This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

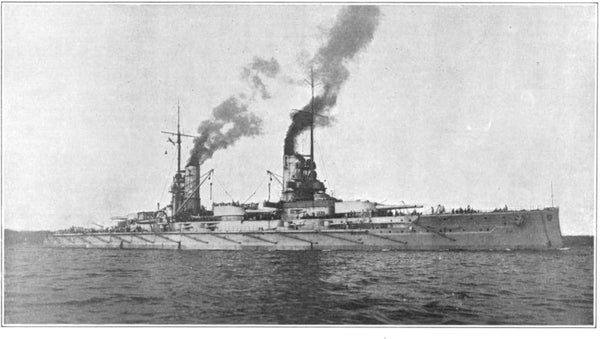

“Der Tag.” Readers familiar with the First World War may come across a mention from time to time of the after-dinner toast that may—or may not—have become popular before the war by officers and men in the German Navy. “Der Tag” translates as “The Day” and reports of it usually interpret it as the after-dinner toast given to the day when the Imperial German Navy would test itself in battle against the British Royal Navy.

The Anglo-German naval arms race from 1898 on is often cited as one of the causes the led the world into war in 1914. There was definitely an undercurrent of competition if not hostility between the two navies. There are references to this toast sprinkled in the literature, some of which may be purely the result of propaganda. I came across a mention of the toast recently in Scott Anderson’s fine history of Lawrence in Arabia (Doubleday, 2013) as encountered by one of the protagonists, William Yale, in 1913. The toast by German officers is also mentioned in Sir James Rennell Rodd’s Social and Diplomatic Memories, 1884–1919, as being “well known” among Swedish Naval Officers prior to 1908. It is carried in newspaper reports from 1915, but by then, perhaps the effects of propaganda had taken the rare instances of this toast and magnified their import and frequency.

Certainly, after the end of the war, the name “Der Tag” was given, by the Allies, with some vengeful bitterness, to the day when the German fleet was surrendered to the Allies on November 21, 1918.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In an article in Scientific American from this day 100 years ago, an article by a Capt. Z. S. Hollweg, of the “German Naval Department” mentions this toast, denies that it ever happened, and (in passing) blames the rapacious English love of mercantilism for the war. Here’s the quote, from the article that looks at the Battle of the Skagerrak (Battle of Jutland, as the British called it):

What the Navy Thinks

Long before the present murderous war broke out, and in spite of all effort at refutation from authoritative German sources, Englishmen have spread the fairy tale that at every banquet German naval officers drank ‘to the day’; that is, to the day on which the German power should be called upon to measure itself in conflict with English skill. It is not necessary to point out here that this whole invention had an inciting tendency of the worst sort. The German naval officer has always had the highest regard for the English comrades with whom, in foreign countries, he has often and gladly associated upon most friendly terms.

We all know that we have learned much from the English navy, we know the glorious histories and traditions of English sea-power. We know that on the true ‘Glorious 1st of June’ [June 1, 1794 between the British and the French navies] namesakes of the ‘Invincible,’ ‘Defence,’ and ‘Marlborough,’ which now on this June 1st [1916] our guns have laid low, fought in the victorious English line. We knew English history so very well that we were perhaps a bit inclined to over-value its lesson. With the history of the origin of the present-day British sea-power, built up upon the ruins of every commercial competitor—first Spain, then Holland and France—we were familiar. The envy and hate with which our maritime syndicates were met in England spurred us on to complete at the earliest possible moment the undertakings which were necessary to justify our confidence and put the defense of Kaiser and country in our hands, if it should come to pass that the appeal to arms must be made. We prepared ourselves in advance to do our duty should the Fatherland call. No more, no less.

Bloodthirsty hatred or envy of England's fleet we have never cherished. That, in case of necessity, the navy would be eager to do its duty, every single man has solemnly and silently vowed. Drinking and toasting in this connection would have seemed to us the height of bad taste. When the war at length broke out, we were eager to show the worth of our fathers and to return our thanks for all the love and inspiration with which the German people in the past few decades had advanced the growth of its darling child, the fleet.”

My take, as a blogger, for what it’s worth, is that the captain “doth protest too much, methinks.” There is a “Captain Hollweg” mentioned in 1917 in the American Journal of the Military Service Institution as being “the former head of Von Tirpitz’s press bureau” so Capt. Hollweg’s statements as a military public relations mouthpiece would be quite in line with the German propaganda that they had no militaristic intentions and that the war was forced on them.

-

Our full archive of the war, called Scientific American Chronicles: World War I, has many articles from 1914–1918 on politics and propaganda in the First World War. It is available for purchase at www.scientificamerican.com/products/world-war-i/