This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Humanity has been reshaping Earth’s ecosystems for millennia in two basic ways. We engage in large-scale conversion of natural habitats to agricultural crops and cities to feed and house our burgeoning population. And in more subtle ways we change the state of natural systems through activities like hunting, logging, and fire management.

Both large-scale habitat conversion and local habitat degradation can have serious impacts on how nature functions and the species it is able to maintain. Take, for example, the massive decline due to hunting of bison across North America in the 19th century. The loss of bison dramatically degraded the functioning of prairie ecosystems they kept healthy through grazing and other biological functions.

Too many ecosystems today find themselves in a state of rapid change as “keystone” species—so called for the outsized ecological engineering role they play in their habitats—are being lost.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

As both the number and wealth of people on Earth has skyrocketed over the past few decades, this reshaping of nature has reached new heights. Some of the damage has been balanced by the growing concentration of people in cities, where their immediate impact on wild places is reduced. Nonetheless, we are now extracting natural resources, building infrastructures, and converting natural habitats in places and at rates that are entirely unprecedented.

We know that this reshaping comes at a cost. The ecological goods and services (such as clean water, storm defense, and carbon sequestration) provided by nature underpin all our social and economic systems. As nature gets degraded, so do these ecosystem services. Yet there has been persistent uncertainty about the extent of the ‘Human Footprint’ across Earth and what this means for the future of nature and humanity.

Powerful computers working through deluges of data from a network of satellites have enabled us to carefully document most of the large-scale impacts of the human footprint, such as the conversion of forest lands to agriculture.

The problem has been that many lower intensity forms of our footprint, such as our extensive networks of roads, power lines, and water irrigation (known as linear infrastructures), along with grazing lands for cattle and sheep, are more insidious than outright habitat conversion and are poorly detected from even the best types of space-borne satellites.

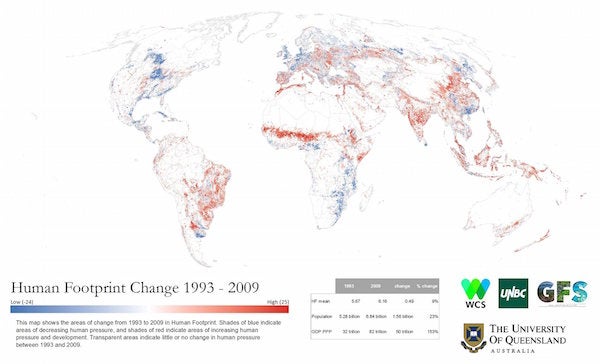

We and several colleagues recently mapped eight factors related to human pressure – including where we live, the land we can access, and the crops we grow—using data from a range of satellite and ‘bottom up’ sources such as road-mapping inventories. The result, the most up-to-date and complete picture of the human footprint on terrestrial earth, has been published this week in the journal Nature Communications.

Credit: Oscar Venter and James Watson

The maps show that the global impact of human activities on the natural environment is extensive, with three quarters of the planet now significantly altered by humanity. Critically, 97 percent of the most species-rich places on Earth have been seriously altered by humans, which is why we now face a biodiversity extinction crisis that is continually getting worse.

Our maps are also unique in that they go back to 1993. Since then the human footprint has grown by nearly 10 percent. To put this in to perspective, over the same period the human population grew by 23 percent and the size of the global economy grew by 153 percent.

Taken together, this suggests that there has been a trend toward fewer impacts per person and significantly fewer impacts per dollar of economic activity over the past two decades. At the global scale at least, we would appear to be increasing our efficiency with how we manage our impacts on the environment.

We found that 26 countries managed to significantly grow the size of their economies over the last two decades while shrinking their environmental impacts of land use and infrastructure. These countries, including for example Mexico and Sweden, tended to have good governance structures and higher rates of urbanization.

It is tempting to conclude that these countries have managed to decouple economic growth from environmental impacts. If so, those efforts would be truly transformational and we would have much to learn from them. Yet further analyses are required to determine if some countries have simply shifted their impacts offshore by importing their goods and raw materials.

Log barge, Borneo. Credit: Oscar Venter

We believe there are some broad lessons in all of this. Where societies fail to establish strong governance structures capable of managing human impacts on nature for the common good, our demands on ecosystems will continue to accelerate, ultimately undermining their long-term stability. Thus will result widespread biodiversity declines and serious reductions in the benefits humans receive from natural systems.

But where societies promote honest government and actively encourage the concentration of people into cities so their housing and infrastructure needs are not spread across the wider landscape, there is hope of achieving the bottom line of a healthy environment and economic prosperity. Which world would you rather live in?