This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

In an attempt to get around the iron grip of the British naval blockade of Germany, a North German Lloyd subsidiary built two unarmed cargo submarines, capable of sneaking underneath the screen of Royal Navy warships.

In early July of 1916, one of these submarines, the Deutschland, slipped into Baltimore harbor, stuffed with 700 tons of cargo. The weight of goods carried was small in comparison with an average freighter, but the reaction from the British and French was outsize. The Allies, knowing their naval blockade was in jeopardy, protested loudly. The Americans, obliged to cling to a veneer of neutrality, dismissed the protests because the submarines were unarmed, and commerce was still legal. The crew were treated as plucky heroes. The propaganda value for Germany was priceless. The Deutschland made a second visit in November 1916, and as with the first visit, it was a poke in the British eye.

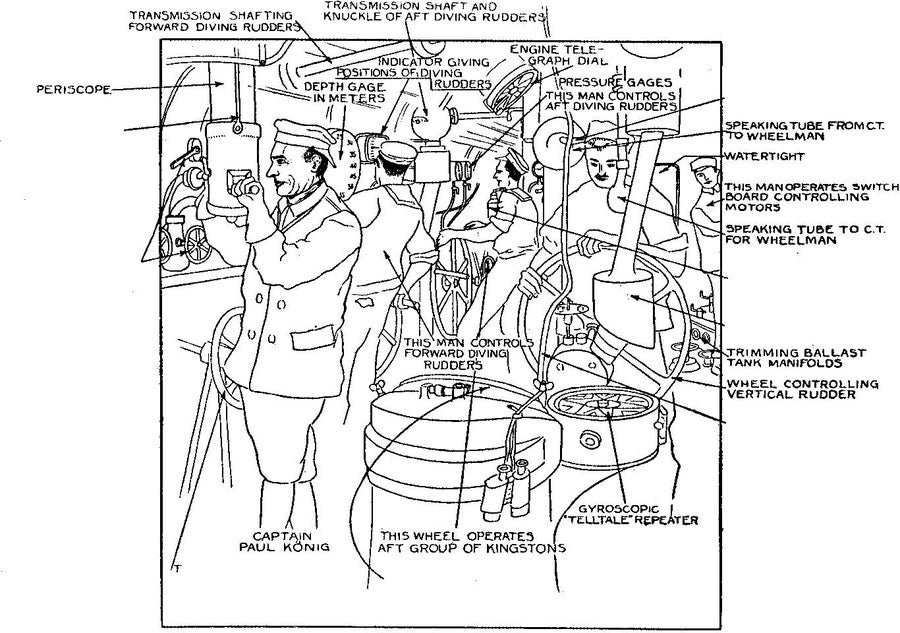

In the earlier visit an American had been invited onboard the vessel to take a tour: the noted marine artist Henry Reuterdahl. Unlike most artists of the day, this one was well acquainted with technical aspects of modern warships: he was also at one point a lieutenant commander in the United States Naval Reserve. He provided a cover illustration and a description of the interior of the submarine that was published in the issue of Scientific American from 100 years ago today:

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“The policy of secrecy which the owners of the merchant-submarine ‘Deutschland’ have followed was broken recently in the case of the marine artist, Mr. Henry Reuterdahl, when he was permitted to make sketches of the interior, which were worked up by the artist in the very interesting drawing which is shown on the cover of the present issue. The following article is based upon notes taken by Mr. Reuterdahl during his several hours’ stay aboard the vessel.”

“The ‘Deutschland’ is 230 feet in length and is built on the usual system of a circular hull proper, with what might be called an enlarged false hull outside of this. The beam of the hull proper is 17 feet, the full beam of the ship, out to out, is about thirty feet. She is driven by Diesel engines, developing 1,200 horse-power, the engines being six-cylinder, two on each shaft. The speed on the surface is 14 knots, and submerged 7 1/2 knots. The time to submerge from surface conditions is two minutes.”

Detailed key to color image of the interior of the World War One cargo submarine “Deutschland.”

Credit: Scientific American, February 10, 1917

“According to Capt. Koenig, the total distance run under the submerged condition on the last trip from Germany was 180 miles. It is estimated by American shipping men and naval architects that her cargo capacity is about 750 tons. According to Capt. Koenig, it is 1,000 tons. The entire crew with the officers consists of 29 men. There are three navigating officers, including the captain, and one chief engineer who attends to the submerging of the vessel. The engineers and mechanicians, who come from Krupps in Kiel, are all civilians. The head man from Krupps remained in the United States, thereby indicating that other German submarines are expected to arrive.”

The sister ship, a cargo submarine named Bremen, was less fortunate, and disappeared at sea on its first voyage to the U.S. in September 1916. But perhaps it mattered little: within two months of this image being published, America had declared war on Germany, ironically over the matter of Germany using its submarines to sink American ships. The German navy had by then appropriated the Deutschland and installed torpedo tubes and deck guns.

The views expressed are those of the author and are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

Our full archive of the war, called Scientific American Chronicles: World War I, has many articles from 1914–1918 on the politics and propaganda of the First World War. It is available for purchase here