This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

In March 1916 Francisco “Pancho” Villa, a leader of one of the revolutionary factions in Mexico, crossed the Mexico–U.S. border and attacked a detachment of the 13th U.S. Cavalry in the border town of Columbus, New Mexico. The town was burned, military stores were taken, 18 Americans were killed, and 90 of Villa’s forces were killed.

It is not known for certain why Villa chose to attack Columbus. The chaotic Mexican revolution had been causing death and destruction since 1910. By October 1915 the head of Mexico’s government, Venustiano Carranza, had not only beaten Villa but had been officially recognized by the U.S. as President of Mexico. It is possible that Villa was seeking revenge for what might be seen as an act of political betrayal (he had been, at times, friendly with the U.S.). It is possible that he was simply desperate for arms and stores to continue the fight. There are suggestions—still unproved—that Japan (allied since August 1914 with France, Russia and Britain in the European war) and Germany (engaged in bitter fighting against those four countries) were in some way involved because of their ongoing political machinations with Mexico.

The raid provoked a swift response. Major-General Frederick Funston, in command of the U.S. Southern Department, requested a military force, and within six days 6,000 soldiers under the command of Brigadier-General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing crossed into Mexico in pursuit (ultimately futile) of Villa.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

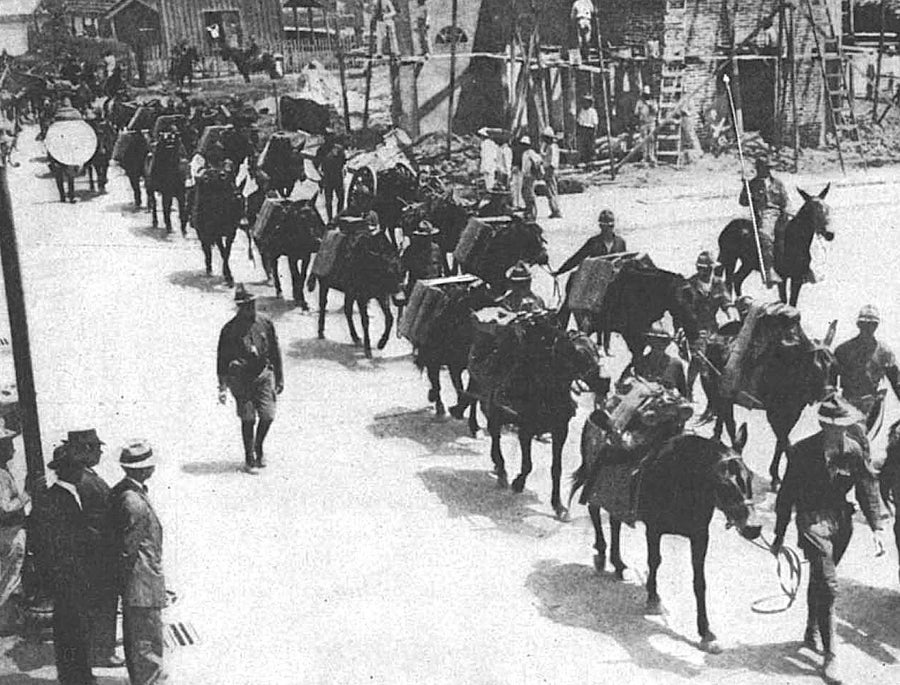

United States Army mountain gun battery. Such horse-drawn artillery was well suited for the expedition into Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa’s forces.

Image: Scientific American, March 25, 1916

In the article in Scientific American of March 25, 1916, there is speculation that Villa, desperate and out of options, had conducted the raid to provoke an invasion of Mexico, and that somehow he would be able to benefit from the ensuing U.S.–Mexico animosity.

The ability of Villa must be recognized. He is courageous, aggressive and resourceful. His whole career has shown that he is willing to take long chances and to run great risks. After our recognition of Carranza as the head of the de facto government of Mexico, Villa had little left but his life, and that was dependent upon his ability to keep ahead of his pursuers. Having nothing to lose, his only chance to win was to involve the American Government in his trouble and to trust to his luck to get some advantage out of it. Destruction of American property in Mexico, outrages committed against Americans in Mexico, isolated and sporadic raids over the border, brought no action from the American Government. Then came the organized and, in a way, official raid upon Columbus and the attack on American troops at that point. This raid has demanded official recognition and official action on our part. And up to this point, Villa has accomplished his purpose.

We have in the reciprocal arrangement with Carranza, a certain authorization to send our punitive expedition across the border in pursuit of Villa. As soon as this is fairly under way, it will be Villa's next move. It is fair to assume that he did not make the Columbus raid for the mere desire of being pursued both by the Carranzistas and by the Americans. Nor that he figured only that it was better to be shot by Funston's men than to face Carranza's firing squad.

The temper of the Mexican people is well known. Their attitude toward Americans has been unmistakable. It is not alone the organized brigands serving as Villa's army, nor the more numerous and better class of Carranzistas, who dislike the Americans, who are suspicious of every move we make, and who are ready for any action against the " gringoes." But the dislike for Americans affects practically all the Mexican people, except those whose business interests and connections lead them to favor the stability and security of American control.

Can Villa arouse the Mexican people to the point of general and united action? Should he do so, he has two grounds of hope. The first is to regain his lost popularity, to become the "liberatador," the idol of the oppressed people, fighting against a foreign invader. The other alternative would be to unite with Carranza, and probably Zapata, and restore the status quo of the opposition to Huerta, but this time directed against the Americans.

Villa had and has nothing to lose and everything to gain.

Carranza, on the other hand, has all to lose and nothing to gain by opposing the American policy.

Pancho Villa and his band of guerillas were pursued by the U.S. military for almost a year, but never caught. He remained on the run until July 1920 when he negotiated a peace settlement with the Mexican president at the time.

-

Our full archive of the war, called Scientific American Chronicles: World War I, has many articles from 1914–1918 on the U.S. viewpoint of the politics of the First World War. It is available for purchase at www.scientificamerican.com/products/world-war-i/