This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Reported in Scientific American, This Week in World War I: June 19, 1915

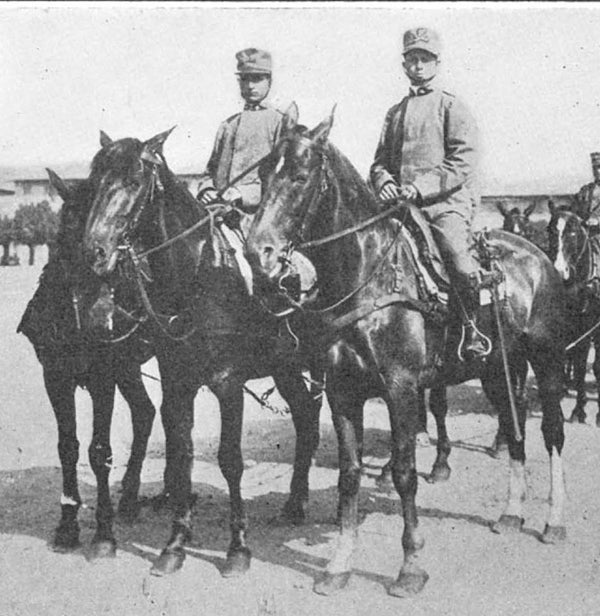

Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary on May 23, 1915. The great hope of the Allies was that an army of more than a million men would be thrown against the Austro-Hungarian troops guarding their southern flank at the northeast corner of Italy. The Italian army was described optimistically, with a couple of warning notes:

Italian horse-drawn field artillery. Highly mobile—on flat ground. Image: Scientific American, June 19, 1915

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“The new Italian army has yet to win its spurs under the severe ordeal of modern European fighting. A considerable number of first-line troops are veterans of the recent war against Turkey, but the bulk of the army has yet to receive its baptism of fire. So far as can be judged from press reports, Italy with its four armies of invasion, operating against Trent and Trieste, has been everywhere successful; but the crucial test will come when the Anstro-German armies are encountered in full force. There is reason to believe that the average quality of the Italian army is equal to that of any of the armies engaged in the present struggle. The Alpine troops have long been reckoned among the finest of the mountaineer soldiers of Europe.”

Expectations of the Italians were high. Yet according to this article elsewhere in the June 19 issue, the first couple of weeks of the Italian effort in the war seemed lackluster:

“So far the Italian invasion of Austrian territory has furnished us with nothing spectacular. This certainly is not due to lack of preparation by Italy, for she had ample time during the diplomatic negotiations preceding her entry into the war in which to complete all her arrangements for striking swiftly. Nor does it appear to be due to inactivity of the Italian army nor any serious opposition of the Austrian forces on the Italian frontier."

“Nature is the great ally of the Austrians in this theater of war and the Italians have encountered more opposition from her forces than from Austrian bullets. The Italian frontier was fixed by Austria to suit her own military ends. From Switzerland to the Adriatic Sea it follows the southern or Italian slopes of the numerous chains of the Alps. For many miles (in some places as much as three hundred) back of the frontier line on the Austrian side, one mountain chain succeeds another in a confused mass of precipitous heights and narrow valleys, with few good wagon roads and fewer railroads.”

The article accurately points out the difficulty of fighting in the spectacular, rugged, mountain terrain that was totally unsuited to the large-scale offensive attacks favored by the Italian military—especially given that the Austro-Hungarians held the high ground.

Italian troops manning a trench, 1915. The image probably shows a training exercise as opposed to front-line fighting. Image: Scientific American, June 19, 1915

Not addressed in either of these articles was the fact that although Italy’s scientific and technical capabilities could turn out excellent weapons, the industrial base was as yet too thin to mass-produce enough of them for the expanding army fighting the new kind of large-scale warfare.

Why did Italy enter the war? The articles do not—and in 1915 could not—make any mention of the machinations by Britain, France and Russia that had encouraged Italy’s entry into the war. These countries had all signed the secret Treaty of London in the month before Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary. The treaty seems like a straight bribe: Italy enters the war and in return is promised ownership or control of territories that in 1915 were held or administered by Austria-Hungary, Germany and Turkey—all countries that Italy expected to defeat in war. The Treaty of London, by the way, was exposed when copies of it were found and published by the Bolsheviks after the October Revolution in Russia in 1917. By then the Italian army had lost almost 700,000 dead, had suffered one of the largest defeats in the war, and was close to collapse.

-

Further Reading

Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms is a semi-fictionalized account of his work as an ambulance driver for the Italian army during the Great War.

A fine history on the Italian front considers the military, political and artistic aspects of the fierce fighting in the snowy Dolomite region: The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front 1915-1919, by Mark Thompson (Basic Books, 2009).

Our full archive of the war, called Scientific American Chronicles: World War I, has many articles from 1914–1918 on the chemical aspects of the war. It is available for purchase at www.ScientificAmerican.com/wwi