This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

The Allied offensive in the Battle of the Somme had been going on for about 20 weeks by the time this article was published 100 years ago today. A combined total of close to 300,000 soldiers from both sides had perished. The consensus, then and now, (with many dissenters!), is that the attack, despite the horrific losses, was considered a strategic victory by those tasked with winning the war. It achieved the primary objective of soaking up German resources and reducing the ferocity of the German assault on Verdun, which had risked causing the complete collapse of the French army. That strategy may not have been emphasized publicly by those in charge, as it would have admitted that the French were in dire straits, but aspects of the strategy were guessed at and acknowledged. Here’s what Scientific American said back then:

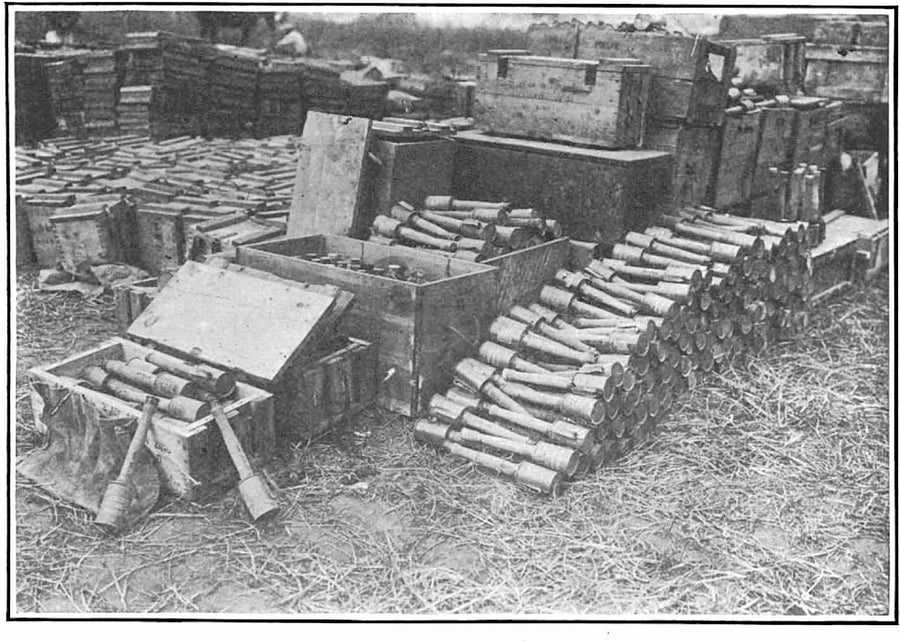

“It is the claim of the Franco-British army, which now for nearly four months has been making a practically continuous drive into the German line on the Somme, that the extent of their success is not to be measured in terms of territory taken so much as in the degree to which it is holding the flower of the German army in its front, and breaking it down in munitionment, manpower and morale. The steady advance of the Allies in this four months' continuous battle has been marked by a great slaughter of the enemy and considerable captures of heavy and light guns, machine-guns, and the various implements of trench warfare; also the toll of prisoners has been large. The total capture to date has been between 70,000 and 80,000 prisoners, and some 400 guns, big and little. The photographs accompanying this article show some of this captured material.”

Perhaps this look at the material losses to the Germans avoided the more dismal question of whether the number of men killed or wounded on either side could justify the battle. In any event, the piles of grenades and weapons depicted look like they would have been sorely missed by the enemy.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Or not.

I count perhaps a thousand stick-handled grenades. That might have been the equivalent of one hour’s industrial output. Other images in this series show makeshift or obsolete equipment.

“War booty” includes stacks and boxes of grenades—a miniscule fraction of the industrial output of the fighting nations. Credit: Scientific American, November 11, 1916

Regardless, military censors had a firm lock on the flow of information from the front, and these photographs survived censorship perhaps because they were seen to have propaganda value.

In historical terms, though, the Germans were shaken on the Somme. The sheer number of soldiers and the weight of explosives hurled at them demonstrated the vast demographic and industrial capacity the Allies had harnessed and the determination to use it. Alexander Watson’s finely researched and thoughtful book Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I (Basic Books, 2014) perhaps put it best: “The Somme battle’s most damaging impact on the German army was in fact not material but psychological .... not just the generals but their soldiers too new knew how powerful their enemies were and how close they had come to being overwhelmed.”

-

Our full archive of the war, called Scientific American Chronicles: World War I, has many articles from 1914–1918 on technological developments in the First World War. It is available for purchase at www.scientificamerican.com/products/world-war-i/