This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

I’m sure you’ve all been to an airport and seen the moving walkways that look like flattened escalators. Some people take them as an excuse to not walk whereas others use them as an opportunity to speed up their walking time. Now, imagine this same concept in transportation perched a story off the ground on a busy city street, conveying pedestrians back and forth through the metropolis.

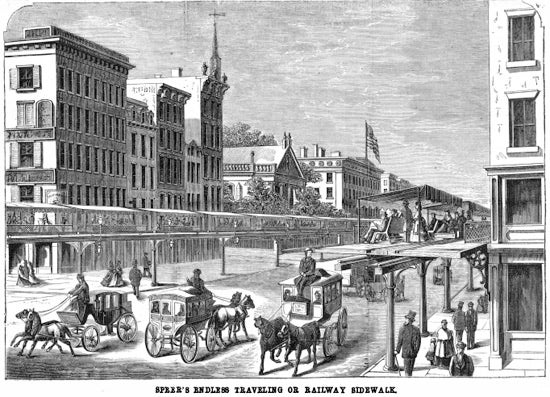

Scientific American featured a design of this nature by Alfred Speer of Passaic, New Jersey, in the April 20, 1872, issue called the “Endless Traveling" or "Railway Sidewalk.” The rail could have been used in any crowded city, but Speer envisioned it to be used in New York City on a busy thoroughfare like Broadway.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The movement of the sidewalk was produced by underground engines below ground. The sidewalk was to be held up by ornamental iron pillars (five to six per block) placed along its outer edge. This would help hide the motion of the rails from horses on the ground who may have otherwise been scared of the movement.

The elevated sidewalk itself was to be 16 to 18 feet wide and placed 12 feet away from the sides of buildings along the street. The owners could then choose to place a walkway from the first floor of their buildings to the sidewalk, driving more traffic into their ground floors. Otherwise, travelers were able to climb up to the sidewalk via stairs placed at street corners.

Pedestrians were able to get on and off the perpetually moving elevated sidewalk without interfering with the travel of fellow passengers. The sidewalk moved at a rate of 10 mph or faster, increasing the speed of the average pedestrian who, according to the article, walked at four mph. For those not wishing to walk, the sidewalk also offered chairs or settees for passengers.

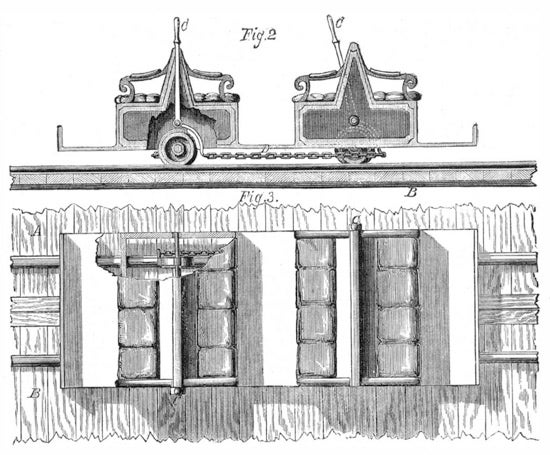

Figures 2 and 3 show the design of the moving sidewalk. B is a stationary rail while the rail at A moves at the same speed as the moveable sidewalk. Seats have two sets of wheels, one on the stationary rail and one on the moving rail.

“It is evident that should the wheels on the fixed rail be kept from moving, while the others are left free to rotate, the transfer seats will stand still. When so standing, passengers may step with perfect safety from the fixed platform into the moving seat. Now, if the wheels on the fixed rail be released, and those on the moving rail be kept from turning, the friction of the moving rail, on the wheels so held, will soon impart an advancing motion to the car or seat equal to the moving walk, at which time the passengers may step from the seat to the moving walk as safely as they stepped upon the platform of the seat.”

Mr. Speer believed that because of the perpetual motion of the platform, problems of overcrowding that existed in railway cars could be avoided. However, the project never got enough financial backing to get off the ground (pun intended).