This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

“Sexual aversion and loss of sexual enjoyment.” “Flatulence and related conditions.” “Mouth breathing.” These are actual recorded causes of death for at least one person in the Centers for Disease Control registry that aggregates mortality information from all 50 states.

I found this out only by accident while researching which diseases are responsible for the most lost years of life. When I reviewed the dataset (download my data and code here), the usual suspects topped the list, including lung cancer and heart disease. But the dataset contained thousands of other listings. Curious, I went straight to the bottom, to the rarest causes of death.

It turns out there are a lot of strange reasons listed as “underlying cause of death,” including:

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Muscle strain

Emotionally unstable personality disorder

Other amnesia

Other specified rheumatoid arthritis

Allergic rhinitis, unspecified

Spontaneous rupture of other tendons

Restlessness and agitation

Pathological fire-setting

Pain in joint

Mouth breathing

Separation anxiety disorder of childhood

Other bursitis of elbow

Mild mental retardation

Other migraine

Immobility

Pain in limb

Social phobias

Low back pain

Needless to say, none of these conditions can possibly be the direct cause of death. No one dies from restlessness, let alone from flatulence. Perplexed, I emailed the CDC. One official said it was “astonishing” to see reasons like “mouth breathing” on the list. Another said that people who fill out death certificates sometimes use “very unique” terms.

These flawed diagnoses are no laughing matter, however. At a time when some people herald the value of big data, it’s important to remember that mistakes and sloppy records can lead to the misallocation of resources, or worse. So I asked Dr. Dwayne Wolf, Deputy Chief Medical Examiner at the Harris County Institute of Forensic Sciences in Houston, Texas what is going on.

The first reason for the odd fatalities, according to Wolf, is that medical schools provide “minimal training” on how to complete a death certificate. Even skilled physicians might err in how they record a person’s cause of death. Worse, if a physician has not added any information about the cause of death, and the record shows only that the person was originally hospitalized for “low back pain,” then “low back pain” can show up as the official cause of death.

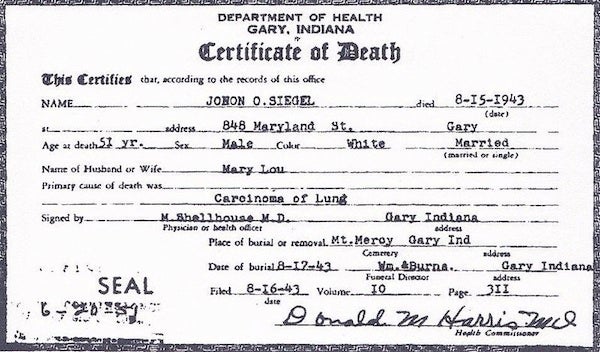

1943 death certificate of John Otto Siegel, presumably with the cause of death noted correctly. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Second, coroners can be elected with no medical training whatsoever. In Texas, for example, only a handful of counties have medical examiners. In the rest of the state, an elected justice of the peace supervises death investigations. Wolf said these individuals are often “flying by the seat of their pants” due to their lack of medical training. As a National Academy of Sciences report pointed out, “The disconnect between the determination a medical professional may make regarding the cause and manner of death and what the coroner may independently decide and certify . . . remains the weakest link in the process.”

It’s not just Texas. A Bureau of Justice Statistics report from 2007 counted 1,590 county coroners serving in 27 states, and noted that, “coroners may be lay persons.” Indeed, a few years back, an 18-year-old girl in Indiana made the news for becoming the state’s youngest coroner while still in high school.

Worse still perhaps, Wolf told me that death certificates are generally “very inaccurate” even when it comes to the “big killers” like heart disease and cancer. “There are cases where somebody with lung cancer gets listed with bronchopneumonia as the cause of death,” says Wolf, explaining that whoever fills out a death certificate may list a related medical complication rather than the true underlying cause of death.

A recent survey of several hundred medical residents in New York City found that only a third believed in the accuracy of cause-of-death reporting. A 2014 New Yorker article reported that an in-depth investigation of 2,683 deceased participants in the Framingham Heart Study suggested that “national mortality statistics, which are based on death certificate data, may overestimate the frequency of coronary heart disease by 7.9 percent to 24.3 percent overall and by as much as two-fold in older persons.” And a study from the American Academy of Neurology in 2014 found that “deaths from Alzheimer’s disease far exceed the numbers reported by the CDC and those listed on death certificates.”

These systematic inaccuracies should give us pause about the much-heralded era of “big data” in medicine. How can anyone use this information to research how medical treatments or the effect of nutrition affect mortality when something as basic as the cause of death might be misreported? And without reliable research, how can society know where to allocate precious research dollars related to health and mortality? If big data is going to be of any use to medical professional and public, better training and oversight is needed for those who compile such records, and anyone seeking to use the information must remember that, as The New York Times put it, some “janitor work” is required in order to draw insights.

After all, we don’t want to mistakenly invest large sums in the fight against mouth breathing.