This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Armies dug trenches in the First World War to shelter from the power of the machine gun and the destructiveness of artillery. These deep, well-protected trenches sat behind fields of barbed wire protected by their own artillery and machine guns. One way to attack these trenches was with artillery. But large guns were expensive, and the precision-manufactured ammunition for them took up a large proportion of manufacturing capacity.

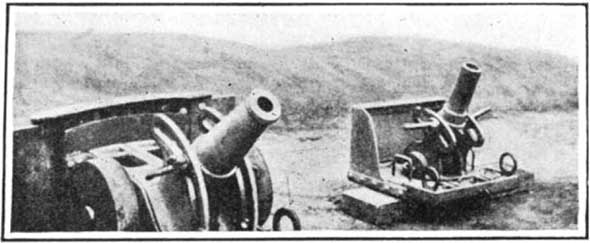

One technological fix for trench warfare updated an old idea: a short-range mortar firing a large explosive bomb. The article in Scientific American Supplement from February 26, 1916, introduces the French-designed 58-millimeter trench mortar [see photographs] and gives credit to General Jean Dumézil, a noted artillery officer, for the work involved in updating it.

The French nicknamed the mortar the “Crapouillot,” meaning “Little Toad,” because of its squat appearance. These weapons were used widely by the French and American armed forces until the end of the war.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The “Little Toad” mortar—squat, ugly, effective in trench warfare.

Image: Scientific American Supplement, February 26, 1916

The bomb thrown by this weapon was much larger than its caliber. A warhead attached to a spigot (basically a rod), which was inserted into the barrel of the mortar. The wings on the bomb enabled it to land nose first. The device could fire several sizes and configurations of bombs, weighing from 18 to 35 kilograms (40 to 77 pounds). With different propellant charges these could be thrown, accurately enough, from 100 to 1,450 meters. And they were cheaper to mass-manufacture than artillery shells.

The 1916 article was written about a weapon that was still classified, so details are sparse. But we have some details from a pamphlet prepared by the American Expeditionary Forces in France, March 1918, titled “ Manual for Trench Artillery, United States Army, Part V: The 58 [millimeter] No. 2 Trench Mortar” (the copy I looked at was declassified in 1949). To destroy targets such as blockhouses, “60 to 80” larger bombs or “100 to 150” smaller bombs were required. To make “a passage 40 meters wide in an entanglement 30 meters deep” needed 60 to 80 larger bombs or 100 to 150 smaller bombs. The bombs could also carry poison gas or could, in theory anyway, be used to “break up” the poison gas clouds of the enemy.

-

Our full archive of the war, called Scientific American Chronicles: World War I, has many articles from 1914–1918 on contemporary coverage of weapons technology of the First World War (although the Scientific American Supplement issues are not yet available in it). It is available for purchase at www.scientificamerican.com/products/world-war-i/