prisoners are obliged to take at least one bath a week, but this rule does not have to be enforced on the English and French; they wash as a matter of course. It is only the Russians and Orientals who must be lined up once a week, much against their will, for the Saturday bath. The Russian peasant can see no sense in bathing at any time, and the idea of letting quantities of water come in contact with his skin in winter time is simply suicidal to him. A company of Russians being marched to the bath house under guard on a winter day is always a source of fun to the English and French, because, judging by their expressions, one would think they were going out to be shot instead of washed.”

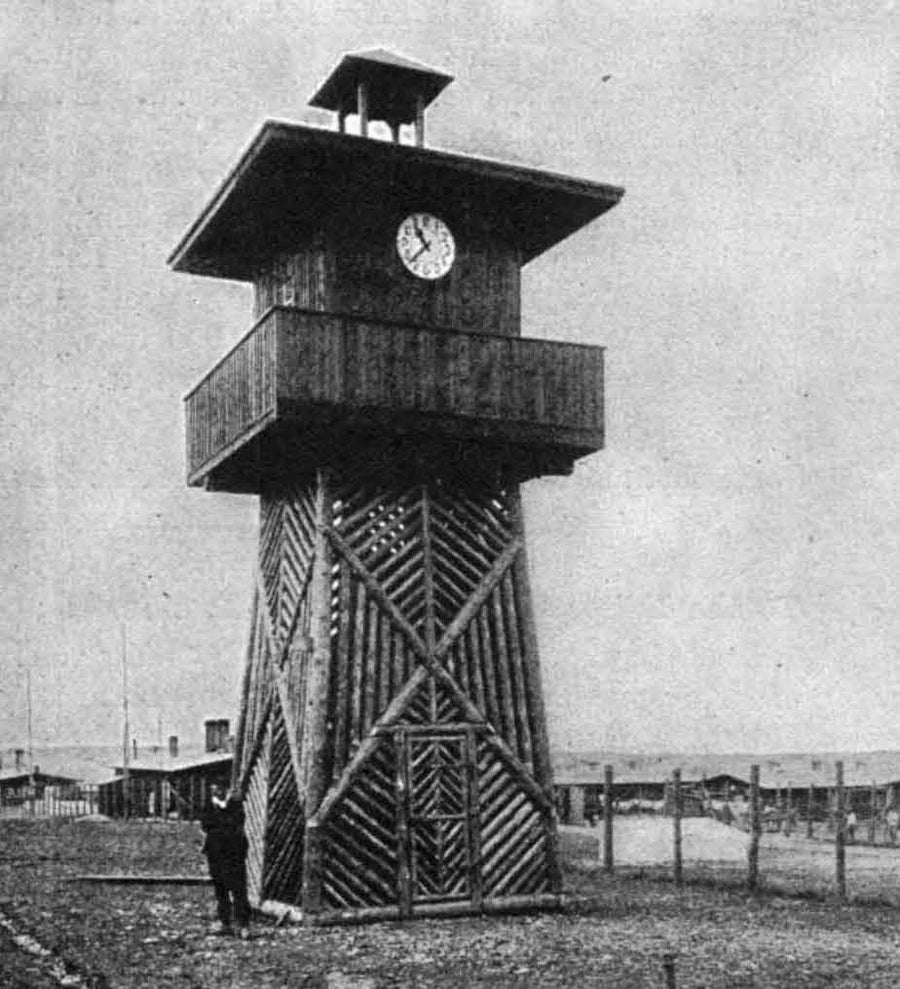

“The prison clock tower, designed by an architect among the men and built by the prisoners themselves.” Possibly from the Mannheim POW camp, 1917. No word on whether the clock actually worked. Credit: Scientific American, January 20, 1917

“Each prison has an empty barrack room or a large tent set aside as a church. Here services are held each Sunday by the prisoners themselves. In one of the camps housing a great many Mohammedans [the common term in 1917 for those adhering to the Muslim faith], a mosque has been erected in true oriental style, including the minaret from which each day at twelve the Hoja (priest)[sic] calls the faithful to prayers.”

Further reading on a subject that has been sparsely covered by the popular press and by historians:

“Prisoners of War.” Heather Jones. This and other fine articles by Dr. Jones of the London School of Economics are available free online from the International Encyclopedia of the First World War: http://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/prisoners_of_war

“Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I.” Alexander Watson. Basic Books, 2014. A rare English-language book on the home front of the Central Powers in World War One.

Original material from the International Committee of the Red Cross is available at http://grandeguerre.icrc.org/

-

Our full archive of the war, called Scientific American Chronicles: World War I, has many articles from 1914–1918 on various aspects of the First World War. It is available for purchase at www.scientificamerican.com/products/world-war-i/