This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Climate change and sea level rise are going to hit three Pacific island seabird species hard by the year 2100, threatening them with rapid population declines.

The risk won’t come directly from rising tides but from storms that will be intensified by climate change and higher sea levels due to melting glacial ice. By the end of the century much stronger waves are expected to pound nesting sites, flood habitats and displace hundreds of thousands of birds, according to research published this week in PLoS ONE.

The study—led by researchers from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS)—examined 13 seabird species which nest on 58 low-lying Pacific islands protected by U.S. Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, including famous areas such as Midway Atoll. Although all of those species will experience sea level rise and its associated risks, the team found, three currently common species will fare the worst: the Laysan albatross (Phoebastria immutabilis), black-footed albatross (P. nigripes) and Bonin petrel (Pterodroma hypoleuca).

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The Bonin petrel currently is considered a species of least concern by BirdLife International, with a worldwide population of about a million individuals. The two albatrosses are both listed as species of “near concern.” The Laysan species is estimated at about 1.7 million individuals and the black-footed albatross has an estimated population of about 129,000.

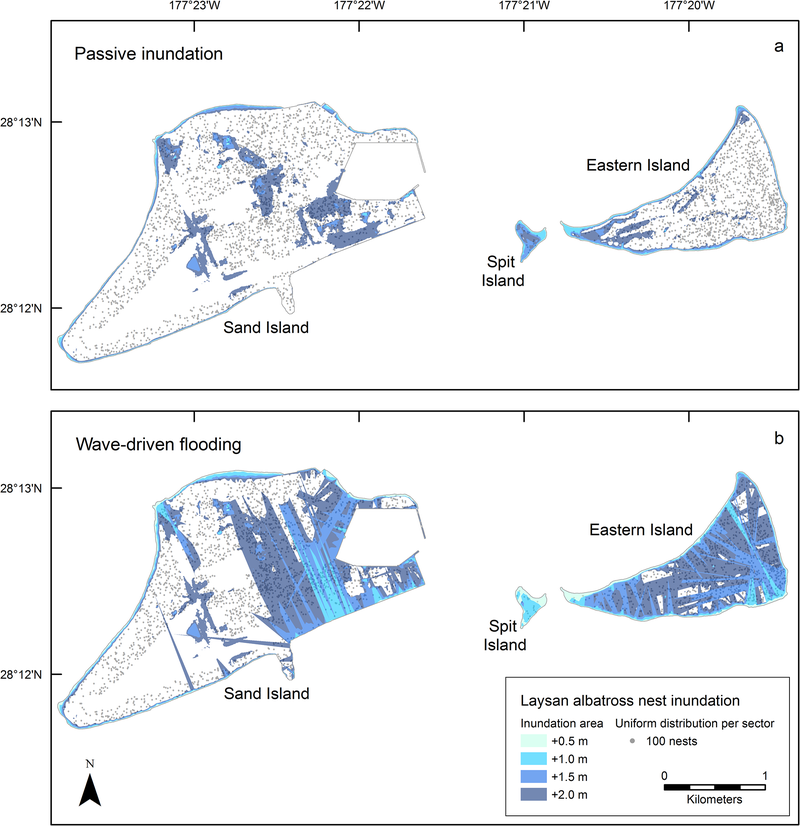

The numbers for all three of those species will drop as sea levels rise. The researchers focused on the impact of four possible sea level–rise scenarios on birds living on three islands in the Midway Atoll. Under the worst of the scenarios 60 percent of albatross and 40 percent of petrel nests would be flooded, the analysis revealed. Compounding matters, nesting season coincides with storm season’s peak, when the weather drives higher waves and flooding.

The flooding would also displace more than 600,000 breeding birds from the three species. Most of these birds have no available alternative breeding sites, so this combination of lost nests, reduced reproductive success and displacement could quickly endanger the species’ long-term potential for survival.

The natural landscape—as well as some of its unnatural components—also are predicted to play a destructive role. The islands within the Midway Atoll today have an average elevation of just 3.2 meters above sea level. The worst model predicts a seal level rise of two meters, making the current low-level habitat inhospitable, to say the least. The birds can’t simply move to higher elevations either, because invasive bird-eating predators such as rats and feral cats already live there. (Humans aren’t a problem for the birds, however; the collective population on these three studied islands is about 60 people.)

Lead researcher Michelle Reynolds from the USGS said in a prepared statement that the big surprise from the study was that the most abundant species in the islands would be the most sensitive to the effects of sea level rise. She and her colleagues suggest that now is the time to start planning for future climate change effects and to restore seabird habitat in higher elevations by killing or fending off predators in order to give these Pacific island birds one last place to run to and raise their families once the waves come crashing in.

Photo: Black-footed albatross with chick, by Wieteke Holthuijzen/USGS

Previously in Extinction Countdown: