This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Periodically, I receive letters from prisoners. One recently arrived from an obviously bright person who spotted a math error in one of my textbooks and who offered his life story, quoted here with permission:

I helped a so-called friend commit armed robbery and murder back in 1994. I was just 17 years old when this transpired. I was arrested a few weeks after. Been incarcerated ever since. Been in prison for over 20 years now. Actually been in prison longer than I was ever free . . . I am among the 300 plus “Juvenile Lifers” that exist in Michigan prisons. I learned and matured a lot since my time incarcerated. Yes, I experienced great remorse and regret over the tragedy that I ashamedly participated in. But I salvage this experience by learning and growing from it. I want my life to mean something to someone. To contribute something, anything of substance and worth.

Here in Michigan, our roads are crumbling while our prisons are overstuffed. That makes me wonder: Mindful both of the horrific nature of this teenager’s crime, but also of the immaturity of 17-year-old frontal lobes (which lag the development of the emotional limbic system), does it really make sense—is it in the public interest—to incarcerate this person for life?

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Teens, we know, exhibit impulsiveness. With brains not yet fully equipped to contemplate long-term consequences, they are at risk for succumbing to the tobacco corporations, fast driving, unprotected sex and emotional outbursts.

That fact of life led the American Psychological Association in 2004 to join other health associations in filing a Supreme Court brief arguing against the death penalty for 16- and 17-year-olds. Teens are “less guilty by reason of adolescence,” argued psychologist Laurence Steinberg and law professor Elizabeth Scott. The Court agreed, and in 2012 the APA offered similar arguments against sentencing juveniles, such as my letter-writer, to life.

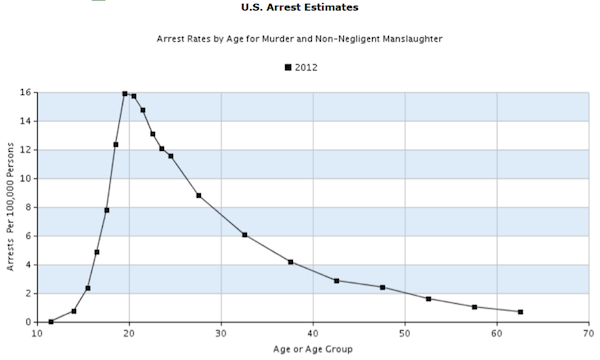

A recent New York Times article summarized data that, additionally, reveal the short lifespan of most criminal violence. For murder, rape, robbery and assault, arrest rates peak around the age at which my letter-writer committed his crime, and then begin their long plummet, as shown by this figure created online for me by the Bureau of Justice Statistics:

As David Lykken noted in his 1995 book, The Antisocial Personalities, “We could avoid two-thirds of all crime simply by putting all able-bodied young men in cryogenic sleep from the age of 12 through 28.” The frontal lobes mature. Testosterone declines. Guys mellow.

A 21-year sentence cap such as Norway has (even for mass murderer Anders Behring Breivik, with possible extensions if he is deemed still a risk) would release violent prisoners only after their criminal career has almost surely ended. A 40- or 50- or 60-year-old parolee is unlikely to rape, assault or murder someone. (Exceptions could be made for convicts who continue to exhibit aggressive behavior in prison, which indicates that they are still at risk.)

The possibility of a mandatory life sentence is not an effective crime deterrent. When committing a crime of passion, people seldom pause to calculate the consequences (which explains why even capital punishment does not predict lower state homicide rates). Any deterrence effect comes more from swift and sure arrest. What matters is not the length of a punishment but its probability.

If violent criminal tendencies seldom extend to midlife, and if mandatory life sentences offer little added deterrent effect but considerable financial and social cost, then is it time to rethink life-without-parole sentencing? Will today’s prolonged mass incarceration seem to our grandchildren as merciless and foolish as yesteryear’s debtors’ prison?

Social psychologist Brett Pelham has an answer. In his new book manuscript, Pants on Fire: Evolutionary Psychology, he notes that “Today, the U.S. makes up less than 5% of the earth’s population but about 25% of the earth’s prison population. Arguably, the biggest part of this huge problem is not that we put way too many people in prison. It’s that we keep them there for a very, very long time.”

But there is good news: a bipartisan consensus is emerging that the costs of prolonged, mass incarceration to U.S. families and public finances is excessive (see here and here). By giving judges more discretion in sentencing nonviolent drug offenders, the proposed Smarter Sentencing Act of 2015 aims “to focus limited Federal resources on the most serious offenders” and to reduce the prison population.