This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Editor’s note (4/2/2017): This week marks the 100-year anniversary of the U.S. entry into the First World War. Scientific American, founded in 1845, spent the war years covering the monumental innovations that changed the course of history, from the first tanks and aerial combat to the first widespread attacks with chemical weapons. To mark the centennial, we are republishing the article below and many others. For full access to our archival coverage of the Great War sign up for an All Access subscription today.

Reported in Scientific American, this Week in World War I: September 11, 1915

“Never, in the annals of the world, has there been such a powerful awakening of altruistic feeling,” By the time these words were published in our September 11, 1915, issue, two million people had been killed in the fighting in the Great War, four million wounded, and tens of thousands had lost limbs. The hopeful tone of the article therefore seems oddly discordant with the reality of the time.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The author was a Dr. Alfred Gradenwitz, who lived in Berlin and was a regular contributor to Scientific American and other European and American periodicals. The optimism displayed by Gradenwitz perhaps reflects that fact that the standard of care given to soldiers who could not recover from their injuries was not as abysmal in 1915 as it had previously been. Germany, in comparison with other countries, began early on to provide relatively comprehensive government care for those soldiers who were permanently impaired and could not return to fighting. Other countries were slower to respond and cobbled together a rougher patchwork of private charity and public medical care. At least in Germany the main objective of the care provided was to ensure that the individual could resume working and earn a living.

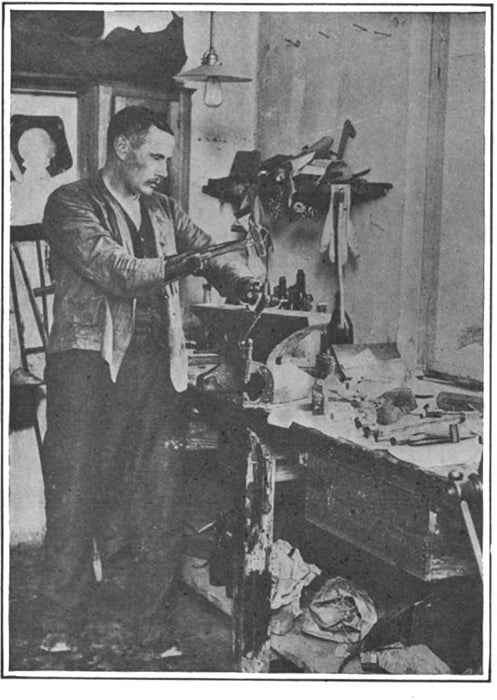

The original caption says, “A man fitted with four artificial limbs, working at the anvil and drill.” Credit: Scientific American, September 11, 1915

The terminology and tone is a little grating to us now, and our priorities for medical and psychological care are different—and hopefully more advanced—but we have had a century to learn from those who have answered the call to fight for their country’s defense:

“How War Cripples Are Taught to Do Without Hands and Feet”

“What was formerly the lot of soldiers who, on the battlefield, had lost their sound limbs and fitness for work? Unable to earn their living by some useful pursuit, short of organ grinding, they were mostly doomed to live on private charity or scanty pensions allowed by the State. Their life's activities were come to a premature stop, and the gloom of an idle, useless existence was all there was in store for them.

“Already, after one year's duration, the gigantic confiict being waged in Europe has crippled unprecedented numbers of men, belonging to the most valuable and. productive class of citizens. Are these hapless beings to spend the rest of their lives in sterile inactivity, a burden to others and themselves? Our keen social conscience shudders at the very thought of this possibility, and modern science comes to the rescue.

“There are those whom no doctor's skill can restore to their previous condition, those who also have lost some limb or other. Even these have no reason to despair, modern orthopedy teaching the art of making artificial limbs of remarkable mobility and efficacy. After undergoing a course of instruction at one of the special cripples' homes, sucn as the Oscar-Helene-Heim, at Zehlendorf, near Berlin, or the Hindenburg House, at Koenigsberg, those wearing such attachments will be able to take up practically any manual profession. The first task of the instructor, in these homes, consists of making the patient independent of his friends and reawakening in him the self-confidence which he has lost.

“Already at the hospital, during convalescence proper, he has been induced to idle away his time with manual work of the most varied description, thus preventing him from brooding over the outlook on his future life. At the cripples' home, where he finds the military orders so familiar to him, he learns, from early morning till late at night, how to do without the help of others, and how to perform such operations as belong to our daily life. Dressing, washing, making his bed, eating and drinking, cutting his meat and bread with one hand only, all this affords an opportunity of useful exercise and is soon mastered by the patient. Left-hand writing is readily acquired by those whose right hand has been paralyzed or amputated.

“The most important part of this instruction, however, begins in the workshops connected with the home, where locksmiths, joiners, shoe-makers, tailors, basket-makers, book-binders, etc., are afforded an opportunity of attending to their trades, under the unwonted conditions created by the wearing of artificial limbs. Those who, all day long, work here at the anvil or carpenter's bench, soon lose any sense of being invalids and are filled with fresh hope for the future.”

-

Some further reading on this difficult subject:

2014: War and Impairment: The Social Consequences of Disablement. UK Disability History Month, November 2014.

http://ukdhm.org/v2/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/UK-Disability-history-month-2014-Broadsheet.pdf

Disability and Masculinity in the First World War. Dr Jessica Meyer. Posted at The History Press Blog, June 14, 2014.

http://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/index.php/updates/disability-and-masculinity-in-the-First-World-War/

The Living Death: The Repatriation Experience of New Zealand’s Disabled Great War Servicemen. Elizabeth Anne Walker. Master’s thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, February 2013.

http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10063/2641/thesis.pdf?sequence=2

Our full archive of the war, called Scientific American Chronicles: World War I, has many articles from 1914 to 1918 on the development of medical care and rehabilitation during the war. It is available for purchase at https://www.scientificamerican.com/products/world-war-i