This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Yesterday, baseball fans celebrated Opening Day of the 2011 season. In honor of that, I wanted to share an impressive and interesting invention featured in the September 28, 1912, issue of Scientific American: the Nokes Electrascore.

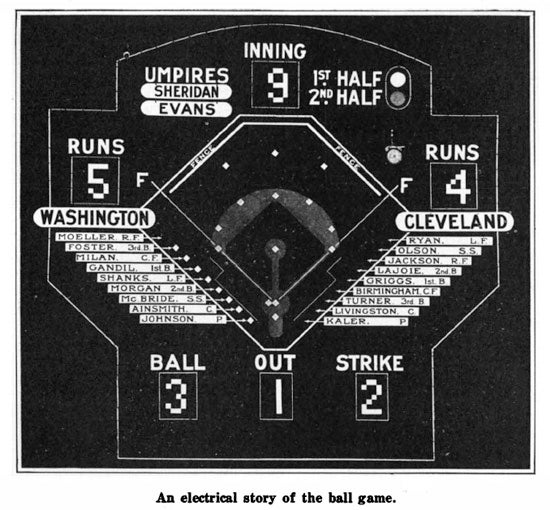

The Electrascore was a giant electrical scoreboard that projected a baseball game’s action. It measured 16 feet square with a baseball field in the center measuring eight feet square. The field was made with green copper wire while the diamond was made with brown. There were over 1,500 lights of four candle power beneath the field, differently colored to distinguish between the batting team (white), the team in the field (green), and the ball (red). Instead of indicating only the score, batter, inning, etcetera, and having a base light up when a player reached it, the Electrascore showed lines of light to depict the movements of the players and the ball. For example, each player of the team up at bat had a “lightman” next to his name that would move from the dugout to the batter’s box, and if he was lucky, from one base to the next.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

When I first read this article, I assumed the scoreboard hung inside of a baseball stadium and was used to give fans with bad seats an easier way to follow the game. However, after further researching Nokes’ invention, I found out the reason it was so spectacular at the time—these scoreboards were made to be hung outside of newspaper buildings or inside theaters to allow fans who were not at the game to experience the action almost live. Telegraphic connections allowed the plays of the game to come direct from the baseball field or a local wireless station.

“In other devices of this character, the aim has been to give the result or final of a movement of a man from base to base or the course of the ball from the pitcher to the batter or one man to another. As to the details which bring about this result, the baseball fan at the scoreboard is ignorant until he reads the newspaper. The Electrascore, however, accomplishes this through the maze of lights under the screen field. It is the feature that causes the fascination for the counterfeit game.”

Of course, today we have the luxury of watching baseball games on television when we can’t be at the stadium. Yesterday, however, I found myself without a television or radio and didn’t want to pay to watch or hear my favorite team play their first game of the season live on my computer. Luckily, I was able to follow the action (with a bit of a delay) on a baseball news site that used avatars of players to depict a virtual game. It didn’t feel like too far of a stretch from being part of a crowd gathered in front of a newspaper building watching the Electrascore 100 years ago.

I hope all the fans (especially of the Yankees) have a great season. Play ball!