This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

In 1917 modern armies needed modern weapons, and lots of them. The issue of Scientific American from 100 years ago celebrates the foresight of a group of businessmen in making a profit from the desperate need for arms in Europe.

“Strikingly typical of ‘impossible’ things made possible is the story of how a group of American businessmen, appreciating the importance of the machine gun in modern warfare and foreseeing the coming big demand for this class of weapon, conceived a giant industry devoted entirely to the manufacture of machine guns. Not to be daunted by the numerous industrial problems involved, which were made all the more difficult by the abnormal industrial conditions obtaining during the year just elapsed, these men have worked out their plans to a signally successful consummation in less than a year's time to the accompaniment of the chorus ‘It can't be done,’ from all sides. Toward the close of 1915 a group of men, headed by Mr. [Albert] F. Rockwell of Bristol, Conn., a well-known industrial leader of New England, announced their plans for the organization of a machine-gun industry on an unprecedented scale. Casting about for a type of gun that they could manufacture, the decision was made in favor of the Colt automatic gun, which has been the weapon of the United States Army and Navy for years past. Arrangements were soon concluded, with the Proprietors of the Colt automatic gun patents, whereby the new organization was authorized to manufacture this type of weapon under royalty”

“Despite a delay of two and a half to three months, due to the indecision of the Russians in charge of the initial machine gun contracts placed with the new organization, by April 29th the plant had ten guns finished. The most critical requirements and the severe inspection of the Russians were met successfully. Then the quantity production methods were gotten under way, with the most improved machinery and with personnel keyed up to the highest pitch engendered by high wages, bonuses, good fellowship and welfare work. By leaps and bounds the production rose to 160 guns per day, followed shortly afterward by the present output of 200 complete and perfect guns per day.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

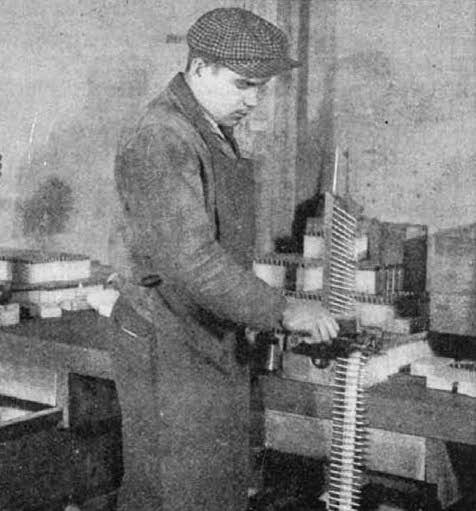

Loading ammunition belts for testing the 1917 Colt-Marlin machine gun. Credit: Scientific American, January 13, 1917

The Colt model 1895 “potato-digger” machine gun was considered obsolete as an infantry weapon by 1917, and had been superseded by the reliable Vickers water-cooled heavy machine gun or the lighter and more versatile Lewis machine gun. Colt sold the rights to manufacture this gun to a syndicate led by Albert F. Rockwell who had just bought the Marlin Firearms company. The company produced a large number of machine guns during the war, including those for export trade to Russia and Italy. The Colt-Marlin version of 1917 incorporated upgrades to the design; the new and improved model was used extensively on aircraft and tanks.

A wider moral and political question was raised during the war and remained afterward: Did arms manufacturers help push the United States into joining the Great War as a combatant because of a desire to profit from war production? It was a lingering question; 16 years after the war ended, the U.S. Senate set up the Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry, chaired by Senator Gerald Nye (Republican from North Dakota). The committee worked from 1934 to 1936; their report did not present evidence that arms manufacturers had conspired to drag the country into the war, but it did echo increasing public sentiment against the “merchants of death” (an epithet that originated in a book title from 1934).

The views expressed are those of the author and are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

Our full archive of the war, called Scientific American Chronicles: World War I, has many articles from 1914–1918 on industrialism in the First World War. It is available for purchase here