This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

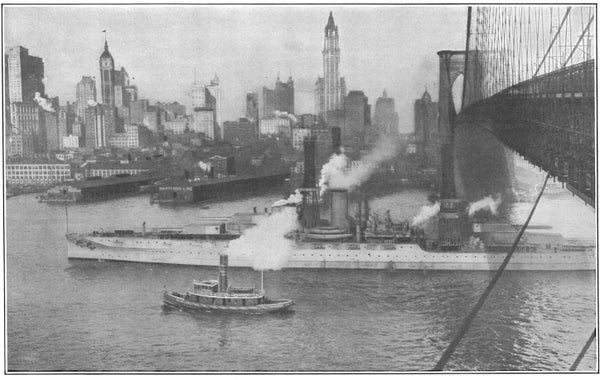

The cover story from 100 years ago today shows the battleship USS Arizona leaving the Brooklyn Navy Yard and steaming down the Hudson River under the Brooklyn Bridge. At that moment, the ship was one of the mightiest battleships in the world and a symbol of modernity that would herald America’s place as a major naval power.

Unfortunately, the early symbolism didn’t match the ship’s real-life history.

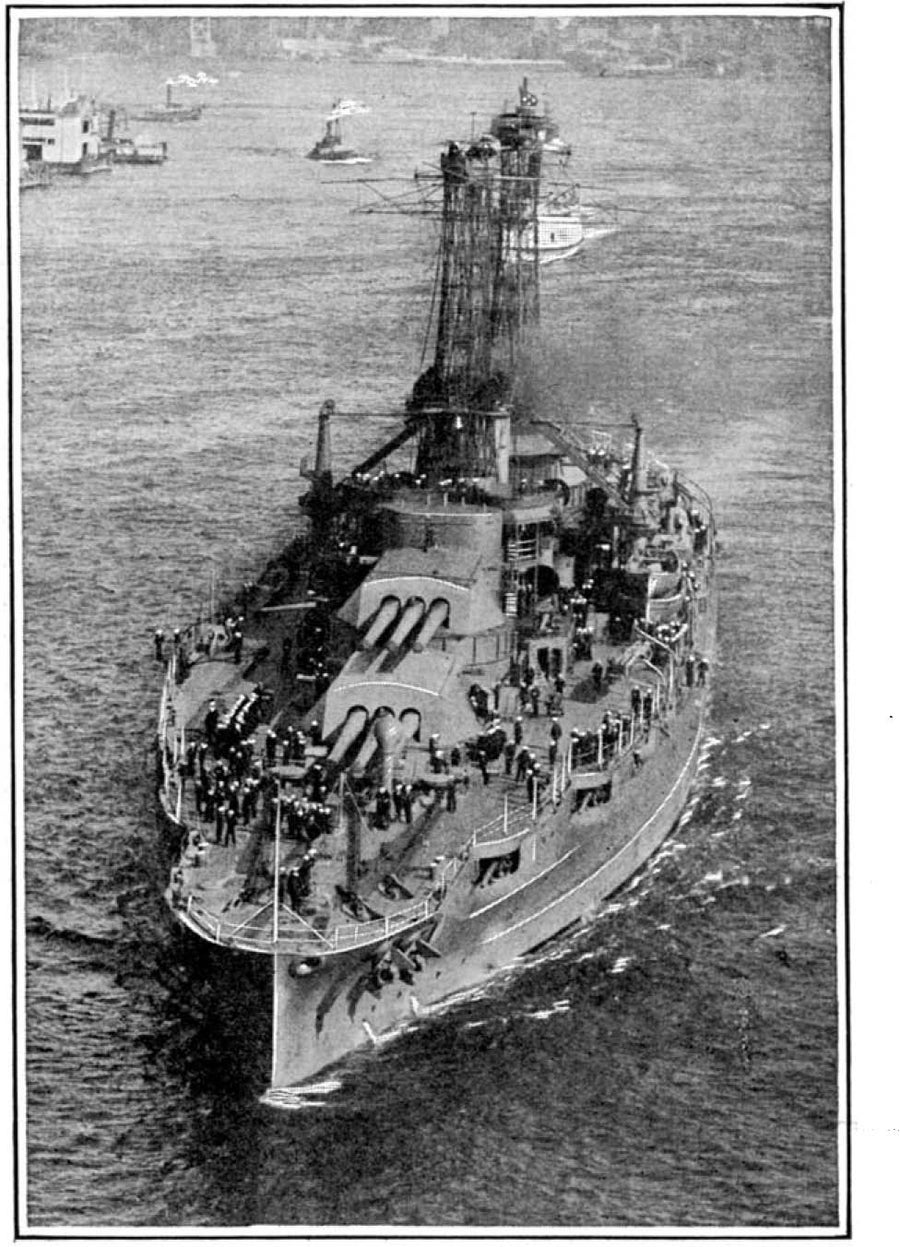

Sister ship to the USS Arizona, the USS Pennsylvania, showing the forward three-gun turrets mounting 14-inch guns. The arrangement of guns was somewhat outdated by the time the vessel was launched: the most modern ships had more powerful guns but fewer of them. Credit: Scientific American, October 28, 1916

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The modern technology of the ship may have been its greatest weakness. The U.S. Navy had opted for oil as a fuel for its battleships, as opposed to the traditional coal, starting with the U.S.S. Nevada, which first started building in 1912. Oil packed in more energy for the weight and volume, it could release that energy faster and more efficiently, and it could be moved onto and around the ship with pumps and pipes much more easily than the slow, clumsy, laborious work of stokers who had to shovel chunks of coal around manually. In 1912 the British Royal Navy had decided the same. Yet when war broke out, the supplies of oil from Persia (Iran, Iraq) were cut off, and at the height of the war, German submarines became quite successful in sinking oil tankers bringing oil from America and Mexico to the Allied navies. As Daniel Yergin noted in “The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money and Power (Simon & Schuster, 1991),” fuel was in critically short supply: “by the end of May 1917 ... the shortfall in oil supplies was constraining the mobility of the Royal Navy. So serious had the situation become that it was even suggested that the Royal Navy stop building oil-driven ships and go back to coal!” In America, too, demands for fuel (coal, oil) for factories and cars was skyrocketing, as was its cost. With such shortages, the large battleships, with no large ships to fight against, and useless at confronting the submarine menace, were a liability given how much fuel they burned up. The USS Arizona was kept at home for the duration of the war, and only emerged after the war was over to escort President Wilson to the Paris Peace Conference.

You have heard of the USS Arizona, unfortunately. Most people do not know its World War One history, but as a symbol of American sea power it was targeted on the first day of America’s involvement in World War Two, when it was sunk by a Japanese bomb in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The hull still lies on the seabed in the harbor as part of a memorial to the lives lost on that day.

-

The views expressed are those of the author and are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

Our full archive of the war, called Scientific American Chronicles: World War I, has many articles from 1914–1918 on technological developments in the First World War. It is available for purchase at www.scientificamerican.com/products/world-war-i/