This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

As someone who works at the intersection of art and science, I have always found it easy to make the case that all artists are scientists. From the moment we pick up a crayon and make our first mark, we are experimenting. The perceived successes and failures of our craft are indelibly tied to the many variables—physical, chemical and psychological—inherent in the experiences of creating and consuming works of art.

Yet, it seems a longer stretch, somehow, to argue that all scientists are artists. At the very least, in my experience, scientists seem less willing to claim this alternate title. In fact, almost anyone who does not see her or himself as artistically inclined tends to be a little too quick to proclaim, “Oh, I’m not an artist. I can’t even draw a straight line!” With a sigh, I’ll avoid the temptation to digress into the utter irrelevance of straight lines and one’s ability to draw them. Instead, I’d like to posit the idea that, while we may not all identify as artists, scientists, of all people, really should be artists.

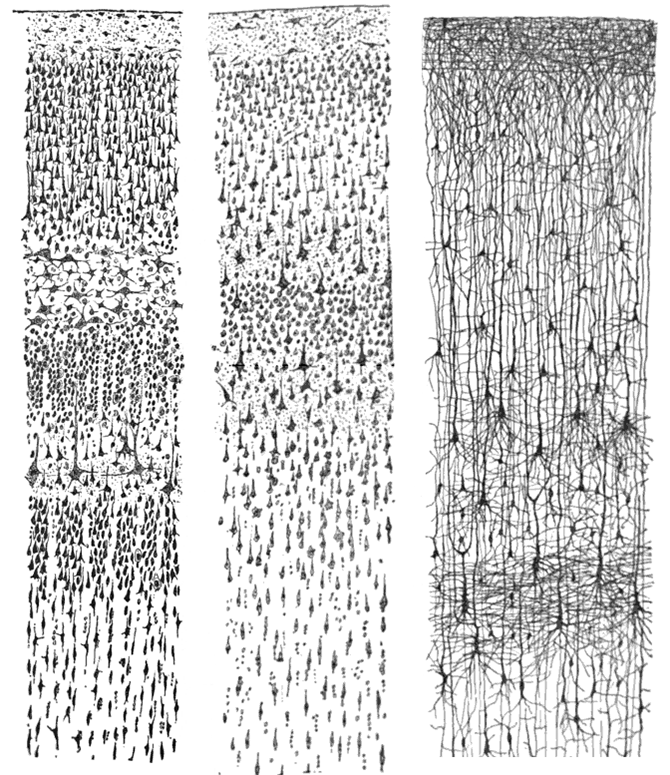

Throughout history, much of scientific discovery and advancement has hinged not just on our ability to see certain things, but also on our capacity to reproduce what we see in faithful, critical and/or meaningful ways. The drawings of the famous Spanish neuroscientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal provide an ideal example of this phenomenon.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In the late 1800s, using a novel histological staining technique developed by Italian physician Camillo Golgi, Ramón y Cajal spent countless hours examining brain tissues under the microscope and recording what he saw in pen and ink. As he observed and drew, he eventually deduced that neurons were not just elements of a mesh-like network, but rather discrete cells, and that each conducted impulses in a single direction—from dendrite to axon. This discovery, known as the neuron doctrine, had a profound impact on neuroscience. Paradoxically, Golgi staunchly opposed the neuron doctrine. Nonetheless, in 1906, the two scientists jointly accepted the Nobel Prize for their respective contributions to medical science.

Drawings by Ramón y Cajal of the human sensory cortex (From Wikimedia Commons)

As biomedical imaging techniques continue to advance, those of us who specialize in the visualization of scientific information are often compelled to question the significance of our role. After all, if we can acquire fantastically thin slices of brain tissue, scan them with an electron beam, import the visual data into a computer, and use it to reconstruct a perfectly accurate three-dimensional digital model of brain cells and their connections, then why on earth would we bother with such a tedious and antiquated pursuit as drawing?

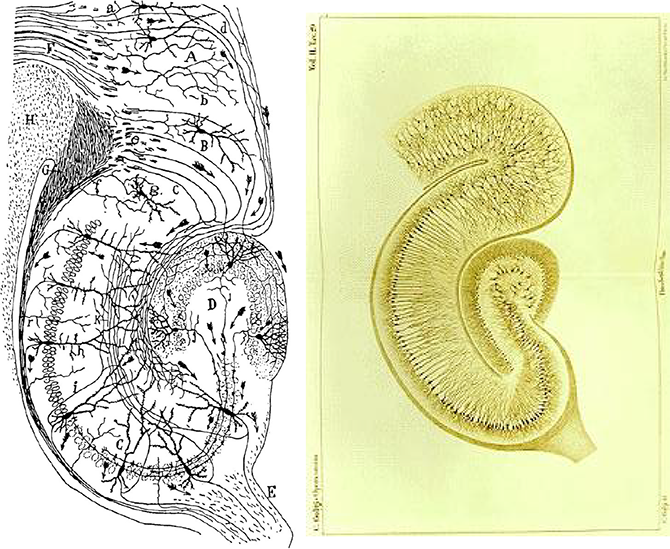

In Ramón y Cajal’s day, the case for drawing was easy to make. It wasn’t possible to photograph what could only be seen through a microscope; scientists had to be artists! But if, after the emergence of Golgi’s staining technique, Ramón y Cajal had proceeded to photograph his histological samples instead of drawing them, would his study have yielded the same epic results? I believe the answer lies in Golgi’s confounding resistance to the neuron doctrine. Golgi’s staining technique was essential to Ramón y Cajal’s discovery because it allowed him to see individual neurons in their entirety. Golgi understood the significance of his own contribution, and indeed, upon studying his own samples under the microscope, his eyes must have perceived something very similar to what Ramón y Cajal saw. Yet he interpreted it very differently, and this alternate reading of the same visual information was manifested in his drawings.

Drawings of the hippocampus by Ramón y Cajal (left) and Camillo Golgi (right)

(From Wikimedia Commons)

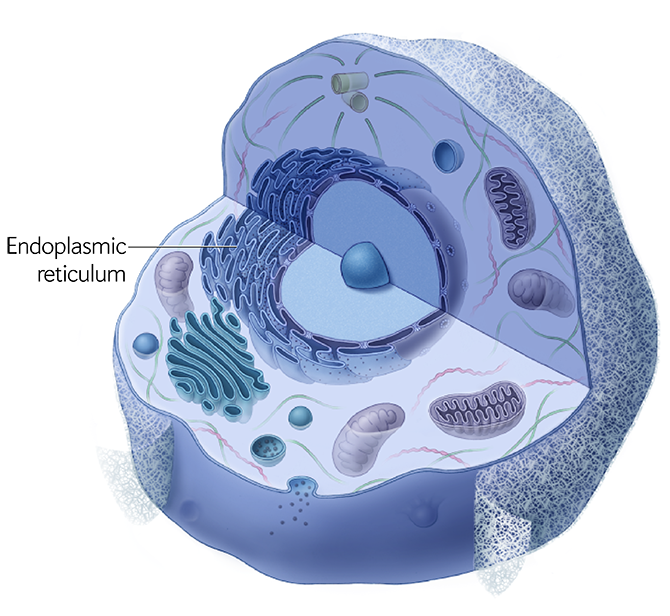

No matter how clearly we can see an object, there is something about the physical act of reproducing and interpreting it visually: in making marks, we infuse meaning into each element of the structure before us. Recently, I was asked to draw an animal cell in cross-section as part of an illustration series I was working on. It’s the sort of image any biologist has seen a thousand times in various renditions: a roughly spherical blob with a 90-degree wedge cut out reveals a sampling of organelles floating in cytoplasm.

While I count myself among those to whom this image is almost tediously familiar, I was shocked at how much difficulty I had in trying to draw the large organelle known as the endoplasmic reticulum (or the “ER,” to those in the know). Admittedly, it’s a complex structure composed of membranes folded into repeated convolutions. But still, I’m a fairly seasoned draftsperson with, I thought, a reasonably solid grasp of cell biology. Yet as I struggled through my pencil sketch, I realized that I had never really understood the physical structure of the ER. I could look at existing images as much as I wanted, but it was only the act of drawing the ER that forced me to fully appreciate how it was put together and how it fit into the context of the cell.

Illustration of animal cell by Amanda Montañez

Perhaps these seem like unfair examples for the case I’m trying to make. I am a professionally trained illustrator, and Ramón y Cajal happened to be an extremely talented and avid draftsman. (As a child, he actually wanted to be an artist, but his father pushed him to pursue medical science instead.) But I would argue that one’s skill level has little effect on the benefit one stands to gain from drawing in science.

Of course, when it comes to communicating science visually to an audience, some artistic skill is usually required. In that sense, Ramón y Cajal’s artistic prowess was fortuitous; it’s why we still use his drawings today, and why we marvel at their beauty as well as the richness of their content. However, I don’t believe that Ramón y Cajal’s big discovery was dependent upon the beauty or even the precision of his neuron drawings; rather, it was the fact that he did draw them, and the process of his drawing, from which the neuron doctrine was born.

Some of the best science classes I’ve had were those in which the instructor did not just incorporate visual content in their lessons, but actually drew during the lecture and encouraged—or, in some cases, required—students to follow suit. Of these instructors, I can only think of one who drew particularly well; the rest were amateurs at best. But this did not diminish in the least the value of their teaching methods. The act of drawing as an element of the learning process served not only to focus my attention on key facets of the information I was absorbing, but also to solidify important concepts in my mind and help me to retain them long after each course ended. Recently, as an anatomy student charged with learning the entirety of gross human anatomy, I spent a lot of time dissecting cadavers and studying illustrations, but I was never sure I understood each anatomical region or structure until I could draw it.

Personally, I think just about everyone (myself included) could stand to draw more, regardless of her or his skill level. Not only is it fun, it’s a refreshingly immersive and stimulating way to observe the world around us. But moreover, for scientists studying structures and processes in an effort to unlock their mysteries and understand them more fully, a pencil and paper just may be two of the most important tools for success.