This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

For a few minutes on the afternoon of Friday April 8th 2016 millions of eyes were focused on Cape Canaveral in Florida, and shortly afterwards on a remote 'drone' barge a couple of hundred miles downrange in a choppy Atlantic Ocean.

The cause of all this attention was SpaceX's launch of a heavy payload to space, with a later rendezvous with the International Space Station, and a critical attempt to return the 1st stage booster rocket safely to Earth.

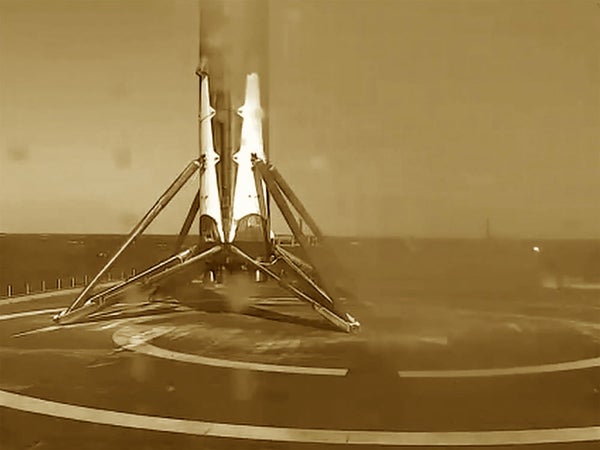

As reported by pretty much every media outlet across the planet, the Falcon 9 made a gloriously easy-looking powered return and landing on SpaceX's drone ship.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

So what's the big deal?

First, getting the biggest and costliest piece of launch hardware back in one piece offers the possibility of reusing it and lowering the expense of reaching space. Back in December 2015, SpaceX had already got a Falcon 9 booster to return to within shouting distance of where it had launched from some ten minutes earlier - on a neighboring pad at Cape Canaveral.

Although it remains to be seen how well these rockets hold up to refurbishment and relaunch, the basic idea is sound. Reuse means drastically lower launch costs in the long run. It might cost $60 million to build one of SpaceX's boosters, but only a few hundred thousand dollars to refuel it. Even if making it flight-worthy again costs several million dollars of engineering tinkering and fixing, that's still an enormous saving.

Except, at least half of the expected launch trajectories from the Cape involve heading over the Atlantic for a distance that makes it infeasible to get back to land in Florida. The boosters simply can't carry enough fuel to turn around and come back.

Hence the ocean-going drone ships (with names like 'Of Course I Still Love You', and 'Just Read the Instructions', lifted from Iain M. Banks novels). These mobile landing sites can chug out to open water to be in exactly the right spot for the rocket to fall back towards from the arc of its launch trajectory, even if hundreds of miles offshore in the Atlantic.

With a successful landing out in the ocean, SpaceX is on its way to covering all the options, so that all launches can involve a gentle booster recovery and huge cost-savings.

And that's where the vision thing comes in.

As Elon Musk and many others have long stated, dropping the cost per-unit-mass of launching to space is critical if our species is going to explore and utilize the solar system. It's also the key to ensuring our long-term survival.

Even if we became model stewards of the Earth overnight - trimming our growth and reversing climate change, undoing pollution and species extinction - we still live on a planet drifting through the cosmos. That's a seriously challenging place to exist without a good backup plan.

The best security deposit we can make is to learn how to live off-world. There are likely many ways to do this, and we don't really know which are best yet. Should we have colony-sized structures in space? Should we go to the Moon? Or should we try Mars?

Mars has a long allure, and SpaceX is in many ways built from the ground up to create the bridge to our 4th planet. But apart from simply getting off the Earth and hauling infrastructure and people to this red world, you also have to deposit all of that safely on the surface. Mars is tricky in this respect. It may be a less massive world, with a gentler gravity field, but it also has a pitifully thin atmosphere that makes landing stuff a huge challenge because there's little to 'grab onto' as you come hurtling in from orbit.

Small scientific robots and rovers are already pushing the limits of what we can get to the martian surface in one piece. What's really needed is the ability to bring a whole launch vehicle down, with tons and tons of payload.

...which is exactly what we've seen SpaceX do once again.