This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Whereas there may be many interpretations of what a smut machine is or does, the one I’ll be talking about is the invention featured in the April 2, 1859, issue of Scientific American. The smut referred to here is the parasitic fungi found on wheat grain.

It is imperative to remove the smut from the grain in order to produce usable flour—a product valued as a food source and for the sensory experience it provides:

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“There is nothing in the range of common substance which is so full of pleasure as flour. It is agreeable to the touch and taste and sight, and whenever one sees a barrel of fine flour opened, the impulse is to bury one’s hands in it and move the fingers among its fine smooth particles.”

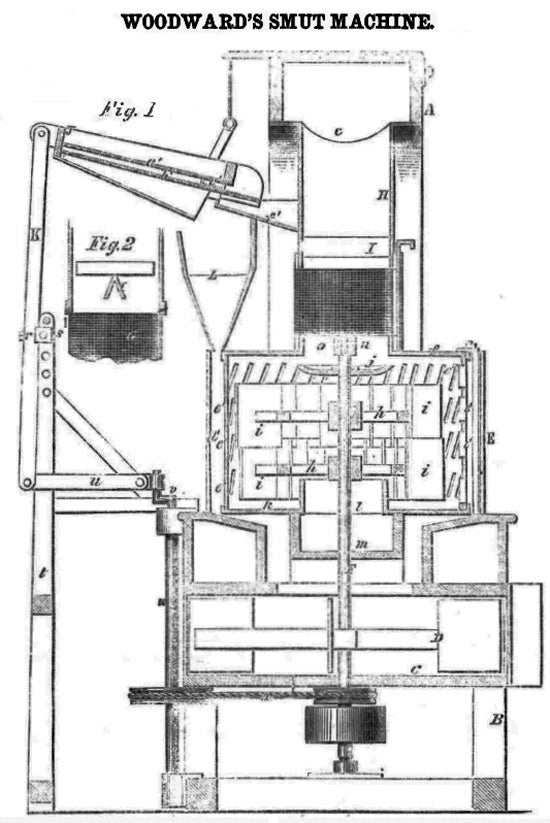

J.A. Woodward of Burlington, Iowa created his Smut Machine to clean the smut and dirt from wheat and separate the wheat from its shell—tasks that would otherwise have to be done by hand. Basically, once grain was poured into the machine, it would pass through screens and spouts, eventually being scoured and “blasted” with air from a fan-box to remove dirt and smut. It would then pass through a series of “beaters” and on to more blasts of air to ensure its cleanliness.

For those who are interested, here is a more detailed explanation of how the machine worked:

“The grain to be cleaned falls on a screen, a’, in the shoe, J, and passes through this screen, the large foreign substances passing off through the spout, c’. The grain cannot pass through the screen, b’, but is conducted by it and the spout, f’, into the cylinder, H. and it falls into the scourer, R, being divided in its descent by the bar, I. The cockle and fine seeds pass off the inclined bottom of the shoe into the hopper, L, and thence through an opening, into the fan-box, C. The fan, D, causes a blast to pass vertically upward through the spout, m, and scourer, E, and the same fan also causes a blast to pass through the spout, A, a current also passing through the wire cloth cylinder, H, into the part, c, of the blast spout, A...The grain, as it enters the scourer E, (through the opening, n, the flange, o, of the top-plate, f, supporting G,) will be deprived of all loose dirt and smut...The grain is spread by the concave, j, and operated upon by the wings or beaters, i, in a very effectual manner, the postition of the beaters operating in a very direct matter against the grain, so as to subject it to the greatest amount of attrition without breaking it.”

The article doesn’t specify whether or not the germ and bran were lost during the scouring process. If they were, then the grains would be considered “refined” as opposed to “whole” and would have lost a good portion of their nutrients along with their smut. I would also add that if the sight of flour moves you to want to run your fingers through it, wash your hands first…otherwise all that scouring and blasting may go to waste.