This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

I'd like to imagine that an intense passion for sailing coupled with a severe case of hydrophobia were what compelled Mr. J. A. Aspinwall to invent the Sail Wagon, featured in the June 14th, 1884 issue of Scientific American. Or perhaps he just had enough foresight to design an ecofriendly and cost-efficient vehicle.

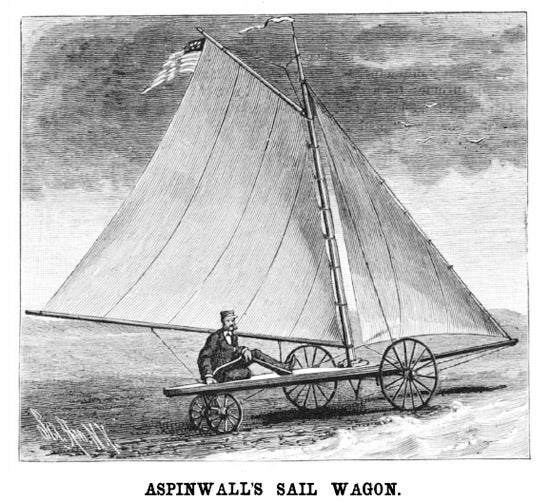

The Sail Wagon was built on a triangular frame, narrow in the rear and wide in the front. A long axle with large wheels was attached to the front, and a shorter axle with smaller wheels, which were pivoted by a kingbolt, was attached in the back.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

"To the short axle is attached a gear wheel into which meshes a smaller wheel secured to the lower end of a vertical shaft journaled in bearings fastened to the frame. Upon the upper end of this shaft is the hand wheel or tiller, by means of which the wagon may be guided. The speed of the wagon is regulated by breaks upon the front wheels, connected with an upright lever pivoted in the middle part of the frame and provided at its upper end with a crosshead so that it can be operated either with the hands or the feet."

A mast and sails were attached to the middle forward part of the frame and could be controlled in the same manner as a regular sailboat. This construction allowed the Sail Wagon to travel "with, on, or against the wind" at great speeds on hard land or beach, allowing for all the glory of billowed sails without the worry of getting wet.