This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

The headline for the article in the issue from 100 years ago today is short, sweet and enthusiastic—bordering on gushing: “Our Superb Battle-Cruisers.”

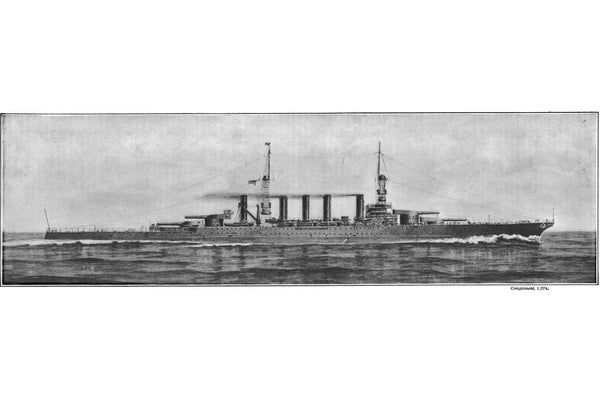

“By the courtesy of the Secretary of the Navy, we are enabled to publish the above official drawing of the accepted design for our new battle-cruisers, the construction of a division of six of which was authorized last summer. It will be agreed that, without exaggeration, these stupendous war ships, in their combination of size, speed and power, must be considered to be the most novel and sensational (if we may use the word) ships designed for any Navy since the day of the British “Dreadnought.” They have the length of the largest transatlantic liners, the speed of the fastest destroyers, and the gun power of a modern battleship. On one point only, that of armor protection, is information lacking. The SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN does not know exactly the thickness and distribution of this armor, and if we did we would not tell; for if there is one feature of warship design more than any other upon which the Naval Constructor is silent, it is that of the armor plan of new ships.”

The idea was a hard-hitting ship with the predatory speed and big guns to catch and destroy the fastest cruisers sent to sea by the enemy (whichever country that might turn out to be). The battle-cruiser was supposed to be able to hit hard and still be able to outrun lumbering dreadnought battleships. The concept for the design had first been floated in 1909 and was quite popular in naval thinking. The British and Germans had built several such ships; even the Japanese navy (then an ally to the U.S. and Britain) had been equipped with one from Vickers in the U.K. in 1913, the Kongo.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

As historians, we have the privilege of knowing how the story ends. In the case of battle-cruisers, not well.

Battle-cruiser deck plan, 1916. It doesn’t show the flaws in the concept. Credit: Scientific American, December 16, 1916

You’ll notice in the text from 1916 that there is an aversion to talking about armor. The thinking back then was that speed would make armor less important: armor was heavy, the less of it a ship had, the more speed it could achieve. Compare the Royal Navy’s HMS Queen Elizabeth, arguably one of the most powerful ships on the ocean after launching in 1913, with a maximum speed of 24 knots. HMS Queen Mary, commissioned just a year earlier, had less powerful guns, but a maximum speed of 28 knots. The main difference was in the belt of armor protecting the vitals of the ship: 13 inches for the “Lizzie,” and between four and nine inches for the Queen Mary.

It wasn’t enough armor.

At the Battle of Jutland on May 31 to June 1 , when the British battle-cruisers slugged it out with German battleships that were just as well armed, but better armored, they came off second-best, catastrophically. The Queen Mary and HMS Princess Royal were hit by shellfire and blew up. Vice-Admiral David Beatty, commanding the British battle-cruiser squadron, is said to have turned to his flag captain and remarked “There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today.”

Indeed there was something wrong: a faulty concept. In the ensuing years, ships that had originally been designed as battle-cruisers, such as the Royal Navy ship HMS Hood were hastily fitted or retro-fitted with more armor. The Hood was supposed to have even more armor plate installed but the plans were put on hold when World War 2 broke out. In 1941, after a ten-minute battle with the German ship Bismarck, the Hood was blown up by a 15-inch shell; only three of the ship’s crew survived.

The Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 effectively made the design a moot point. Nations concentrated on building the largest and best-armored battleships allowed under the treaty. The six battle-cruisers planned by the American navy were never finished, but the hulls of two of them were converted into fast fleet carriers USS Lexington and Saratoga.

The views expressed are those of the author and are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

Our full archive of the war, called Scientific American Chronicles: World War I, has many articles from 1914–1918 on technological developments in the First World War. It is available for purchase at www.scientificamerican.com/products/world-war-i/