This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

It took Olivia Hallisey, 17, one year to find a possible solution for an intractable public health problem: the lack of a rapid, portable, early diagnostic test for Ebola and other diseases.

Hallisey, a high-school junior, lives in Greenwich, Conn. –- far removed, economically, from the West African communities hit by last year’s Ebola outbreak. After reading reports of how quickly Ebola was spreading through Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, she felt compelled to help.

With the encouragement of her science research teacher at Greenwich High School, Andrew Bramante, Hallisey began reading up on diagnostic tests. She found that many require electricity and refrigeration -- both in short supply in rural villages - and take hours or days to return results. Many patients get their diagnoses too late – once they are already gravely ill and have transmitted the virus to others.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“The best way to limit Ebola’s spread is if you can isolate someone before they’re contagious,” said Hallisey.

She read online about a silk fiber derivative that can keep proteins stable without refrigeration. Common tests like the ELISA, on which Hallisey based her project, rely on mixtures of protein and water to trigger the chemical reactions that lead to positive or negative results. Typically, these solutions, known as reagents, need to be refrigerated. Hallisey used the silk derivative to make her reagents and found that the test performed just as well after one week with no refrigeration.

She then scrapped the ELISA’s plastic well-plate design and mounted test strips on a laser-cut paper card that is portable, simple to read, and returns results within 30 minutes.

“She did what I love to see and what I find so inspiring: She looked at what exists and then took a leap,” said Mariette DiChristina, editor-in-chief and senior vice president of Scientific American and chief judge at the Google Science Fair.

Hallisey credits the adults in her life for juggling their busy schedules to help her finish the project. Two scientists at Tufts University in Boston who developed the liquid silk formulation, Fiorenzo Omenetto and Benedetto Marelli, agreed to help Hallisey after she took an interest in their work and emailed them for advice.

Hallisey’s father drove her to Boston about 10 times so she could use a laser cutter that the Silklab at Tufts made available.

“We would get up early some mornings, get to Boston about 10, use the laser cutter and then run home so I could get to swim practice on time,” said Hallisey. “It was a crazy experience, but you can’t turn down an opportunity like that.”

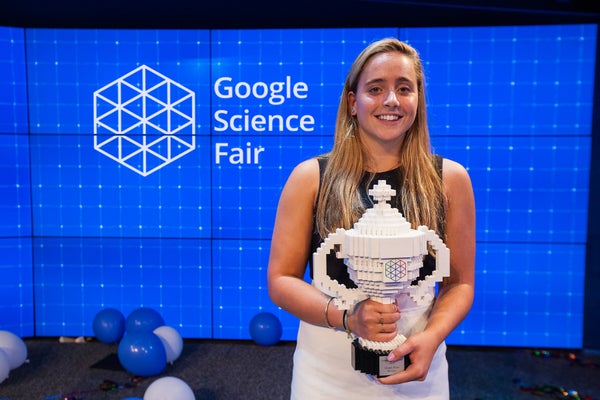

Hallisey won the Grand Prize at the Google Science Fair, which includes $50,000 in scholarship funding. To read more about her project, visit the Google Science Fair Web site.

Putting Corn Cobs to Work:

Heaps of corn cobs piled along roadsides in her native India inspired Lalita Prasida Sripada Srisai, 14, to design a new type of water filtration system.

The teen lives in a small town in the Eastern Indian state of Odisha, and she likes to stroll through farming villages and observe rural life.

“I used to wonder what to do with these corn cobs, and why are they just thrown out,” she said.

Corn is India’s third biggest crop and a popular street food.

One day, Srisai collected a few muddy, discarded cobs from a street vendor, brought them home and put them in a bucket of water to rinse them. When she awoke the next morning, she saw that the water was clean. “It was really, really amazing, and so I got the idea for purifying water in this way,” said Srisai.

Srisai created a filter that uses corn cobs in multiple forms. First, wastewater flows through long pieces of corn cob, then smaller pieces of corn cob, then powdered corn cob, activated charcoal made from corn cobs, and, finally, fine sand. The filter can trap metals such as lead, cadmium, and chromium, according to her test results.

“My main objective was to treat wastewater at its source before releasing it into aquatic areas, so that aquatic lifeforms would be protected,” she said.

Srisai won the Google Science Fair’s Community Impact Award, sponsored by Scientific American. The award comes with $10,000 and a year of mentorship to help develop her project.

Krtin Nithiyanandam, 15, from London, won a second Scientific American-sponsored award, the Innovator Award, for a new method to detect the earliest signs of Alzheimer's Disease. Read about his project and the work of other finalists here.

.jpg?w=600)

Srisai shows her project to Google Science Fair judges. Image: Andrew Federman, Google