This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Since its discovery, electricity has helped humans make labor and tools more efficient. From lighting to toothbrushes, electricity has aided us in making our lives simpler and more convenient. However, while searching through the archives, I’ve come across some inventions that have led me to question whether we’ve taken advantage of technology in order to yield control.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

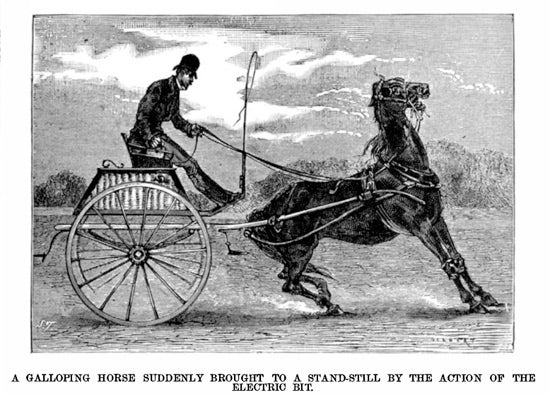

Take for example the electric horse bit invented by M. Defoy and featured in the December 27, 1879, Scientific American Supplement. The bit was connected to an electromagnetic apparatus by metal wires placed in the reins. The rider simply turned the crank of the electromagnet and a current of electricity was sent to the horse’s mouth, meant to startle the creature into passivity.

The invention was deemed successful after being used on several “vicious” and “stubborn” horses who, when resisting being shod, were given the shock and immediately submitted. According to a report by the Superintendent of the Parisian Cab Company, M. Camille, “One horse that was to be shod went so far as to lie down and roll over and over on the ground, all the while struggling, defending himself, and fighting against everything; nothing could subdue him. I then had recourse to M. Defoy’s apparatus, and, on the first trial, much to my surprise, the feet of the intractable horse were lifted without any great difficulty, and on the second trial it was as easy to shoe him as if he had never made the least resistance; the animal was conquered.”

It’s difficult to say whether this triumph of technology over nature should be celebrated or shunned. The article does state that the shock was not enough to benumb the horse (which seems obvious, as a benumbed horse would be of no use), but instead produced an uncomfortable astonishment and a pricking sensation “peculiar to electricity.” However, the “success” of the electric bit then led the same inventor to create an electric riding whip, adding even more discomfort to the horse.

Horses were a necessary part of 19th-century society, and the ability to control the animal was imperative in order to harness it for transportation and labor. While there were certainly other options for training, electricity provided a convenient (albeit uncomfortable) method that has apparently had enough popularity to still be used today—many pet owners use electric collars and fences to help train their four-legged companions. Still, the discomfort depicted on the horse’s face in the accompanying picture presses me to question the morality of using intentional pain (let’s be honest, electrical shocks hurt) to control an animal.

Clearly, not everyone agrees with using electricity to tame horses, and there is even a separate school of horse training known as “natural horsemanship” that aims to work with the animal’s instincts rather than against them. In the end, I wonder whether an invention like the electric horse bit speaks to our ingenuity or our laziness when the discipline of another being has been required.