This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Great one-horned rhino Rhinoceros unicornis in enclosure at the brilliant Chester Zoo, UK. Photo by Darren Naish.

I’ve just learnt that today is World Rhino Day. This always happens: I learn about these things on the day and am completely unaware of them beforehand. I apologise if all this shows is that I’m badly organised and not paying enough attention to what’s being covered on the zoological newswires. Anyway...

As per usual, I don’t have anything prepared. So what I thought I’d do instead is use this opportunity to produce a clearing house of rhino-themed Tet Zoo articles. I’ve covered rhinos (living and fossil) on at least a few occasions and have many images of rhinos taken in zoos, museums and so on. I’ve also been drawing rhinos for my grand textbook project (for more on that please go visit the Tet Zoo patreon project). As usual with Tet Zoo, my aim here is to talk about some of the less well known things about rhinos, not the same old things that you’ve heard a hundred times before.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Awesome scenes of rhinos fighting other animals, from the Animal Life and The Private Lives of Animals books, published by Casa Editrice AMZ

War rhinos. A Tet Zoo classic dating to March 2007 – it was inspired by the appearance of an armoured war rhino in the then-new movie 300 – describes my efforts to determine whether rhinos (of any species) were once used as armour-plated war beasts. The short answer is: they almost certainly were not, alas. The longer answer: go and read the article. The article makes mention of Jared Diamond’s reference to the fact that African rhinos never were (so far as we know) domesticated or used by people; this alludes to Guns, Germs, and Steel (Diamond 1997), and many of you will know that Diamond’s premise and argument put forward in that book has been the subject of substantial, err, critique within recent years.

Great one-horned rhino in a heated pool at Edinburgh Zoo. Photo by Darren Naish.

Rhinos can swim. A few sources here and there say that rhinos cannot swim. It’s not true: they can, as can those other mammals (pigs, camels, giraffes) sometimes said to be incapable of this action. In October 2008 I somehow obtained a poor photo of a Great one-horned rhino swimming across a river (I think the photo comes from a book – I’ve lost the source now) and it formed the subject of one of those Tet Zoo guessing games.

Reclining female white rhino photographed at Marwell Wildlife. Image by Darren Naish.

The white rhino is not the ‘wide rhino’. Most books and other sources will tell you that the rather silly name ‘white rhino’ refers not to Ceratotherium’s colour, but to some other aspect of its life appearance, most likely its wide lips. It is, after all, a square-mouthed, grazing, ground-feeding rhino, not a hook-lipped browser like most of its relatives. However, as explained in detail by Rookmaaker (2003), and as then summarised at Tet Zoo in January 2009, this explanation is almost definitely bogus. I’m not about to summarise the whole argument again here, so go check out that 2009 Tet Zoo article if you’re interested.

You might be interested to know that this article was also converted into comic form by the brilliant Ethan Kocak...

Having mentioned rhino specialist Kees Rookmaaker, let me use this opportunity to point you to the excellent Rhino Resource Centre that Kees curates. This is a spectacularly impressive online resource where pdfs and other files are collated. Check it out!

Sumatran rhinos are great, but they aren’t really ‘living fossils’. I like all rhinos a great deal, but I suppose I’m especially fond of the Sumatran rhino Dicerorhinus sumatrensis, a shaggy-furred, ‘small’ rhino that’s critically endangered and restricted to tiny, peripheral segments of what was once a broad geographical range. Sumatran rhinos are tough, adaptable and ecologically flexible – there are great anecdotes where they’ve been seen climbing high on steep mountains, traversing dangerous riverbanks, and even frequenting beaches and swimming in the sea. Back in April 2009 I wrote a short article about this species, and one thing I focused on was the annoying claim that it’s a ‘living fossil’ – a vestige of a past age, clinging precariously to existence and surrounded by younger, more beautiful animals that have sprung to life’s stage in the time that it has languished in the shadows, dragging its evolutionary feet.

Excellent shot of Sumatran rhino pair, photo by Charles W. Hardin, CC BY 2.0.

The problem with claims of this sort is that they tend to be attached to animals that ‘feel’ or ‘look’ anachronistic when they aren’t, in fact, any more anachronistic than a great many other animals never regarded as such. Yes, there are close fossil relatives of the Sumatran rhino from the Pleistocene and Pliocene (that is, species that are at least a few million years old). But there are a huge number of other living species with close relatives equally as old, if not older, and yet nobody ever considers them ‘living fossils’. Random example: there are peafowl, turkeys and chickens several million years old, yet when was the last time you saw someone point to a turkey and describe it as a living anachronism? The situation is made all the more ironic when you consider that (1) Sumatran rhinos don’t have a fossil record, and (2) the features that make the Sumatran rhino seem ‘archaic’ may be recently evolved novelties, not primitive features inherited from ancient ancestors (Cerdaño 1995).

And there’s more on this subject (the subject of whether Sumatran rhinos are ‘living fossils’ or not) at the 2006 Tet Zoo ver 1 article Are Sumatran rhinos really ‘living fossils’?

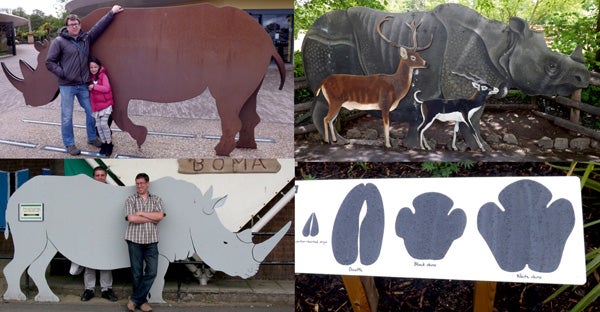

Rhino-themed installations encountered at zoos. Clockwise from top left: sheet-metal Black rhino Diceros bicornis at Chester Zoo, Great one-horned rhino (with Eld's deer and Blackbuck) cutout at Chester Zoo, life-sized footprint silhouettes at Marwell Wildlife, life-sized wooden White rhino at Marwell Wildlife.

Are there two living white rhino species?Back in May 2010 I covered Colin Groves et al.’s proposal that the White rhino Ceratotherium simum does not consist of two ‘subspecies’. Rather, Groves et al. (2010) argued, the two taxa – the Southern C. s. simum and Northern white rhino C. s. cottoni – are distinct enough, morphologically and genetically, to be raised to species level (C. simum and C. cottoni, respectively). They seem to have been separate for a million years or so which is, from the ‘mammal’s eye view’, easily long enough to rack up ‘species level’ differentiation. As with all suggestions of this sort, the proposal is subjective – sure, everyone agrees that those two phylogenetic entities are distinct, but how we reflect this distinction when it comes to the taxonomic conventions we follow is down to preference, not to anything quantifiable. What’s happened to this idea since Groves et al. (2010) published it? My impression is that it hasn’t really caught on. We still see the two white rhinos being referred to as subspecies on virtually every occasion.

Complete fossil skeleton (though this is a replica, at OUMNH, Oxford) of baby rhino Subhyracodon. Photo by Darren Naish.

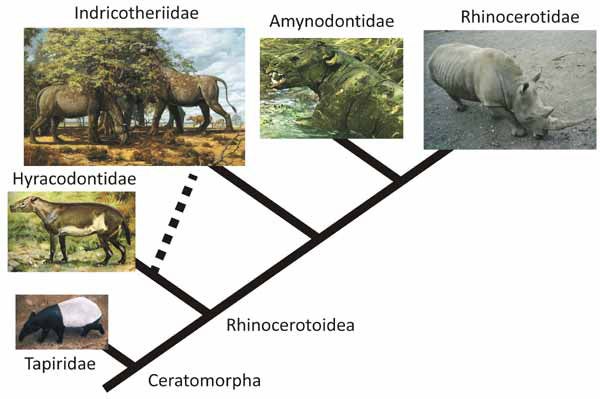

There are an absolute crapload of obscure fossil rhinos. Rhinos are one of those groups that I just don’t feel I’ve ever given due time to here at Tet Zoo. I’ve mentioned one or two fossil groups, but have never provided any sort of useful review. The good news is that I now have an excuse to produce just such a review since I’m putting one together for my in-prep textbook (remember: support it at patreon, hint hint). In 2013 I wrote briefly about diceratheriines, an extinct, archaic rhino group that inhabited North America between the Eocene and the Miocene. The article was inspired by the outstanding fossil skeleton of a young baby Subhyracodon, preserved curled up and on its own (not with, or inside, its mother). The article gave me a brief excuse to talk about rhino phylogeny and about the sad plight of living rhinos.

Massively simplified cladogram showing approximate relationships among rhino groups. Artwork by Ely Kish (Paraceratherium, representing Indricotheriidae) and Zdenek Burian (Hyracodontidae and Amynodontidae).

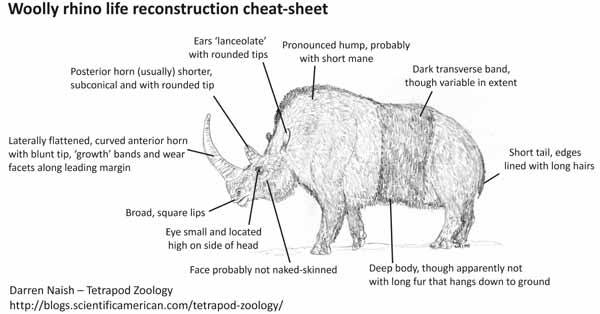

We know a lot about the life appearance of the Woolly rhino. One of my favourite subjects concerns the life appearance of extinct animals (or extinct populations of animals) as determined by ancient cave art. Thank to the artistic or ritual endeavours of our ancestors, enormous quantities of data are recorded on extinct horses, lions, deer, bison, and also on the Woolly rhino Coelodonta antiquus, a shaggy-coated Eurasian rhino that had a distinctive horn anatomy. Cave art shows that woolly rhinos of at least some populations had a very striking coat pattern, and we also know a lot about their soft tissue anatomy. All of this and more was reviewed for a Tet Zoo article published in November 2013.

And that’s more or less it. I plan to do a lot more, but then I always do. Things to cover here in time: the spectacular one-horned rhino, the elasmotheres, and my now overdue review of Don Prothero’s Rhino Giants.

Refs - -

Cerdeño, E. 1995. Cladistic analysis of the family Rhinocerotidae (Perissodactyla). American Museum Novitates 3143, 1-25.

Diamond, J. 1997. Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. W. W. Norton & Co., New York.

Rookmaaker, L. C. 2003. Why the name of the white rhinoceros is not appropriate. Pachyderm 34, 88-93.