This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Reported in Scientific American, this Week in World War I: August 7, 1915

The Great War had been raging for a year. This week’s edition of Scientific American had several articles assessing that unfortunate anniversary. There is an interesting difference between the accuracy of reporting in some articles and the haze of obscurity drawn by the military censors over still-volatile events.

The article by “Capt. Matthew E. Hanna , Recently of the General Staff U.S.A.” is a concise portrait of the outbreak and first year of the war, starting with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, Bosnia. Hanna discusses the diplomatic wrangling that accompanied the descent into war, drawing conclusions that, for all the arguments over the decades, are largely valid today. He details quite accurately the military successes and failures of all sides in the first year of the war. Perhaps he was adept at interpreting maps: where the fighting took place shows where the front lines were, how the armies were doing and what their objectives were. He notes the strategic importance of railways that allowed German troops to rapidly shift long distances. (The masterful modern history by Christopher Clark, The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 (Harper, 2013), describes the pre-war diplomacy and financial wrangling that led to railway construction specifically for critical military use.) Hanna understood clearly the central German strategic goal of attempting to fight France and Russia one after the other, and not at the same time:

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“So outnumbered were the Teutons by the coalition against them, that their only reasonable chance for decisive success lay in their concentrating overwhelming force against the enemy on one front at a time.”

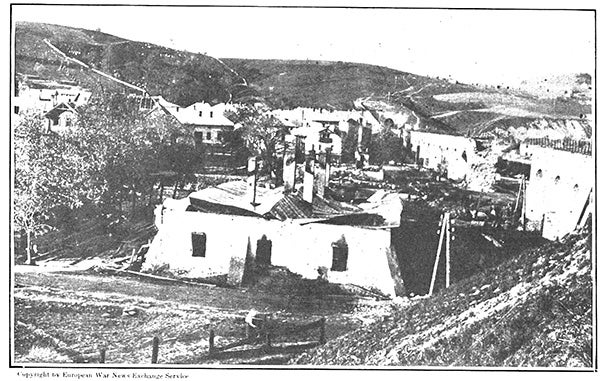

The original caption reads: “East Galicia has been devastated by the Russians as they retreated.”

Image: Scientific American, August 7, 1915

Another article in this week’s issue has a very different approach. J. Bernard Walker, an authority on shipbuilding (who also dabbled in science fiction), discusses naval operations, but basically throws up his hands in despair and writes:

“Until the war is over and authentic official lists of these losses have been made public, any attempt to give such statistics would be guesswork to such an extent as to vitiate the value of the results arrived at. Thus, if the ‘Audacious’ were destroyed as rumored beyond recovery, the loss of that valuable ship alone represented a reduction of fighting strength equal in value to that of all the old battleships sunk in the Dardanelles operations. As a matter of fact, the Admiralty has never acknowledged her loss, and the lay evidence that she was sunk is counterbalanced by other explicit lay testimony, confirmed by much unofficial expert testimony, that she did not sink, but was brought into port, repaired , and is now in commission.” (The Audacious was sunk by a mine at sea, but that fact was a closely held secret until the end of the war.)

The naval war in 1914-1918 could not be followed by looking at ship dispositions or territory held or how front lines were shifting. Losses were capricious—the result of good or bad luck in where and when ships, submarines and mines encountered one another—and information about such reverses was held in tight secrecy by the authorities of all countries.

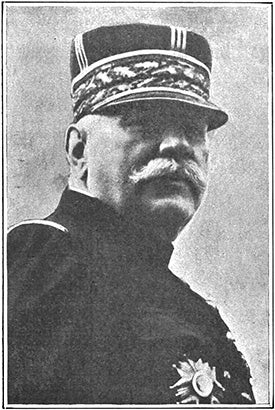

General Joffre, commander-in-chief of the French armies.

Image: Scientific American, August 7, 1915

Where operations were still ongoing (perhaps particularly if the outcome was in doubt) there is also considerable obscurity:

“To open the Dardanelles and to reach Constantinople, the British and French finally landed an expedition on the narrow Gallipoli peninsula. For months this force has been steadily creeping nearer to the forts that are the key to the peninsula and the straits.”

By August it was becoming clear that unless plentiful reinforcements were poured into the effort in Gallipoli, the campaign would stall at best and at worst turn into a disaster for the Allied forces and a huge success for the Turkish Ottoman Empire. By January 1916 the Allied troops had abandoned the campaign and withdrawn.

The other area of the war that was still shrouded in censorship was in the desperate fighting between Italy and Austria in the harsh Alpine terrain between those two countries. The Italian plan had been to break through the mountains and invade the low-lying areas of the Austro-Hungarian Empire near the coast (land that Italy believed it had some claim over):

Field-Marshal von Hindenburg, “the most conspicuous general on the German side.”

Image: Scientific American, August 7, 1915

“For two months [Italy] has deliberately and methodically followed this plan. At the Isonzo River on her eastern frontier she was met by the Austrian army supported on powerful fortifications and for weeks she has been hammering at this line. As this is written rumors reach us that Austria’s main defensive bulwark at Gorizia is about to fail.”

The Austrians held fast until October 1917. At that time they inflicted a crushing defeat on the Italians at the Battle of Caporetto (also known as the 12th battle of the Isonzo River).

One aspect of the war receives no mention at all anywhere in the issue: the horrific casualties that had been suffered. Large industrially advanced nations had sent vast well-armed troops to fight one another with predictable results: At this stage of the war about two million men had been killed and another four million wounded.

-

Our full archive of the war, called Scientific American Chronicles: World War I, has many articles from 1914–1918 on all aspects of the war. It is available for purchase at www.scientificamerican.com/products/world-war-i/