This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Did you hear about the seventeen year old girl who was pushed into an open manhole by bullies in her school? Her name was Carmen and she had made up her mind to tell someone that she was being bullied, but she didn't get a chance. During a fire drill the bullies kept crowding her and crowding her; and then one of them pushed her, causing her to trip and fall into the open sewer. Her tormentors didn't tell anyone until her name was called during roll. They were looking to embarrass her—and they were satisfied with the laugh they got when the other kids heard Carmen was down in the sewer. But there wasn't anything to laugh about. Her face had been scraped off by the ladder rungs on her way down and she had broken her neck. Carmen was dead.

The police questioned everyone following her death. The bullies said they saw her fall down the manhole—unassisted—and the police believed them. Carmen's death was ruled an accident and everyone went about their business ... until the emails started. The subject line read "They pushed her," and included a message that claimed Carmen had not fallen into the sewer. it encouraged the guilty parties to come forward. None did, of course, and a few days later one of Carmen's tormentors heard strange laughter while she was taking a shower. Later that night, she disappeared and was found lying at the bottom of the sewer with her neck broken and her face torn off just as Carmen's had been.

One by one, all of the bullies met the same fate. But so did many of Carmen's classmates who believed she had fallen. Some say she's still on the hunt for people who don't believe her story. She'll get to you from a toilet, a shower, a sink, or a drain, and you'll find yourself lying at the bottom of a sewer, paralyzed, until her spirit rips your face off. So be careful who you bully—or you may have to deal with Carmen.

Oh, and by the way, if you don't repost this saying "They hurt her," Carmen will come for you.

It happened to sixteen year old David Gregory who laughed at this story and thought it was a joke.

I have to admit that this particular chain letter hooked me with the first sentence. I didn’t share it as requested—though I guess I am sharing it here—but given the frequency of stories about bullying and the negative impact of bullies, the first sentence didn’t seem entirely unbelievable. That, of course, is the secret to the longevity of the chain letter phenomenon: the messages they carry are relatable. They hit the right chord of shock, or trigger the right degree of anxiety, which prompts the reader to share the stories or information they contain. To this end, chain letters are actually really well suited to social media because so little effort on the part of the reader is required to pass them on. And the transparency offered by sharing or liking adds a degree of authenticity that is necessary to their survival.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Same story, different day.

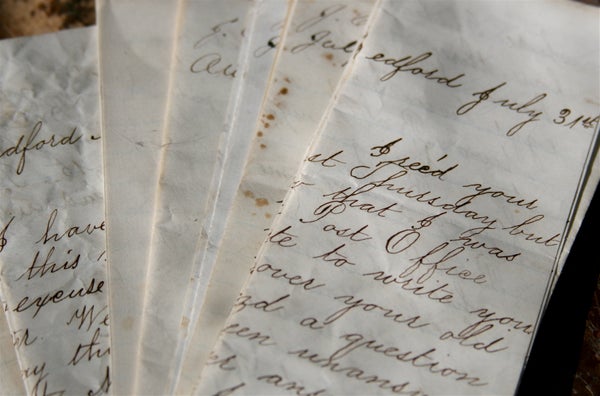

Chain letters are formulaic by nature. Even in their most basic form they offer the reader some benefit in exchange for learning or sharing the contents of the text. The earliest examples of chain letters promised spiritual or divine recognition. Examples from the archive [pdf] amassed by mathematician and folklorist Daniel W. VanArsdale include a passage from the ancient Egyptian Book of That Which is in the Underworld, which promises the reader a place on the boat of Ra in exchange for copying an image contained within, and numerous dharani, that assure the would-be preservationist of protection (from various things) if he would find a way to ensure the text was passed on.

This theme of protection and divine intervention persisted. Documents claiming a divine provenance, known as "Letters from Heaven," are littered throughout history and can be found in Greek, Arabic and Ethiopian traditions. In recent history, these types of chain letters have been more commonly tied to Christianity. And while VanArsdale maintains these are not "true" chain letters, they contain many of the same traits as their cousins. For example, they begin in such a way as to establish themselves as believable:

This letter was written by Jesus Christ, and found under a great stone round and large at the foot of the cross. Upon the stone was engraved, "Blessed is he that shall turn me over." All people that saw it, prayed to God earnestly, desired that he would make this writing known unto them, and that they might not attempt in vain to turn it over. In the mean time there came out a little child, about six or seven years of age, and turned it over without assistance, to the admiration of every person who was standing by. It was carried to the city of Iconium, and there published by a person belonging to the Lady Cuba.

They also take great pains to enumerate the dangers that could befall someone who fails to pass the letter on:

And he that hath a copy of this my own letter, written with my own hand, and spoken with my own mouth, and keepeth it without publishing it to others shall not prosper; but he that publisheth it to others, shall be blessed of me, and though his sins be in number as the stars of the sky, and he believe in this he shall be pardoned; and if he believe not in this writing, and this commandment, I will send my own plagues upon him, and consume both him and his children, and his cattle.

And they offer protection and blessings if the letter is passed on:

And whosoever shall have a copy of this letter, written with my own hand, and keep it in their houses nothing shall hurt them, neither lightning, pestilence, nor thunder, shall do them any hurt, and if a woman be with child, and in labour, and a copy of this letter be about her, and she firmly put her trust in me, she shall safely be delivered of her birth.

If we look at the example of the chain letter that we began with, the formula persists:

The story names the protagonist, which helps personify her. The story also places her in a familiar context causing the reader to identify with her. These factors contribute to it’s potential believability.

The danger in not sharing the story is clearly stated: Carmen will come for you. And this is validated by several “accounts” where she has wrought her vengeance.

It offers the reader protection from Carmen in exchange for sharing the letter.

These thematic elements are present in most categories of chain letters, which have branched out to include tantalizing suggestions of luck, encourage the exchange of goods, enact change, and set records. However, they are also present in modern day chain letters as well, which have adapted to the online media in which they have taken up residence. Just as there are many varieties of traditional chain letters, in social media, we’re seeing the emergence of a variety of chain posts.

Survival of the fittest.

For a long time the survival of chain letters required genuine effort. Their senders needed to invest in them to allow them to pass on to the next person: copying and sharing a chain letter meant copying the letter by hand, acquiring postage, and actually mailing it. For these reasons chain letters needed to be explicit in their instructions ("Send this to 12 of your friends within five days or else …”) because there was no guarantee that they would actually be passed on. This effort contributed to their power. The anonymity of the process helped: After all, for someone to take the time to pass on a chain letter meant that they believed and if they believed, then shouldn’t you?

The introduction of the photocopier in the 1950s diluted this power just a bit. Though it facilitated the spread of chain letters, their increasing ubiquity helped to make the intended recipient somewhat immune to their mystique. Anonymity became a hindrance. A handwritten letter from an unknown source still carries something of the original author in it, whereas a photocopied document lacks this sense of individuality. Even as chain letters found a tool through which they could maximize their chances of survival, the mechanization of production diminished their connection with recipients.

It also became harder to take them seriously. We were growing accustomed to recognizing sources of content. The rise of communicative technologies changed the we thought about and interacted with information. These channels placed the individual within a network bound by shared experiences. The content we consumed carried broader social meanings of belonging. This is especially true in the online world, where it’s not a secret that we author a representation of ourselves through the material we like and share.

Reflections of self.

Chain letters needed to adapt. Social media offered a high potential for sharing content, but removed the condition of anonymity from participation. The result is that chain posts become a way to help author self— they share something about us when choose to participate.

For example, they can help us connect with each other around shared interests:

Or they can help us share and affirm social beliefs:

The chain letter formula may not be as apparent here, but it still exists. By tackling a mainstream topic, it establishes relevance and believability. It carries the undertone of separating people if they disagree with the above sentiment, in the same way it promotes sharing to establish connections.

Chain posts still offer a degree of protection—only in this case, it’s the protection of self. They play into the ways in which we form identities online; they help us shape the personhood we would like to present and provide a visible means by which we affirm our connection to our networks. For example, if your friend Katie likes a post about Veterans, you learn something about her. You can participate in this act of authorship by commenting or liking the post as well. In the case of chain letters, the effects of this visibility is two-fold: while chain letters derive a degree of authenticity from being visibly liked, so too does the reader by establishing and connecting themselves with an identifiable marker.

Preteens seem particularly inclined to this method of online identity formation. They’re not using chain posts to solidify the identities they have crafted, rather, they’re using chain posts to actively construct their sense of who they are by asking for feedback from friends:

In this instance, the post asks readers to Like My Status (LMS) to help continue the feedback cycle. Social networks allow preteens to ask questions about self, and then step back and allow the community to weigh in to confirm or dispute the feedback they’ve been given. There are many dangers to this approach, but it is a facet of navigating identity formation in an online world.

The more things change.

Chain letters in social media may look differently from traditional chain letters, but this idea of how they feed into a sense of self seems to be a consistent trait. Even when people were sharing them under the guise of anonymity, part of the reason they worked is because individuals were able to connect to their messaging. In the case of exchange rings, individuals are looking to affirm their place within the network; with the Letters from Heaven, participating meant continuing a belief system. These actions contribute to a sense of self.

So, do you have a favorite that you've seen? Or a chain letter story to share? You should probably tell us in the comments ... because you never know.

Have something to say? Comments have been disabled on Anthropology in Practice, but you can always join the community on Facebook.

--

You might also like:

Is email one of the last private spaces online?

What do those temporary Facebook profiles really mean?

--