This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

XIANGYANG, China—This factory located in a quiet island of central China’s Xiangyang city probably won’t grab your attention. Its stainless steel complex and three-story office building look similar to any other. But don’t be fooled by appearances. The plant here holds a secret that has lured more than 100 Chinese mayors to pay their respects and uncover how they can replicate its success.

On any given day, the factory eats up several hundred tons of human excreta and other waste—a smelly, hazardous slurry called sludge—and spits out enough clean energy to fuel 400 cars. In a country struggling with pollution from massive quantities of untreated sludge and seeking new sources of clean energy, policymakers want to get more sludge-to-energy projects up and running soon.

Already, about 400 miles east of the factory, Hefei is putting together its first experiment converting municipal sludge into energy. Beijing has also rolled out a plan to tap into the energy potential of sludge, along with other cities such as Chengdu, Changsha, and Chongqing.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

But before this project, none could be sure that such an effort could be financially and environmentally viable in China.

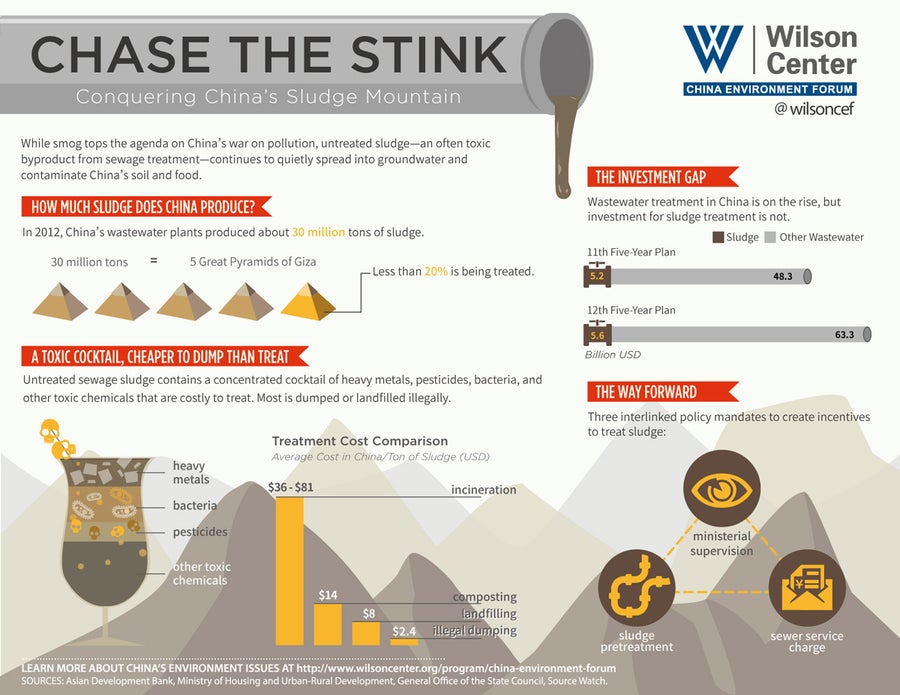

Sludge is a rising threat to China’s environment. As the number of wastewater treatment plants in the country has increased in response to water pollution, so has the volume of the resulting byproduct. According to recent estimates by Essence Securities, 35 million tons of sludge were produced by Chinese wastewater treatment plants in 2015, a 16 percent increase from the previous year.

Sludge Mountains

Municipal sludge is often dumped into landfills or even back into the environment untreated. According to one study, by Tsinghua University, nearly half is used as fertilizer by farmers. If untreated, sludge can contaminate the soil, air, and groundwater. Toxic chemicals become part of the food chain, making their way onto dining room tables.

Chinese leaders are aware of the problem. Last year, the central government mandated prefecture-level cities make 90 percent of their sludge toxic-free by 2020—up from the current requirement of 70 percent—and employ proper disposal solutions. In the past, though, similar efforts have flopped.

Click to enlarge.

Chinese cities have tried to build sludge incinerators or burn the byproduct as an alternative fuel in coal-fired power stations. While helping to reduce sludge in the short term, such burning is expensive and requires a great deal of energy. “Sludge has a high level of water content, even after dehydrating,” explains Nawon Kim, an environment specialist with the Asian Development Bank. “In order to prepare it for burning, it requires a lot of additional energy to dry.”

Recycling nutrient-rich sludge into compost is not a quick fix either. China’s Ministry of Agriculture has banned sludge-generated compost from being used on farmlands due to concerns over heavy metal contamination. And while the country’s tree growers welcome the use of sludge, industry players say the market demand is limited.

Necessity, the Mother of Innovation

For now, much of China’s sludge ends up in landfills, bumping up against the limit of increasingly scarce land resources and creating environmental hazards. In 2009, huge quantities of sludge came bursting up from the ground in Shenzhen after landfilling put so much pressure on the water table it erupted. The pollution flowed into a nearby river and all the way to neighboring Hong Kong.

But for TOVEN, a Wuhan-headquartered Chinese firm specializing in waste-to-energy technology, these challenges have provided an opportunity. In 2011, after Xiangyang failed in an initial attempt to turn its sludge into compost, the company pitched municipal officials on a completely different approach. Thus began a smelly and slippery five-year journey.

“Where we are standing now was all covered by sludge back in 2011,” Dou Wenlong, the company executive, tells me in his marbled conference room.

“Sludge is basically toilet waste,” Dou continues. “At that time, about 150,000 tons of sludge piled up here—all left by the previous compost project operator. Just imagine being surrounded by 150,000 tons of toilet waste. The smell was unbearable. I couldn’t eat anything when I first came.”

After two months testing sludge samples and adjusting anaerobic digestion techniques, Dou and his team got used to the foul odor, he said. However, the challenges of working at the site continued.

Credit: Courtesy of TOVEN

During the company’s first few years, flies assailed engineers throughout the day. And when Dou and others walked outside, they had to watch where they stepped. Once sludge begins to dry, it forms a semi-solid surface that vegetation can take root in, luring people into thinking it is safe. Dou remembers making many mistakes in the early years and stepping into semi-solid sludge sometimes reaching up to the knee. “I lost so many of my pants and shoes,” Dou says, with a laugh.

There were technical challenges too. Sludge in China contains low organic matter levels—about 40 to 50 percent—due to sewage systems that include both municipal stormwater runoff and wastewater from households. In comparison, international sludge-to-energy plants frequently have material that’s up to 70 percent organic matter. Organic matter is a key ingredient for producing methane, which can later be captured to generate power.

Dou, who visited almost all the sludge treatment plants in Europe, knew that adopting strategies such like preheating solid waste could help increase the levels of organic matter and boost energy production. But the technology to implement such a solution did not exist in China at the time, and the company did not want to rely on imports. Dou and his team decided to develop their own equipment and learn the hard way.

“Once we were looking for a suitable pressure compensation, and we had tested dozens, if not hundreds, of pressure compensations already,” Dou recalls about one crucial component. “None of these met our expectation, but testing more devices meant spending more money. It was a risky decision. We were really stressed out as we knew some decisions could cost the company.”

An Extra Ingredient

Luckily their efforts paid off, thanks to some ingenious engineering and a surprising ally: Xiangyang’s restaurants.

Since the project went online in 2012, not only has the plant treated all the aged sludge that piled high at the site when Dou and his staff first arrived, but it also handles fresh sludge and kitchen waste.

Every day, sludge generated by the Xiangyang’s 2 million residents is delivered here by truck or pipeline. The plant mixes the sludge with kitchen waste collected from restaurants to increase organic matter, heats the mixture to temperatures as high as 130 degrees Celsius (266 degrees Fahrenheit), and sends it through a process called co-digestion.

Two 20-meter high, silver-colored anaerobic digestion tanks inhale 450 tons of sludge and kitchen waste and exhale at least 12,000 cubic meters of methane. The factory then burns half of the methane to power its operation and processes the rest into compressed natural gas.

The compressed natural gas is sold at a nearby gas station to local taxi drivers, helping to meet the city’s growing demand for cleaner-burning transportation fuels. What’s left from the solid waste is either sterilized to be used in fertilizer or converted into biochar, an alternative soil used for potted trees.

Stretching the Dollar

“This is an efficient way to get rid of sludge in the context of China,” says Zhong Lijin, an expert at the Beijing office of the World Resources Institute, a think tank based in Washington, DC.

Zhong and her colleagues conducted a case study on the Xiangyang sludge-to-energy project in 2013. Their findings, published in December 2015, show that compared to other disposal methods, such as turning sludge into compost or burning it at incineration facilities, the methane conversion costs less while at the same time generating commercially viable products.

Dou declined to disclose the project’s revenue, but said it is profitable. He added that some benefits go beyond the company’s balance sheet.

As Dou explained, the island where the facility is located used to be a pariah for investment because of its rotten egg smell. But since the facility started operating, the pollution has begun to fade. Last year, investors from Hong Kong unveiled a $1.7 billion development plan for Xiangyang, the majority of which is intended for luxury resorts, golf courses, and marina clubs on the island.

“You wanted to know our revenue? I think it’s fair to say $1.7 billion,” Dou says.

There are environmental benefits as well. Until his company treated all the aged sludge in 2015, Dou said some of it was just 50 meters (164 feet) away from Han River, an important tributary of the Yangtze. Xiangyang is along the central route of China’s South-North Water Transfer Project, a multi-decade infrastructure project that will channel 44.8 billion cubic meters of freshwater annually from the Yangtze River in southern China to the more arid and industrialized north. Protecting these waters from sludge runoff reduces the treatment and energy costs to clean it—important savings in a country with growing water constraints.

Change on the Horizon?

The World Resources Institute report says compared with landfill and incineration methods for dealing with sludge, the plant could reduce greenhouse gas emissions more than 95 percent over the course of its lifetime.

If 10 percent of the sludge generated in China last year was treated in the same way, it would have reduced greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to 380 million tons of carbon dioxide, roughly equal to Ukraine’s total emissions in 2012.

As promising as this may sound, replicating the Xiangyang plant elsewhere remains a challenge. Experts say that it is conventional wisdom that converting sludge into energy is unprofitable in China, due to low organic matter levels, and it takes time for industry players to change their minds.

A lack of supportive policies from the central government is another barrier. Dou said that unlike wastewater treatment, the regulation for sludge treatment does not come with a penalty and is therefore hard to enforce. Local policymakers have little incentive, in terms of their own promotion up the party ladder, to pay attention.

Even though current regulations require at least 70 percent of sludge in Chinese cities to be treated, media reports, from Beijing to Shanghai continue to uncover evidence they are being ignored. In Wuhan, for instance, un-supervised dumping turned a piece of postcard-like forestland into quagmires the size of football pitches.

But change may be on the horizon. The project in Xiangyang demonstrates that sludge-to-energy plants can be successful in China. And in an article published earlier this month by the newspaper Southern Weekly, Zhang Yue, an official with the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development said party leaders are considering including sludge treatment in municipal government pollution reduction targets, with new regulations to be released soon.

This article is reproduced with permission from New Security Beat. The article was first published by the Wilson Center's China Environment Forum on May 31, 2016.